In the spring of 1962, a 15-year-old boy named David Jones was admitted to a London hospital with an injured left eye. The young Jones had apparently been involved in a scrap with a close friend over a girl. The fight left the boy’s pupil permanently dilated, a condition that would last for the rest of his life. It was not the first time that David Bowie was different. It certainly would not be the last.

Bowie died this past Sunday, Jan. 10 following an 18-month battle with cancer. Like countless others, David Bowie coloured my life. I can remember playing “Life on Mars?” on repeat until I fell asleep, or speeding through the Florida everglades to “Young Americans” on family vacations. For those who grew up on his music, Bowie meant freedom. He told us that it was okay to change, even if you didn’t always know what you were changing into. He told us to be ourselves, but didn’t place any limitations on what ‘ourselves’ could mean.

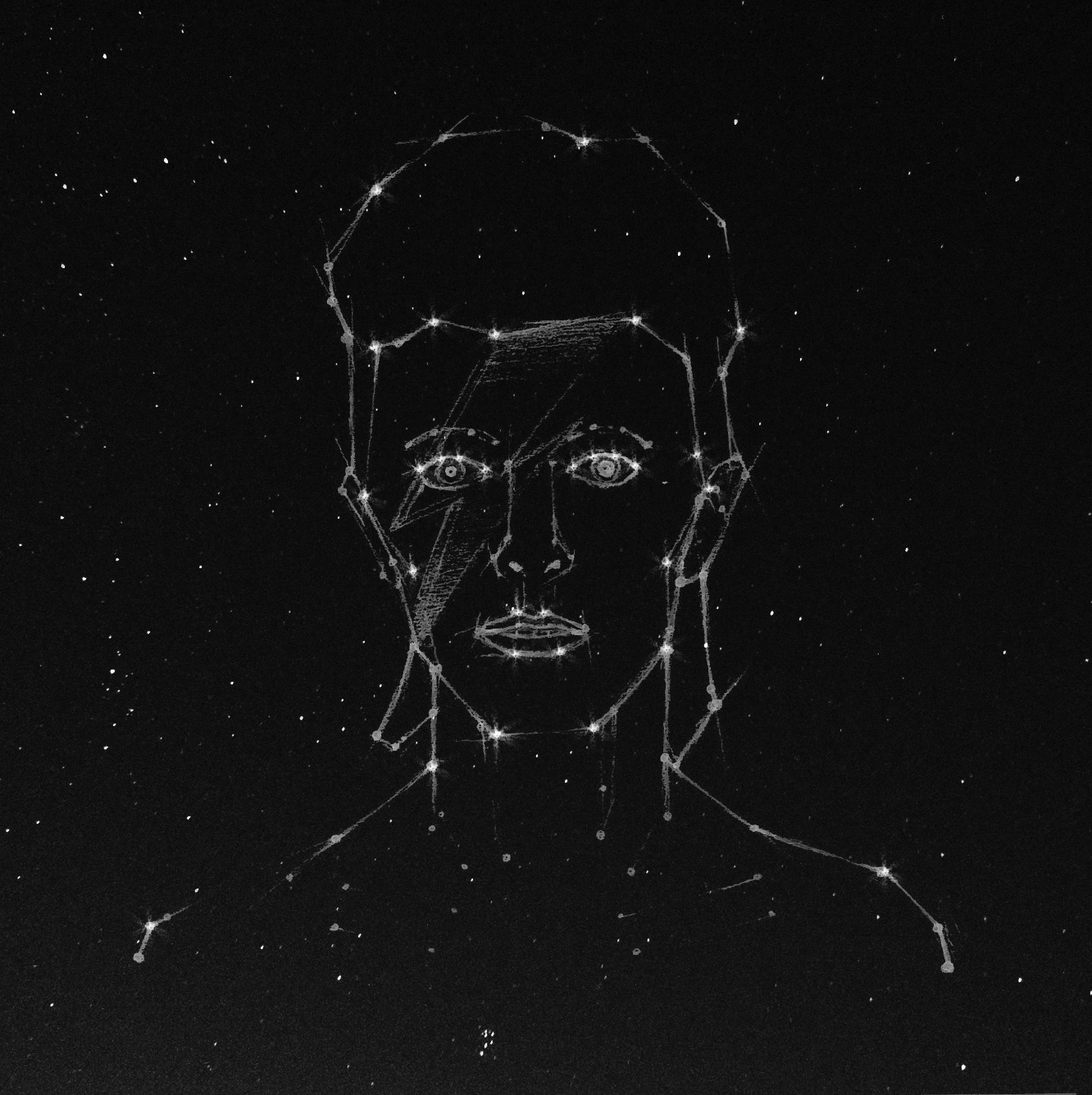

For an individual of his scope, cancer almost feels underwhelming. Bowie felt immortal. He sent his characters to untimely and dramatic deaths, only to emerge like the biblical Lazarus in a new, always interesting persona. His death is so jarring in part because he hardly existed in the traditional sense. Bowie was a musician, actor, fashion icon, and performance artist; a true colossus of the arts. More than this, he was a concept, an alien from outer space, a mythical figure here to save us from the mundanity of our everyday lives. He was a challenge to contemporary ideas of masculinity and sexuality, as well as a vessel for cultural reflection. To imagine him going to the grocery store, enjoying a leisurely stroll, or dying like the rest of us feels preposterous. After all, he claimed in a Rolling Stone interview to possess “a repulsive need to be something more than human.”

But David Bowie was human. Despite his many fabrications and identities, Bowie was, above all, a romantic. You can see it on the cover of Ziggy Stardust (1972), where a lonely alien stands on a wet and desolate street corner. Perhaps Young Americans (1975) is an even better illustration; a backlit Bowie sits hunched over behind a lit cigarette, the beginnings of a smile forming on his face. But above everything, you can hear the romance. You can hear it in the wistful opening chords of “Starman,” the unfiltered snarl of “Rebel Rebel,” the jubilation of “Modern Love,” and the infamous “WHAM BAM THANK YOU MA’AM” of “Suffragette City.” You can hear it louder still in the delirious melodrama of “Life on Mars?” or the catharsis of “Heroes,” his ultimate ballad. His songs were a matter of life and death, at once sweetly melodic and packed to the rafters with political and emotional dynamite. At times, it felt like it might fall apart at any moment. The beauty of Bowie, and indeed of rock ‘n’ roll, was that it never did.

Bowie’s characters may have been artificial, but the emotion in his songs never felt contrived. He could pretend to be an alien, a soul singer, or a German Krautrock musician, but there was always something in his music that sounded decidedly like Bowie and nobody else. He was a performer, and perhaps a fake, but he was never artificial. Maybe Bowie never felt like one of us, but he could connect to us in a profound, distinctly human way. I think that paradox is part of what makes his music, and music in general, great. It’s certainly why the life and work of David Bowie will continue to be enjoyed for generations to come. It’s written in the stars.