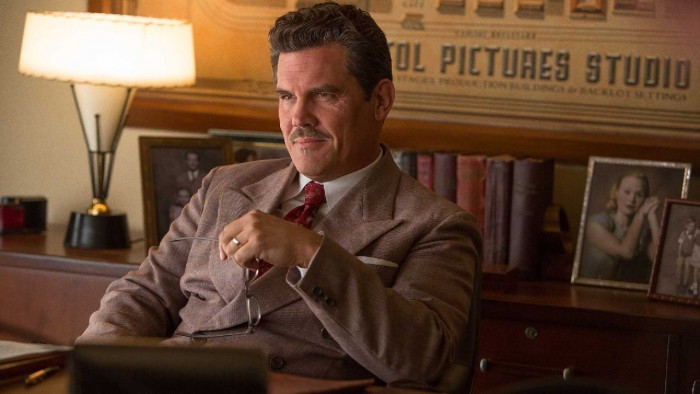

It makes sense for directors to pay homage to their industry as a whole. An entertaining romp through the Hollywood of the 1950s, Hail, Caesar! is the Coen brothers’ latest triumph, an in depth study of a single man, Eddie Mannix (Josh Brolin), a studio fixer, who works tirelessly to keep the massive machinery of Capitol Productions in motion.

Though it is clear that Mannix’s life is anything but calm, the plot is truly set in motion when studio star Baird Whitlock (George Clooney) is kidnapped by a group that elusively calls itself ‘The Future.’ The film accompanies Mannix as he attempts to fulfill the requirements of Whitlock’s ransom, determine whether to take an offer at a more lucrative and ordinary job, and quit smoking for the sake of his wife, Mrs. Mannix (Alison Pill).

The film is a testament to the Hollywood of the past, but works quite differently than a film like Hugo (2011). It highlights the artistic aspects of Hollywood, but is based more on the business side of showbiz. Although the 1950s was a period of uncertainty for the film industry, owing to the rise of television, in Hail, Caesar! many of the tropes of glamorous old Hollywood appear to be intact. Gossip columnists lie in wait for the newest scandal, and stars push against their public images.

At the beginning of the film, Mr. Mannix assembles various religious men to discuss the script for the film-within-a-film Hail, Ceasar!, starring Whitlock, a vice-driven and innocuous Hollywood superstar. In this meeting the Coen brothers display their penchant for awkward humour as men of different faiths debate the importance of Jesus. This scene lays the essential foundation for the film’s thematic focus on religion. It also serves to lull the audience into believing that ‘religion’ will be understood in the most traditional sense of the word; however, as the parallel experiences of film weave together, it is clear that the real ‘religion’ is not Mannix’s Catholicism, but the unifying experience of movies themselves.

The conflict between cramped and epic spaces reflects Mannix’s experience of his faith(s). In his rapid, sure-footed movement between the cramped quarters of a confessional, the coziness of a Chinese restaurant, to the grandeur of Capitol studios, he transitions between his own inner conflicts. Rather than being consumed by the largeness of Hollywood, Mannix’s presence expands to fill this space. In contrast to Mannix’s constant race against time, the Coen Brothers are leisurely in their pace. The flow from one location to the next is marked by seamless camera movement from intimate close-ups to wide displays of the inner-workings of the studios themselves. In such a way, the direction takes the time to savour the various aspects of 1950s Hollywood in ways that Mannix rarely pauses to do so himself.

The effect of the almost laborious attention to setting the scene, however, is to diminish the sense of urgency for the fate of Whitlock. The various ambitions of the film—an spoof of/homage to old Hollywood, a comment on one man, his faith, and free will, an ode to the power of cinema—at times feels forced and so reduces the storytelling strength of the film. In the various themes that are addressed, the plot is at risk of becoming secondary to the stories within the story.

Perhaps in a gesture to their own role in creating the film, the most interesting characters are the directors. While DeeAnna Moran (Scarlett Johansson) and Hobie Doyle (Alden Ehrenreich)—two of the stars under Mannix’s charge—are respectively glamourous and humble, they seem more interested in enjoying their time off screen than on it. By contrast, Laurence Laurentz (Ralph Fiennes), an English director, claims that his film, Merrily We Dance, will be the next piece in his great legacy. Garbed in an ascot and three-piece suit, he comes not only from another country (he is above all else English) but from another period.

The audience is reminded of their own role in watching the film. The multiplicity of screens, from Mr. Mannix’s private viewing room to the debut of major motion pictures, brings the screen itself into focus. The curtains are drawn, the opening credits roll, and the enthrallment begins. Though one is never entirely drawn into the films-within-the-film, as the scenes often cut to the reactions of Mr. Mannix and his secretary, Natalie (Heather Goldenhersh), it is clear that the art lies not in the film itself but in the experience it elicits.