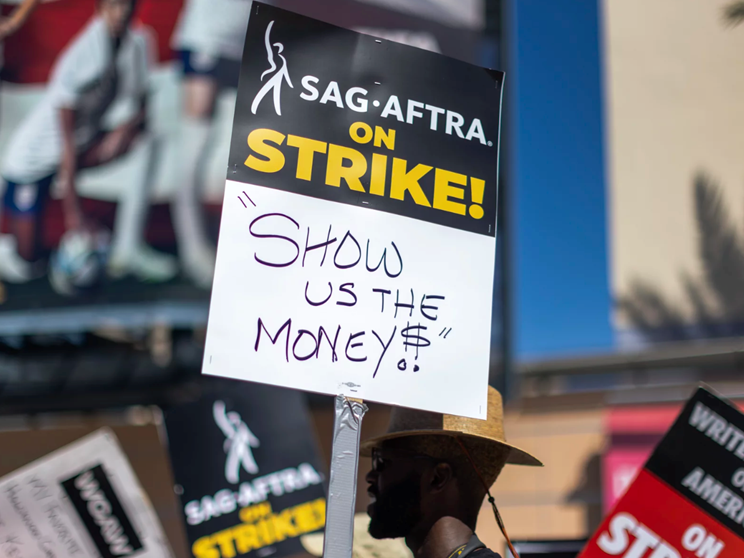

On July 13th, the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) and the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA) voted to strike after unsuccessful contract negotiations with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). The next day, SAG-AFTRA joined the Writers Guild of America (WGA) on picket lines across the United States, marking their first joint protest since 1960.

The AMPTP represents multi-billion-dollar production studios such as HBO, Disney, Netflix, Sony, Amazon, and Apple. Despite these companies’ overwhelming wealth, a staggering 87 per cent of SAG-AFTRA members earn under $26,470, making them unable to qualify for union health insurance. Meanwhile, Disney CEO Bob Iger dismissed SAG-AFTRA’s demands as “unrealistic”—a deeply ironic statement from a man who makes $31 million annually. These workers’ rights issues are not isolated to the entertainment industry, further justifying the broader need for this strike.

SAG-AFTRA is fighting for fair compensation in the era of streaming platforms and, now, artificial intelligence (AI). Out of SAG-AFTRA’s 86 proposals, key demands include increases in general wages, updated employer contributions to health and retirement plans, and better residual payments. The AMPTP’s inadequate counter-offers revealed more-than-mild disagreements on those core subjects. SAG-AFTRA seeks higher wages because their previous contract with the AMPTP failed to support actors through high inflation. The union also claims that the AMPTP’s response toward raising employer contribution caps for health and pension plans—which haven’t changed in 40 years—was “insufficient.”

Unsurprisingly, the growing threat of AI exacerbates these issues. If left unregulated, AI will quickly jeopardize the livelihoods of all actors. Background actors in particular face an immediate risk because their digital likeness would eliminate the need for studios to hire extras by using and reusing the actors’ image on other projects.

Other than regular salary shortcomings, actors and writers are fighting to change how studios disburse residual paychecks. Residuals were determined by a formula—which writers and actors established the first time they struck together—and reflect the number of times a production is played and replayed on a cable network or sold as a DVD copy. Streaming services operate very differently, and top media executives have capitalized on these discrepancies for over a decade. Consequently, residuals have decreased dramatically, going from tens of thousands of dollars to cents.

Recently, the story of Alex O’Keefe, a writer for The Bear, went viral because he could not afford to buy the suit in which he accepted his WGA Award for Best Comedy Series—and such occurrences affect actors, as well. Recurring cast members of Orange Is The New Black—a show credited for Netflix’s ascendancy in TV and film—said they were paid the union minimum and kept their day jobs while working on the multi-award-winning series. If the artists behind critically acclaimed shows cannot make a living, then it’s not hard to envision the predicament of the myriad of artists working on smaller-scale, independent projects. Since the public has found these concerns to be valid, reasonable, and universal, support was strong in the strike’s early days. Now, as the writers’ strike approaches the five-month mark and the actors’ begin its second, the economic impact of this decision—albeit a necessary one—is becoming clearer. Other than 39 indie projects (which SAG-AFTRA authorized as they are being produced by non-struck companies),commercials, and reality television shows, union members cannot partake in any on or off-screen work, auditions, or promotional activities. So, much of the entertainment industry is on hold for the foreseeable future. It’s understandably difficult to imagine the world’s most beloved A-list actors struggling to make ends meet after months of unemployment, and for good reason: They aren’t. For too long, production studios have exploited working-class actors to make their already rich executives even richer. In an unprecedented time, these artists have the upper hand. And it’s the perfect occasion to support the 160,000 striking actors fighting for the future of performing arts.