For as long as humans have looked to the stars, we have wondered what lies beyond the scope of our stratosphere. This wonder particularly piqued the imagination of artists and writers in Soviet Russia. On Feb. 20, a crowd gathered in the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) to hear Asif Siddiqi discuss this cosmic enthusiasm in Bolshevik Russia. Siddiqi, a history professor at Fordham University, painted a picture of a 1920s Soviet Union (USSR) enraptured by the concept of galactic travel.

The talk was a part of the CCA’s lecture series, Search for a New World. The series explores Russian sci-fi throughout the 20th century, focussing particularly on how the genre was influenced by existing technology and inspired many to think about utopianism and new societal organization. The series is a counterpart to the CCA’s exhibition Building a new New World: Amerikanizm in Russian Architecture, which considers Russia’s relationship to modernity and the United States though its architecture.

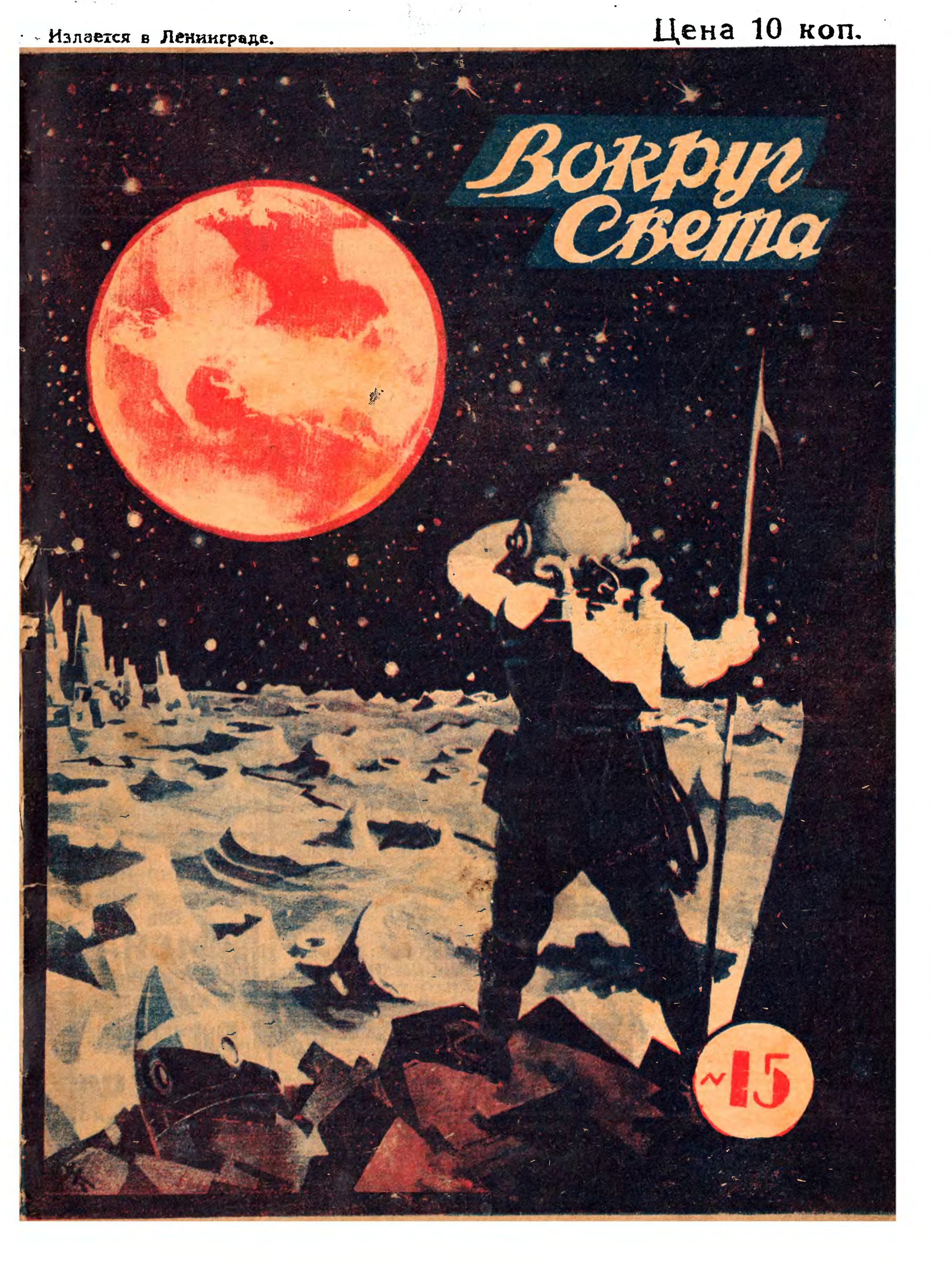

From literature, to modern art, and films, the endless possibilities of the cosmos inspired creatives and captivated the general public. Space travel offered a chance for the USSR to carve out its place in space and history, symbolizing the seemingly endless limits of human invention and exploration in the age of modernity.

North American audiences are most likely familiar with the USSR’s major role in the 1960s space race, though the countries advancements in space travel were the result of more than just a simple competition. Siddiqi explained that, starting in 1917, Russian popular culture drastically shifted its attention towards the heavens, inspired by Soviet utopianism and the Marxist fascination with technology. The ‘space fad’ of the 1920s was a massive phenomenon that pervaded all aspects of culture, and Siddiqi’s research traced the theme of the cosmic throughout fiction, film and art, along with the public’s reception.

To show the pervasiveness of the sci-fi genre, Siddiqi noted that one-fifth of all books published at the time were science-related. Siddiqi pointed to Alexei Tolstoy’s Aelita as an example of Bolshevik-era science fiction. The successful novel follows a young man who travels to Mars and starts a proletariat uprising against the planet’s elite. Its adaptation was the first Russian sci-fi movie, a silent film, sold out theatres on opening night in 1924—extremely rare for the time. In the world of contemporary art, Kazimir Malevich and Boris Ender experimented with abstract and geometric styles to represent imaginary space stations and theoretical concepts like infinity.

“[These artists believed that] art should mirror technological advancements, mechanically and abstractly,” Siddiqi said. “They were crafting a universe without a reference point.”

Not only were creatives producing copious amounts of space content, but the public loved every minute of it. Lectures on space travel were so popular that police were frequently called to quell the massive mobs attempting to push their way into the auditoriums. Before there were “Trekkies” and “Whovians,” there were Russian space enthusiasts making up their own intergalactic languages and space names. Space clubs hosted exhibitions that featured rocket models and hypothetical maps of Mars. One exhibition showcased a blueprint for a rocket that would melt its own wings to provide fuel for the engine, to which Siqqidi commented that we certainly haven’t reached that level of technological advancement yet. Later on in the 1930s, the popular preoccupation with space travel died down and shifted towards the more realistic aspiration of aviation, but the Soviet Union continued to produce sci-fi works beyond the initial craze.

Search for a new New world continues on March 5 with Sergei Kapterev on Soviet Sci-Fi Cinema of the 1950s–1960s. The exhibition Building a new New World runs until April 5 at the Canadian Centre for Architecture.