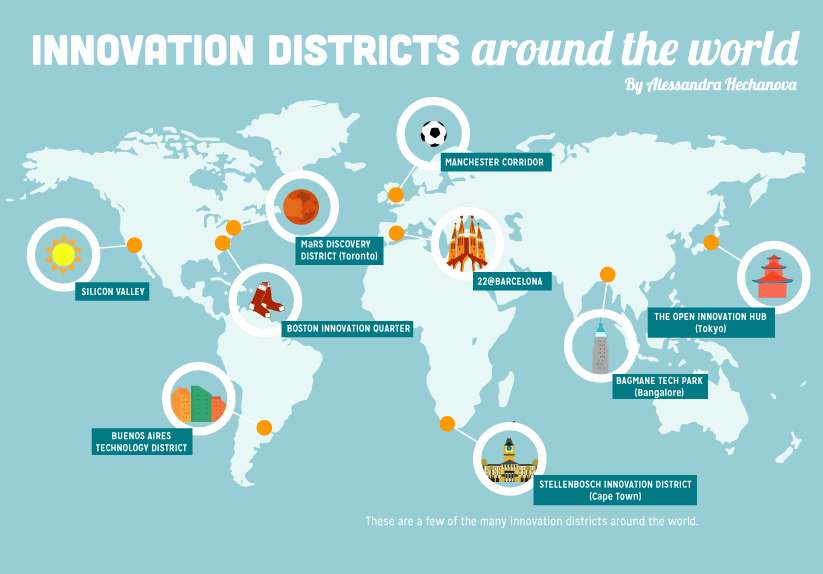

While the Quartier de l’innovation (QI) has generated considerable interest since its announcement in January 2012, the concept of the innovation district is far from new. From Silicon Valley to 22@Barcelona, cities and governments today are investing billions of dollars in urban redevelopment projects that bring people and businesses together into one physical location.

What many don’t realize is that fostering innovation through physical proximity is not a new concept to Montreal. In 1998, the Quebec government launched a development project in an old industrial area just across the highway from the QI’s location in Griffintown. Called the Cité du multimédia, the venture was initially proposed as a way to facilitate collaboration in Montreal’s growing multimedia sector. However, it has since faced criticism for turning the district into a mere extension of the downtown’s corporate offices.

So where exactly did this demand for innovation districts come from? And why do some fail, while others succeed?

The history of the innovation district:

While creating better solutions and products has been a recurring industrial goal throughout history, the foundation of physical districts to do so is a much more recent phenomenon.

According to Richard Shearmur, a professor from McGill’s School of Urban Planning, a policy emphasis on “innovation” has evolved over the last 30 years, after developing countries began producing large-scale, cheap goods for western markets in the ‘70s.

“How do you unblock saturated markets to get western people to carry on consuming? By innovating, by finding new things for them to spend their money on,” Shearmur said. “If you emphasize actually trying to produce better products than developing countries, that’s a way of maintaining your [economic] position.”

In the ‘80s, sociologists began to observe that some of the most successful industrial areas throughout history were locations that facilitated collaboration between many small, specialized companies.

“[For example], a lot of gun makers were in a district in [19th century] Birmingham,” Shearmur said. “You had the barrel manufacturers, the firing-pin manufacturers—they were all different companies but they came together to make guns. And their guns were particularly good because there was a lot of knowledge and a lot of specialization.”

This same concept has since expanded beyond manufacturers to encompass all types of innovation and entrepreneurship—from technology and science to cultural and urban development.

“The idea is if you have a group of economic agents who are grouped together geographically, and provided that there is a culture of openness and exchange, these geographic districts will lead to innovative solutions because there’s a lot of information exchange [and] a lot of collaboration between people,” Shearmur said.

McGill and the Quartier de L’innovation:

The QI follows this concept of developing a geographical space that encourages innovation, using an area in Southwest Montreal that includes Griffintown, Pointe Saint-Charles, Saint-Henri, and Petite Bourgogne. Launched in May 2013, the QI is led by both McGill and L’École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS), an engineering school located in the area.

“If you look at different universities in the U.S. or even in Europe, you see that [they] are engaging more and more with their communities,” McGill QI Project Director Isabelle Péan said. “For McGill, the objective is really to develop a hub—a living lab—where students can get specific experience [and] develop specific projects.”

The initial stage of the QI was funded in 2012 by several stakeholders: the government of Quebec, the Economic Development Agency of Canada, and the City of Montreal contributed $350,000 each, while ÉTS and McGill contributed $370,000 each.

According to Péan, once this money has been used, the QI will be driven by a non-profit organization that will find funding for its projects, and which will be overseen by the QI’s Board of Directors.

“We want the QI to be led by the community, by people involved with the project,” she said.

Part of this community involvement will come from students, according to Justin Leung, U1 Arts student and member of both the McGill QI Student Working Group and the McGill QI Steering Committee.

“There are incubators, entrepreneurial hubs, [and] start-up houses all over the world, and they’re all trying to recruit the best students,” he said. “We’re trying to build a project with McGill [from] the start, and then provide those resources to the students who need help or need the support.”

Less than one year after the project’s official launch, there has not been a substantial amount of change in the district. However, that may not be surprising given the nature of the project, according to McGill Director of Internal Communications Doug Sweet.

“MaRS [Discovery District in Toronto] has been around since the beginning of the 2000s and it has taken them a decade to get bigger, draw more funding, and produce more projects,” Sweet said. “[The QI is] like a garden being cultivated right now, and more seeds will be planted. [Nothing] has grown up yet because it’s too early.”

Branding, the Cité du Multimédia, and gentrification:

Though the QI is a relatively new project, it is not the first urban redevelopment venture in Montreal to aim to foster innovation and collaboration.

The Cité du multimédia from 1998 aimed to create a central location for the city’s multimedia sector to create jobs and revitalize the Faubourg des Récollets district. The project involved demolishing some of the old industrial buildings in the neighbourhood and constructing new office buildings, which were rented out with salary subsidies for newly created jobs.

However, 15 years later, the Cité du multimédia has faced criticism for failing to realize the goal that the project initially promoted. Due to factors such as expensive rent and conditions on leases, the anticipated small multimedia companies and start-ups never moved into the space, which was instead filled by larger companies.

Shearmur called the Cité du multimédia project an “abuse of branding.”

“[The government] used this branding to get the community on board [and] to get people to accept that they were going to knock down old buildings [and] kick out artists, because [they were] going to have this creative industry in place,” he said. “The Cité du multimédia basically turned out to be an empty slogan for redeveloping a neighbourhood.”

According to Péan, the QI is different from the Cité de multimédia due to the diversity of its stakeholders.

“The idea to bring people from the multimedia sector in one place with tax credits is not so bad,” she said. “But the problem is that if you do nothing to bring different kinds of partners (i.e. not only industry, but academics and people from the community) and try to connect people, no interesting interactions and collaborations will happen.”

However, Claire Poitras, director of the Urbanisation Culture Société Research Centre of the National Institute for Scientific Research, said the problem of branding persists in modern urban redevelopment projects like the QI.

“If you want to attract people to a specific place nowadays, you have to […] brand an area with a specific identity because people are going to move to a place that has special features, that is a distinctive place,” she said. “You have to sell the area as you would be selling a product.”

Instead of branding urban areas, Poitras said public decision makers should encourage ways for people to learn more about the urban history of areas—for example, through heritage tours. Otherwise, a brand could lead to harmful consequences, such as gentrification.

“We saw that in SoHo [New York] about 30 to 40 years ago,” she said. “Artists were attracted to it because it was cheap. Once they were there, other people wanted to be there as well, [but] gentrification occurred and the artists had to leave.”

Although other urban redevelopment projects have been criticized for gentrification, Sweet said the QI’s emphasis on urban planning sets the program apart.

“Urban planning is not part of MaRS at all; they’re not there to develop the neighbourhood—they’re there to develop business,” he said. “[The QI is about] trying to improve and help people stay [where they are], and not get forced out by gentrification as has happened in other neighbourhoods.”

For example, one QI project is to create a “laboratory of urban culture” in St. Joseph Church. Instead of allowing the land to be demolished and developed with condominiums, this project aims to repurpose the historic building as a space to preserve and encourage the artistic and cultural communities.

However, former McGill student senator Matthew Crawford, who voiced concerns about gentrification when the QI was announced in 2012, said he still believes the project will have negative effects on affordable housing in the area.

“Neither McGill nor the City of Montreal has demonstrated that it will move forward with this project with the necessary level of planning to make the project socially sustainable,” he said. “There are those who laud gentrification for its ability to rejuvenate neighbourhoods, [but] if the poor are simply swept away to the outskirts, then the process is not truly a rejuvenation, but an attempt to hide the problem.”

According to Poitras, the QI’s impact on the community will depend on how its various stakeholders interact.

“If there’s a good conversation between these types of actors, it should be fine,” she said. “They have to be sensitive to certain social demands they might have from community groups of the area. Some people might not want things to change that much.”

An outdated concept?:

Although innovation districts like Silicon Valley have received considerable attention for their successes, the technological advances of the last decade have led some sceptics to question their relevance.

“All of the observers up to the 1990s were functioning in an era where, if you were going to collaborate closely with people, you did probably need to be quite close to them because telephone calls were expensive,” Shearmur said.

The proliferation of the Internet, however, has changed the way businesses communicate.

“It’s far more straightforward and easy now for collaborations to occur which have nothing to do with geography,” he said. “So this fact that you actually need to be close together geographically to have these meaningful collaborations to lead to innovation—is that an idea [that] is decreasingly relevant today?”

However, Péan emphasized the continued importance of physical proximity in innovation districts such as the QI.

“Physical proximity is really important; […] crucial interactions are still face-to-face,” she said. “[With] two major universities engaged in developing concrete projects in technological, social and cultural innovation with their students and professors, it really becomes an attractive space. We need a critical mass for people to interact.”

The future of the QI:

Less than a year after its launch, the QI is still in the early phases of development. Despite the uncertainty of the changing way innovation occurs, Péan said the QI could help redefine the innovation district and its place in the city.

“At the QI, we want to develop entrepreneurship of course […] but we are also here to help non-profit organizations, to bring our students within those non-profit organizations, [and] to create links between the community and the university,” she said.

One way of fostering these links is through student engagement. According to Leung, the most important way for the QI to move forward is for students to contribute to discussions that aim to create more opportunities for involvement in the QI by joining groups such as the Student Working Group.

“We want to get the ball rolling,” Leung said. “We want students to know what the project is, [and] we want more and more students who are passionate about the project to join us.”

One goal for student involvement in the QI is through internships. According to Péan, 16 students were placed in internships or research programs relating to the QI in 2013, including four internships in urban planning and five internships in social enterprises.

However, others have expressed dissatisfaction with the way students will be able to engage in the district.

“Structurally, the QI involves applied learning facilities in close proximity to corporate partners,” Crawford said. “By placing ‘resources’ and ‘products’ closer to their ‘buyers,’ McGill emulates the structure of an industry, rather than an institution of education. In doing so, they serve private interests before the public needs of the city.”

Because the Internet now facilitates so much communication, Shearmur said the QI could be more effective if it serves less as an innovation district, and more as a way of showcasing innovative urban planning and social practices.

“These are lines that are quite different from the traditional view of the innovation district as a group of firms, companies, actors, who, through their social connections, are leading to innovation,” he said. “We’ve got to be careful that the Quartier de l’innovation is looking forward and not looking back at these ideas.”

As the district develops, Péan said only time will tell what will come from the QI.

“We really want to increase collaborations and partnerships with local partners in order to create opportunities for enriching our students experience and be engaged as a university,” Péan said. “The project is new, but I’m confident that we will have concrete outcomes in the next few years.”