It began as your typical run-of-the-mill wintery sore throat. The slightly inflamed tonsils, scratchy throat, and minor shivers did not prove worthy of a lengthy emergency room wait, much less a painfully early morning, cued up in the cold to snag an appointment slot at the McGill clinic. But a couple of days of home remedies including Halls, fluids, and multivitamins failed to ward off the storm brewing in my brain. As pain increased and the sensation of thick skin amassed from the bottom of my nose to the top of my collarbone, the inability to distinguish my chin from my face or neck pushed me out the door towards the nearest hospital, Hôtel-Dieu.

As the Canadian healthcare algorithm goes, the more serious the issue, the shorter the wait time. I waited only a few minutes between my examination by the triage nurse and my meeting with the emergency room doctor. Taking a look at my throat, he spewed out a multitude of causes for the colony of lymph nodes protruding before him, comically casting my throat as “Nothing like I’ve ever seen in my 25 years of work!” and inviting all residents over to take a look at my freakishly swollen face and neck.

My first impressions of the hospital were nothing but positive. Clean, accommodating, friendly and efficient— what more could one ask for in such a vulnerable physical state? I was attended to by pleasant health care professionals, each assuring me that I would be able to fully open my mouth sometime soon, that this vial of blood should be the last, and that the intravenous would do its job.

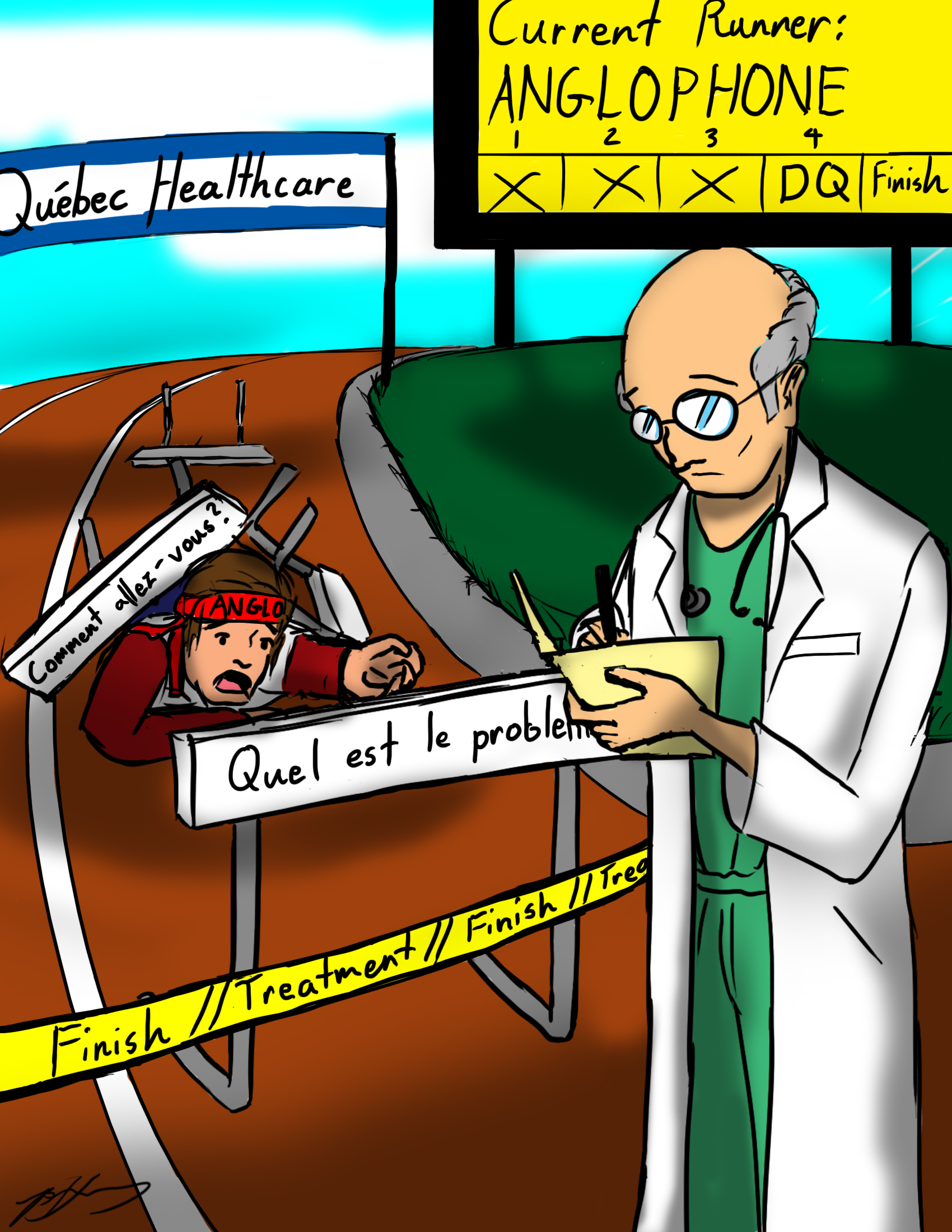

However, an inability to pinpoint the infection that plagued me extended my stay at the hospital from Friday evening to Sunday afternoon. While the prolonged visit allowed me to emerge from the hospital healthier and with a heavy dose of antibiotics flowing through my veins, it also became the first time I felt the weight of discrimination.

At first, everything was going fine, until my English-accommodating roster bequeathed to their homes for a rest in between shifts. When dealing with them, the doctors, nurses, and I would meet each other half way with broken versions of French and English to come to an understanding. One nurse even sought out another co-worker to do my blood work because of her inability to communicate with me.

But the new night nurse assigned to me, unlike her co-workers, made no effort to accommodate to our language discrepancy. Whenever I asked her a question, she would reply to me in French. Then, informing her that I could not understand what she was saying and requesting English, she replied, “Yeah, I can, but you speak too fast.” Aside from the illogical nature of responding to someone in a different language as a punishment for his or her apparent speediness when talking, keep in mind that the swelling of my throat forced me to utter only a couple of words at a time, stretching my mouth as open as possible to annunciate words without igniting too much discomfort.

Ten minutes after I asked to have a caretaker that I could communicate with, I was removed from my single room, which was directly across from the nurse’s station, to the back corner of a narrow hallway right in front of a door. As the nurse stormed away from our heated attempt at trying to speak to one another, I assumed her frustrations would be eased by a break or a breath of fresh air—not by forcing me out of my room altogether. When the hospital staff pushed my bed to its new location, she sarcastically waved and smiled goodbye to me.

One would assume that the snobbery elicited from using the English language in a typically French area would be limited to places such as restaurants, clothing stores, and government offices—in other words, places where clear communication could not mean the difference between life and death. My tumultuous encounter with the nurse had given me a new perspective of language discrimination for Anglophones in Quebec. I wanted answers.

It began with a quest for stories similar to mine. Telling my hospital-gone-bad story to friends and fellow students, tales ranged from one student recalling a time he hopped in a cab to get to the closest hospital, Hôtel-Dieu, and a cab driver warning him that, although it was further, driving the extra mile to the Royal Victoria Hospital would be much better, considering his lack of French.

Most other students interviewed attended Royal Victoria Hospital instead as well, regardless of its distance from their homes. As one student put it, “I feel more comfortable [at Royal Victoria] because I know it’s associated with the school, so I just assume there will be English speakers there.

Although the search for a first-hand account similar to my own yielded returns in which most students talked about intense wait times, further research proves that language discrimination in Montreal hospitals is significant in the field of medical ethics today.

“Dialogue McGill,” a two-day conference held this March to explore communication issues in Canada’s health care system addressed the question of language minorities—especially those who speak English—in Quebec. Keynote speaker Antonia Maioni, associate professor of the department of political science, stressed the strong relationship between health care and politics, emphasizing that changes in the greater Canadian political climate are bound to spill over and affect health care services, noting that “these language questions don’t exist in a vacuum.” She pointed out that in order to fully understand the complexities of protecting minorities in public services, such as health care, broadening the lens of analysis to account for the country as a whole is essential for understanding.

Specifically, Maioni believes the current federal government’s lack of special interest in social policy, combined with its tendency to stay out of provincial matters cultivates a “phantom federalism” in which the government will only pop up into matters as needed. This, mixed with the Parti-Québécois’ focus on keeping provincial doors tightly closed, and Canada out of Quebec’s health care, jeopardizes the protection of minority rights in a publicly funded service. In essence, this lack of leadership on the part of the federal government, Maioni believes, has a high impact on minorities. Despite health care services being a provincial matter, the country’s commitment to spending so much public money on providing health care services insinuates the promise of an equitable service; if all persons are expected to shell out cash for a service, they must have equal rights, and equal services.

In an effort to confront the challenges of providing equitable health care, health care professionals and researchers in the field are seeking to implement innovative strategies to accommodate for the fact that, upon arriving to Canada, 42 per cent of immigrants speak neither English nor French.

Preliminary findings in research conducted by Eric Jarvis, Rana Ahmed, Andrew G. Ryder, and Laurence Kirmayer presented at Dialogue McGill suggest that language discrepancies in the Quebec health care system have a lasting impact: patients are less likely to return for additional care, or follow-up appointments if they speak a minority language. Considering this, the discoveries suggest that, although health care in Quebec and Canada is fundamentally a publicly provided service, only a portion of the population feels comfortable reaping the benefits.

While the statistics may cast a negative shadow over Canada’s already scrutinized health care system, practical solutions can be put in place to lessen the impact for minority language speakers in Quebec. Jarvis et. al suggest employing different avenues for professional interpreters to make themselves available on-site for clinicians and patients.

Similarly, inducting new language teaching materials for nurses to boost confidence and efficiency in communicating in second or third languages will pave way for a clearer exchange. Elizabeth Gatbonton and Leif French of Concordia University, and University of Quebec at Chicoutimi respectively, call for a greater focus on garnering confident language abilities for nurses today, noting that in an already highly-sensitive communicative sphere, providing nurses with practical language tools will increase effectiveness in patient to clinician relationships.

So despite living in a French-speaking place, you haven’t learned the language but you expect everyone to speak English fluently, and you have no patience for their difficulties, but you accuse them of discriminating against you? How very arrogant.