Art has always offered new ways of seeing, providing glimpses into diverse worldviews and creating futures that we can strive to inhabit. On the evening of Feb. 7, the University Centre Ballroom saw a group of artists, students, and educators interrogating these multiform possibilities, recognizing the potential for art to be a reclamation of space, a form of liberation, a medicine, and an education. Indigenization and Art, an event hosted by the Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU) celebrated Indigenous artists and identities, casting the spotlight on Zoe Gesaset-Gloqowej Lee (Chinese-Mi’kmaq), Jenni Makahnouk (Anishinaabe), and Chelazon Leroux (Dene First Nation) to share their teachings and art with the McGill community.

The room was gently abustle with students, milling amongst a host of local Indigenous art vendors. Monalisa Simon (Inuk), owner of Oddly Monalisa Creations, designs cute, concealable self-defence tools for women, responding to the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit People across Canada and the U.S.. While the crisis demands systemic change rather than placing responsibility on individuals to protect themselves, Simon responds with practical creativity, imbuing self-defence with elements of individuality and empowerment. A table nearby summoned a large crowd with their bucket of soapstone, encouraging guests to try carving. People sat on the floor, hands busy as they chatted amicably with representatives from Atelier Tlachiuak, a grassroots collective of Indigenous artists, the majority of whom are Inuit, in Tiohtià:ke. The collective provided space for unhoused artists and promoted “art’s power to heal, unite, and drive social change.”

The night would not be complete without its speakers, interviewed by Raymond Jordan Johnson-Brown (Arts, U3)—a social media personality, and Gender, Sexuality, Feminist and Social Justice Studies (GSFS) student at McGill. Institutions “work for Indigenous communities but not often with them,” Johnson-Brown remarked. He saw this gathering as an opportunity for further dialogue and collaboration between Indigenous and settler folks, facilitated by art.

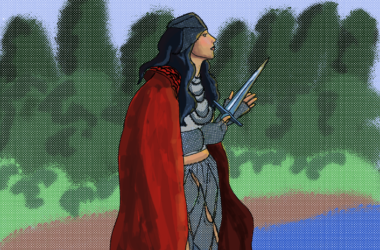

On McGill’s campus, where many of the night’s contributors do not see themselves or their communities reflected, art can operate as a potent method to reclaim space through visibility, serving as an assertion of presence, permanence, and continuity. For Lee, designer, muralist, and McGill undergraduate student, her artwork—in this case, a mural intended for the SSMU lobby—is a recognition of Indigenous presence within the McGill community. Lee’s practice investigates legacy and self-recognition, blending influences from the people she loves and the aesthetics which inspire her such as Pinterest art and risograph printing. The mural will depict “traditional medicines from across the country” such as sweetgrass, cedar, and Saskatoon berries.

The second speaker was Jenni Makahnouk, an Anishinaabekwe beader and McGill’s first Anishinaabekwe valedictorian. Makahnouk critiqued the institution’s emphasis on French and English languages, stating she feels represented by neither. She seeks to uplift Ojibwe and other Algonquin languages, using beading as a methodology to explore the ties between language and craft. For Makahnouk, beading is both an artistic and educational practice—one that resists colonial linguistic structures while fostering cultural healing. She reminds the audience that “Indigenous art is still art,” deserving recognition as “luxury goods” rather than pigeonholed as simple handicrafts.

The grand finale of the evening was carried out by the dazzling Chelazon Leroux: Drag artist, comedian, and educator. Leroux views drag as a means of storytelling, humour, and healing—integral practices for many Indigenous communities. Raised in Treaty 8 Territory, Fond Du Lac First Nation, they describe drag as a “superhero” persona that helped them navigate intergenerational trauma and explore their Two-Spirit identity, which they describe as being “the blessing of carrying both the feminine and masculine spirits.” When explaining that many Indigenous worldviews are defined by one’s role in supporting their community, Leroux said that being Two-Spirit is a responsibility to bridge the genders, providing a third way to serve the community. Leroux closed the night with a vivacious performance, their shimmering hair flashing as they danced to Doechii. The evening highlighted art’s power to reclaim space, challenge institutionalized erasure, and foster connection—affirming Indigenous presence and creativity as integral to the McGill community.

Zoe Gesaset-Gloqowej Lee is a Design Editor at The Tribune. Though quoted, she was not involved in the editing or publication of this article.