The Arctic is a place of unfound possibilities and potential opportunities, to the point that five countries have laid claim to much of the region. In fact, these disputes are serious enough that politicians have advocated for increased military presence to enforce their sovereignty in the Arctic.

Whether or not this military advocacy is legitimate or just political rhetoric is debatable, but the wealth of the Arctic and the ambitious intentions of these countries are far from fictional.

In December 2013, Canada made preliminary plans to redefine its borders in the Arctic region. However, the drive toward making claims in the Arctic has not always been at the forefront of Canada’s initiatives.

Canada’s Arctic represents 40 per cent of all the nation’s landmass, an area of 3,921,739 square kilometres—large enough for France to fit inside it six times. It is a vast region comprised of tundra, large mountains, and very little vegetation. Across all this land, however, there are just slightly more than 100,000 inhabitants. To the unobservant eye, the Arctic is a cold, barren place with minimal potential.

Other nations, on the other hand, have been relatively successful in using the Arctic to their advantage. Russia and Norway, for example, produce 20 per cent of their respective GDPs from their Arctic regions.

While opportunities in the Arctic exist, the Canadian government has so far failed to capitalize on them.

Michael Byers, a professor of political science at University of British Columbia and a McGill alum, noted the difference in development in the Arctic by various countries.

“Relatively speaking, the Canadian Arctic is the least developed of all the Arctic regions,” Byers said.

In recent years, the arctic has become a hot topic for politicians and the media. Prior to his election as prime minister in 2006, Stephen Harper made the Arctic one of his top campaign priorities—considering specifically the issue of Canada’s arctic sovereignty.

“The single most important duty of the federal government is to protect and defend our national sovereignty,” Harper said in a speech in 2005.

Harper argued for the need for increased military presence to uphold Canada’s claim—meaning more troops and a larger navy. While the idea appears favourable and patriotic, few Canadians actually know about arctic sovereignty, what the government is doing in the North, or why it even matters. In fact, arctic sovereignty stretches far beyond the idea of security, delving into even more controversial issues of economic development, the environment, and Indigenous matters. Upon closer inspection, the opportunities and challenges within these areas are massive, and has the potential to be highly rewarding.

What is Arctic sovereignty?

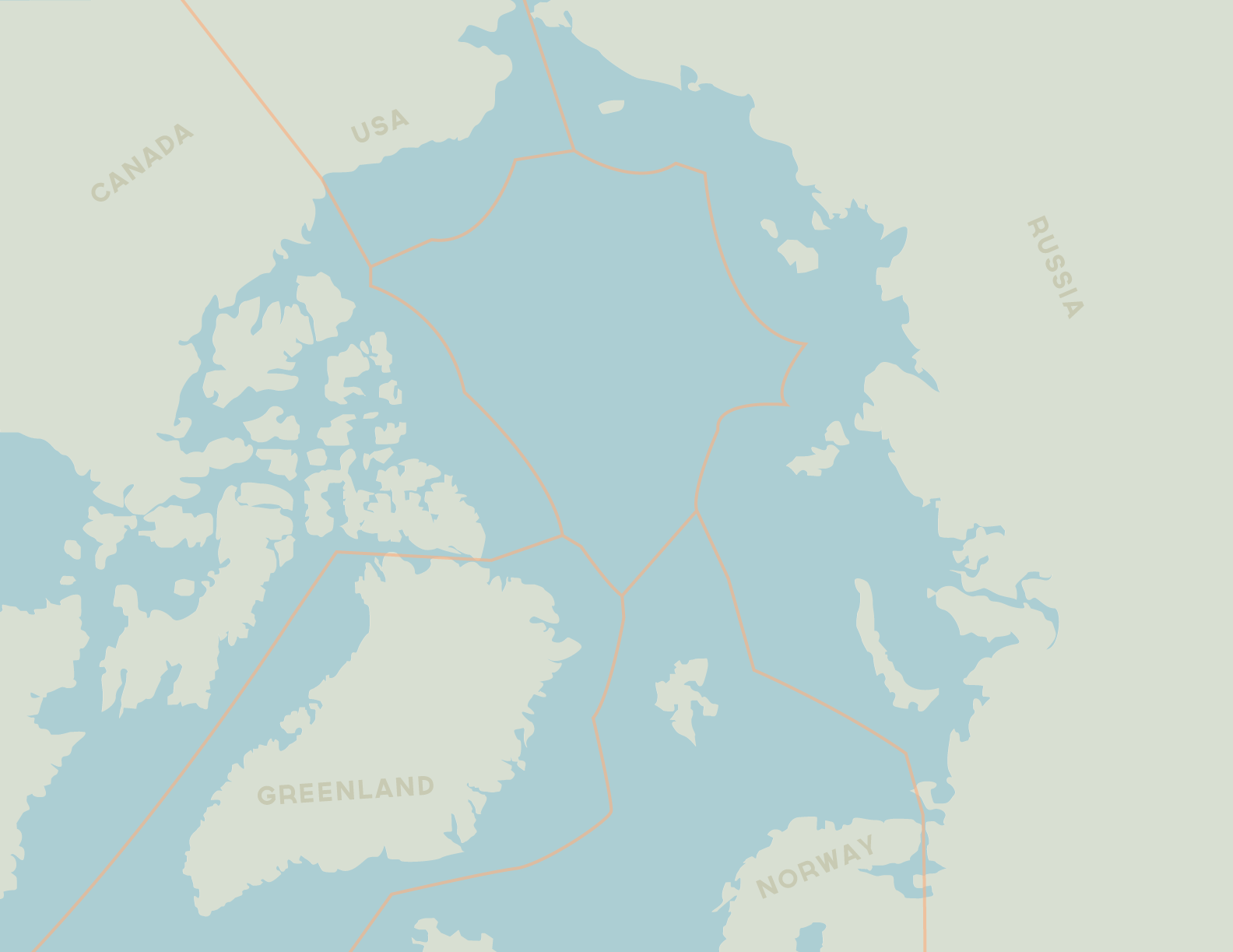

The term Arctic sovereignty describes claims made by Arctic states on waters beyond the state’s land borders as being their own. The Arctic region contains seven countries—Canada, Russia, Denmark (Greenland), Sweden, Iceland, Norway, and the United States. While no country has sole possession over the North Pole or the Arctic Ocean, each one—except for Iceland and Sweden—asserts that parts of the waters and islands are within their borders. In order to lay claim to an extended continental shelf, which ranges past a country’s exclusive economic zone 200 nautical miles beyond the country’s land borders, a country must ratify the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which defines the rights and responsibilities of nations in their use of the world’s oceans. In addition, the law also establishes guidelines for scientific research in the ocean, the environment and the management of natural resources. Once ratified, a nation has 10 years to file its submission.

In 2003, Canada ratified UNCLOS, and on Dec. 9, 2013, Canada submitted its preliminary information that defined where the continental shelf lies. However, Canada must continue extensive scientific research to accurately determine where these boundaries extend. Once this has been settled, the UN will review the analysis further to make the final call, and country-to-country negotiations will be required. This could take several decades.

Sovereignty realities

Within its claim, Canada estimates that its extended shelf area spans 1.2 million square kilometres in the Northern Atlantic Ocean—a survey of the Arctic Ocean has not yet been completed. The fact that not all of Canada’s scientific data has been completed could create problems for its extended shelf claims by potentially conflicting with those made by the United States and Denmark. These situations are resolved primarily through diplomatic negotiations between foreign affairs ministries. For instance, in 2012 Canada settled an agreement with Denmark regarding a dispute north of Ellesmere Island and Greenland.

However, according to Byers, who has written extensively on arctic sovereignty, the reality is that Canada’s sovereignty disputes are minimal.

“Canada only has three arctic sovereignty disputes,” Byers explained. “One over a tiny island that is only 1.3 square kilometres; one over an area of seabed over the Beaufort Sea; and a third over the extent of Canada’s regulatory powers in the Northwest Passage—waters that [almost] every other country accepts [to be] Canadian.”

The only other country to dispute Canada’s control over the Northwest Passage is the United States, which claims that the body is an international strait. This disagreement will continue until either a diplomatic agreement is made, or an international court settles the matter. So far, neither has taken place.

In addition, politicians and the media often predict an essential arms race taking place between the Arctic states in order to enforce their military presence. According to Byers, Canada has done almost nothing to increase its Arctic security.

“There are only 200 Canadian forces personnel based in the Arctic on ongoing basis at Yellowknife,” Byers said. “The prime minister has promised to build Arctic patrol ships for the navy, but no construction contract has been signed seven years after the promise was made. He also, seven years ago, promised a naval port in the Arctic, but again, nothing has happened there.”

However, Byers noted that military presence does not equate to being involved with the challenges and opportunities of the Arctic.

Economic Potentials

Part of why claiming vast amounts of cold, barren land has become a major priority is because of the huge economic potentials that exist within the north. According to the United States Geological Survey, the Arctic contains over 20 per cent of the world’s undiscovered petroleum resources, including oil, natural gas, and natural gas resources. 84 per cent of these resources are offshore, and potentially in disputed regions.

According to Byers, investing in large infrastructure projects, such as ports, roads, and alternative energy are other significant ways to extract the economic potential of the Arctic.

“We need to recognize that there are economic opportunities that don’t simply involve digging things out of the ground,” Byers said. “There are vast opportunities in terms of alternative energy. Most people don’t realize this, but the highest [cliffs] in the world are on Baffin Island, [Nunavut. There is] enormous potential for tidal power, for wind power in Canada’s north.”

According to Leona Aglukkaq, minister of the environment, minister of the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency and minister for the Arctic Council, the current federal government has taken drastic steps to increase economic activity in the North.

“Our government introduced in 2006 a Northern Strategy,” Aglukkaq said. “For the very first time, there [are] policy initiatives of the federal government focused on developing the North in four pillars, and that is around responsible resource development, devolving governance, sovereignty, [and] economic development.”

The Northern Strategy, which is designed to meet the challenges and opportunities of the north, according to the program’s website, has led to the development of two mines in Nunavut alone since 2007.

Aglukkaq also explained how sustainable economic policies have been developed through the Arctic Council—an intergovernmental organization with members from each of the Arctic states with the intention of addressing issues facing the Arctic through shared knowledge. In one example, Norway shared information with Canada on how to construct windmills that could sustain cold temperatures of the Arctic climate. Canada is the current chair of the council. During its chairmanship, Canada implemented the Arctic Economic Council, which seeks to promote sustainable business development in the Arctic and encourage cooperation with the people living there.

Environmental issues

While the economic potential may be tempting, increased development of the Arctic could possibly lead to future environmental issues. Currently, the Arctic is affected by climate change more than almost any other region on the planet. The Arctic Ocean, for example, once completely frozen solid, now sees ice-free summers.

“I think that in the late summer, an ice-free Arctic Ocean is now inevitable, just because of the momentum that climate change has in terms of emissions that have already occurred,” Byers said.

Climate change, as well as increased economic development, has had dramatic effects on biodiversity within the Arctic—including damage to fish, vegetation, and mammals. This could have a dramatic effect on the Indigenous peoples in the Arctic, many of whom rely on the wildlife in their livelihoods.

Finally, as the mining of natural resources increases, the threat of potential toxic chemical spills becomes more pertinent. These spills could have negative impacts on the health of both wildlife and people.

According to Aglukkaq, the Arctic Council recently implemented policy to address the threat of chemical spills. The Agreement on Cooperation on Maritime Oil Polution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic—which was adopted in 2013—seeks to increase cooperation and coordination of the Arctic states on oil pollution preparedness and response in the Arctic in order to protect the marine environment from oil pollution.

However, critics have questioned the effectiveness of the proposal. According to Christy Ferguson, Arctic project leader for Greenpeace Canada, the agreement is far too vague, and would do little to prevent an oil disaster.

“The agreement does nothing to protect the Arctic environment and nothing to protect the peoples of the Arctic … It is effectively useless,” Ferguson told the Globe and Mail.

Indigenous relations

Various Indigenous peoples of Canada’s North, primarily the Inuit, comprise over 50 per cent of Canada’s Arctic region’s population. Therefore, cooperation between the Indigenous peoples and the federal government is vital to endorse Arctic sovereignty and regional development.

In 2008, the Inuit living in four of the Arctic states signed a Circumpolar Inuit Declaration on Sovereignty in the Arctic, which defines the parameters of sovereignty and its potential effects on the Inuit.

“The actions of Arctic peoples and states, the interactions between them, and the conduct of international relations must give primary respect to the need for global environmental security, the need for peaceful resolution of disputes, and the inextricable linkages between issues of sovereignty and sovereign rights in the Arctic and issues of self-determination,” the declaration reads.

According to Chester Reimer, a senior policy analyst for the Inuit Circumpolar Council, the Inuit are supportive of the sovereignty claims put forward by the Arctic states. However, they want to ensure that they receive benefits of their exploits of the Arctic, since it is their home and has been so for centuries.

The Inuit live in four different regions within Canada, called land-claim settlement regions. Within each region, the Inuit have laid out their own interests in sovereignty and economic development.

“[For example,] The Nunavut [Land Claims] Agreement gives Inuit [peoples] a certain amount of control over offshore resources, offshore matters,” Reimer explained. “So Inuit [peoples] would argue to the extent that Canada is extending its boundaries, then the Inuit of that area should also claim their rights and responsibilities as stipulated in their land claim settlement agreements.”

However, the Inuit have yet to experience many of the benefits that the Arctic could bring. According to Byers, the government has failed to give the Inuit an opportunity to thrive.

“The Inuit have been let down badly by successive federal governments in terms of health and education and housing,” Byers said. “The blame for that rests with successive federal governments. It will cost many billions of dollars to turn that situation around. I think that’s necessary and important, but I don’t see the political will.”

Canada‘s Arctic future

According to Byers, it seems impossible for any future Canadian government to avoid addressing Canada’s claims in the Arctic due to the potential economic and environmental issues that have so far been left unacknowledged.

“Whether a different future government would do more, I think [the answer] is yes, only because the very rapid changes in the Arctic caused by climate change—the melting of the sea ice, the melting of the permafrost, the increase in shipping—all demand more action by government,” Byers said. “So I don’t think future governments will really have a choice. I think that the Harper government may be the last government that can get away with doing almost nothing.”

According to Aglukkaq, the Arctic is ready to meet its full potential and increase its economic activity. All the region needs is the interest and curiosity of Canadians in the south.

“The Arctic is the last frontier of Canada,” Aglukkaq said. “It is a region that has been ignored for far too long, and up here, we want development; we want development on our terms and conditions, [and] we have the processes in place [to do so.]”