When I was little and my parents were checking out at the grocery aisle, I would wander over to the greeting cards and wait. It was only upon discovering the floral-fronted sympathy cards that I began to realize death was all around us. With a history as banal as its subject matter, death is the unknowable reality of our everyday lives. It is one of the few universal experiences we all share and yet our relationship to it is anything but simple. In navigating loss, we often ask: What is there to be said when words fail?

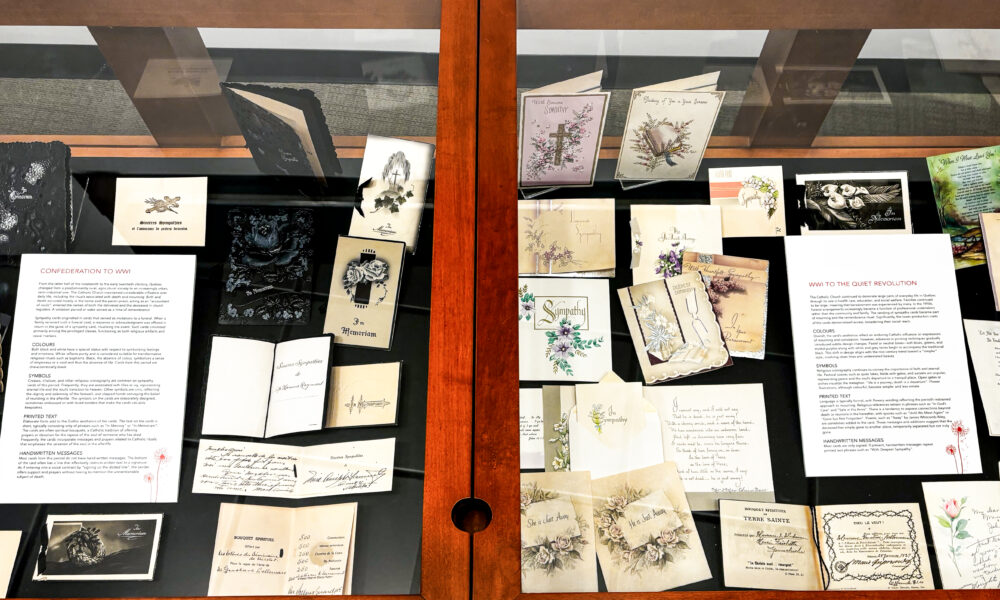

Hosted in the Osler Library of the History of Medicine until Apr. 1 and curated by the Maude Abbott Medical Museum of the Pathology Society, When There Are No Words explores the shifting sociocultural attitude towards grief through a collection of uniquely Québécois sympathy cards. The exhibit examines evolving perspectives across four primary chronological periods—Confederation to World War 1, World War I to the Quiet Revolution, the Quiet Revolution to the end of the millennium and contemporary times—tracing Quebec’s transition from a predominantly French Catholic society to an increasingly secular, multicultural one through our popular understanding of loss.

Originating out of necessity, in a time when letters were the primary means of remote communication, sympathy cards were initially responses to funeral invitations and simple tokens to not yet provide support but rather acknowledge grief in a time where there are no words. Often featuring black motifs and restrained text, the cards offered support without having to mention the effectively unmentionable topics of death directly, exercising sensitive restraint and respect through euphemism. Through depictions of angels and written phrases such as “pray for us and the souls of purgatory,” the cards from this era reflect the Catholic overtones that dominated society, filtering into every aspect of life—even death.

From World War I through the Quiet Revolution, an “enlightened” perspective on death emerged. Sympathy cards from this period embraced minimalist pastel palettes and imagery intertwining religion and nature—gardens, gates—reframing death as a journey rather than a final departure. Handwritten cards added a personal touch but mostly echoed printed text, reinforcing tradition over individuality.

The Quiet Revolution marked one of Quebec’s most profound cultural shifts, particularly in its ever-growing detachment from Catholicism. As Quebec secularized, skepticism of the Church grew. With rising resentment, home wakes declined, and sympathy cards shifted from funeral invitations to secular expressions of empathy. By the end of the millennium, sympathy cards had begun to trade out religious aspects for themes of nature and individualist spirituality.

With an understanding shaped by recent scientific advancements, death is increasingly interpreted through the contemporary lens as a medical phenomenon. Sympathy cards can come from healthcare and ICU workers, reaching out to patients and their families. With personalized handwritten messages and cursive fonts mimicking the intimacy of handwriting, these cards reflect the highly individualized nature of loss. The collection’s inclusion of many more English cards than in earlier periods also reflects the changing demographics of Quebec.

In this time, we begin to reevaluate our understanding of loss, particularly the nonlinear, decentralized grief which affects not just family members but everyone who was close to the deceased. When a husband dies he leaves his wife a widow, but what is there to be said about the silently bereaved—such as the mourning of miscarriages, stillbirths, pets, ex-partners, or the passing of friends and coworkers? When society fails to acknowledge grief, is it made any less real?

“There is a poem by Kenneth Patchen,” said Rick Fraser, Director of the Maude Abbott Medical Museum in an interview with The Tribune. “‘There are so many little dyings that it doesn’t matter which of them is death.’ I think he was expressing that we lose things all the time. There are little deaths and there are big deaths and we must pay attention to each of them because they are all a part of our lives.”

An exhibit that captures the quiet weight of grief, When There Are No Words gives voice to what words often fail to express. Quebec’s sympathy cards are not relics of the past—they are privileged living artifacts that evolve alongside us. They portray Québécois sympathy in its most intimate form. As the exhibit reminds us all—sometimes it really is the thought that counts.

When There Are No Words is on view at the Osler Library until Mar. 30.