86-year-old Betty McCullough watched the televised celebrations of Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee this summer and thought back to one of her fondest memories as a student at McGill’s graduate school for nursing. At 25 years old, she’d clutched her camera as she waited amongst a crowd of students, staff, and faculty who had packed McGill’s campus for a glimpse of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Phillip in their visit to the university during their tour of Montreal in October 1951.

Her pictures of that day, Betty says proudly, are as good as any published in the newspaper or yearbook. But her black-and-white photographs of the royal couple are not the only fond memories she has of her time as a student in Montreal. As Betty opens her 1952 Old McGill yearbook, she reminisces about how different life was as a student of McGill in the 1950s.

“A motorcycle […] another; an expectant murmur passed along the crowd […] The shimmering, sky-blue limousine passed through the gates and moved slowly up the drive.” This excerpt from the 1952 yearbook shows how students chose to describe the royal visit on Oct. 30, 1951, just three months before Princess Elizabeth ascended the British throne.

Weeks of hard work prepared McGill for the royal visit. On the big day, banners, flags, and crests lined the campus, brightening the scene with McGill’s official red and white and MacDonald campus’ green and gold. The students who lined the campus were dressed in their traditional scarlet blazers, while faculty members greeted the royal couple in full academic dress.

According to the yearbook, an estimated 10,000 people lined the streets of McGill’s campus in order to catch a glimpse of the royal couple.

Elizabeth and Phillip entered the Arts Building to meet with top university officials and student leaders, view mementos of previous royal visits, and sign the convocation register. They were also presented with two specially printed copies of that day’s issue of the McGill Daily before leaving campus to continue their tour of Montreal and the rest of Canada.

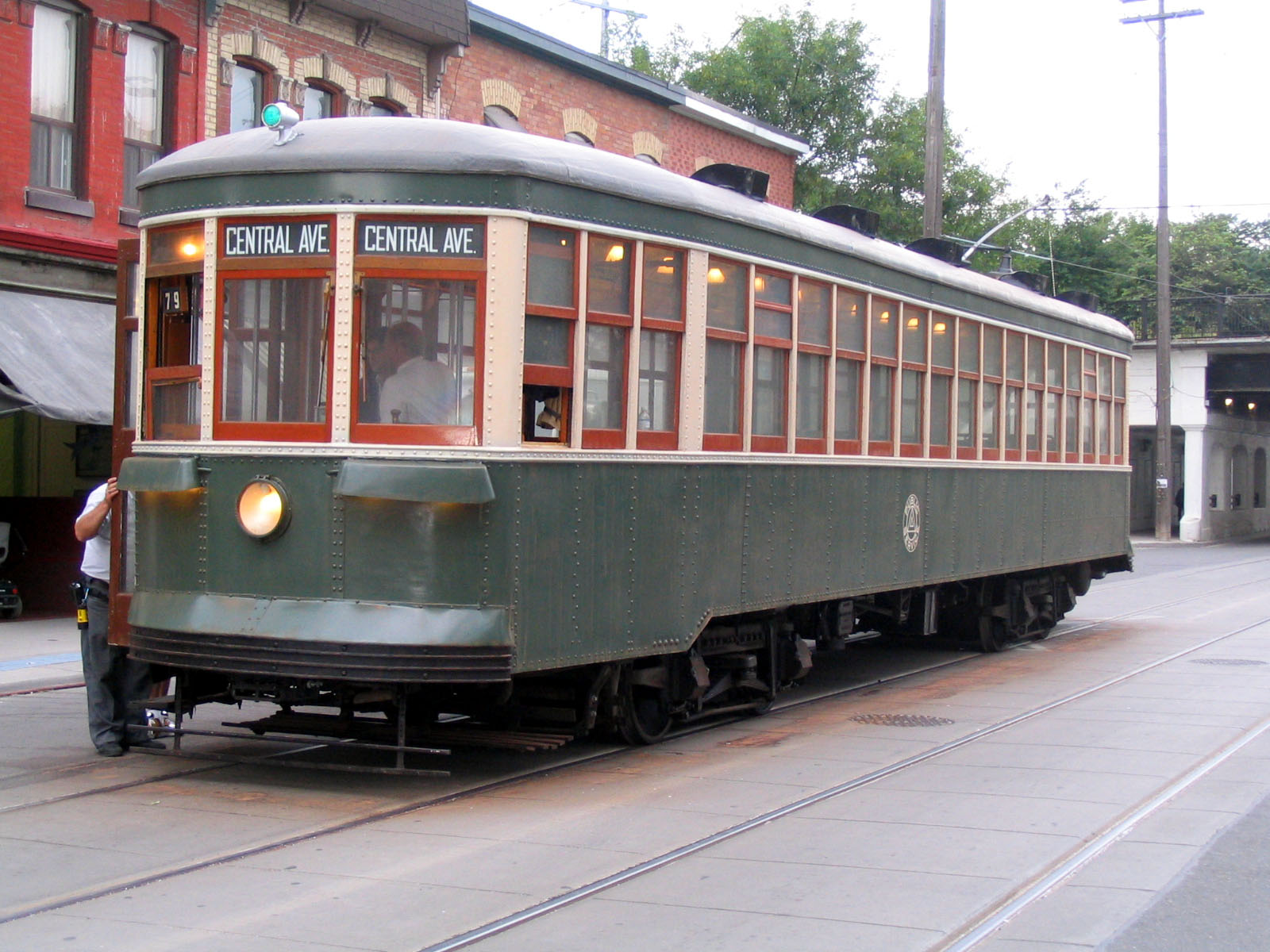

When Betty attended McGill, she lived in the town of Mont-Royal with her cousin. Living almost an hour’s commute away from campus wasn’t easy though, and Betty had to make use of the Montreal streetcar system to get to the university each day.

“It was quite a commute, you know, the old 65 [streetcar] going up the hill,” she says.

Other students had less orthodox methods of getting to school. One grandmother of a current McGill undergraduate student, declined to give her name but is known as ‘Nana,’ remembers her experience well.

“We used to hitchhike down everyday. Honest to goodness; we had the regular people who took us to school, the same people who went to work every day,” Nana says. “On the way back I rode the bus or streetcar.”

In the 1950s, Montreal’s extensive streetcar system was known as one of the most innovative in North America. The electrically powered streetcars featured a new pay-as-you-enter system, which meant that conductors no longer had to walk up and down the cars collecting fares—which had allowed some people to ride for free when cars were crowded. Pay as you enter was later adopted worldwide and remains in place in the majority of transport systems today.

As the 1950s progressed, however, Montreal’s public transit system underwent important changes. Later in the decade, the Montreal Transit Corporation started introducing buses to the city, since streetcars required more employees than buses and were harder to maintain during harsh Montreal winters. By 1959, all Montreal streetcar lines had been converted into equivalent bus routes. The metro system was not inaugurated until 1966.

Principal Frank Cyril James and the battle for university funding

Principal Frank Cyril James and the battle for university funding

While the amount students are expected to pay in tuition has changed significantly since the 1950s, Betty recalls that finding the money to foot the bill was just as difficult for many students then as it is now.

“Even in those days, when tuition was two hundred and some dollars, it was hard to come by,” she says. To pay the bills, she babysat her cousin’s two young children, and received free room and board in exchange.

Tuition has always been linked to university funding. One of the most valuable developments in McGill’s funding history was Principal Frank Cyril James’ successful lobby for federal funding for Canadian universities, like McGill, during his time in office from 1939-62.

For roughly the first century of its existence, McGill received only a small, token sum from government sources. This financial situation changed slightly in 1939, when McGill was promised additional financing from the Quebec government, but only a fraction of that sum was ever paid to McGill.

Following the outbreak of World War II, this statute was replaced by special wartime federal grants to universities, which took effect in 1951 and provided the full promised amount to McGill. After the war, federal funding offset the cost of the sudden influx of students by assisting universities that accommodated war veterans. With the looming prospect of additional costs in the wake of these grants, however, projections for McGill foresaw difficulty financing the growing university.

As both principal of McGill and chairman of the finance committee of the National Conference of Canadian Universities, the lack of federal aid was of paramount concern for James. In 1949, James met with then-Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent to urge the federal government to give aid to all Canadian universities.

The resulting Massey Commission found that Canadian universities, while growing to become an integral part of career training, were indeed facing a financial barrier that limited their ability to fulfill the needs of the nation. The federal government quickly accepted its proposal to pay each university a grant worth 50 cents to provinces per capita.

This federal agreement of 1952 would have a significant impact on university-government relations in the future, as it placed McGill on the same level as other Canadian universities, and provided, for the first time, an annual grant that was based on standardized regulations.

The building used at McGill for administration was renamed the F. Cyril James Administration Building in his honour following his death in 1973.

Looking at the map of McGill on the front cover of her yearbook, Betty remarks about how “foreign” the modern campus seems to her. In fact, only 28 per cent of the named buildings on McGill’s downtown campus were built prior to 1960. With the appearance of new buildings like Leacock, Otto Maass and the McLennan Library in the 1960s, the campus underwent a dramatic change in response to a growing need to accommodate more students.

“I don’t think it’s the same school at all,” Nana says, comparing her McGill to that of her grandchildren, “It’s so big. It’s like comparing a college to a university [in terms of size]—although it had been a university at the time.”

The 1950s were a period of growth for McGill, as the university received an influx of students that would permanently expand the student body. More students were attracted to universities because of a growing recognition of the institutions’ ability to prepare students for the working world. In addition, the Veterans’ Charter of 1944 allowed the many soldiers returning from World War II to receive free university education.

For McGill and other Canadian universities, these factors would have an enormous effect. In 1946, McGill had almost 8,000 students—a number that will seem quite small when compared to its current body of 30,000+ students. Student enrollment would almost double in the following ten years, exceeding 15,000 in 1967. The university’s student body overall had more than doubled during the 1950s as well, and the numbers would continue to rise thereafter.

This period of growth, however, would cause problems for the university during the 1960s, as McGill’s small campus was called on to accommodate more and more students every year. During the 1950s, McGill had only two student residences—Douglas Hall and the female-only Royal Victoria College. In the early 1960s, the construction of McConnell, Molson, and Gardner Halls helped to accommodate the growing student body.

Although there are certain difficulties posed by today’s large student body, like class sizes and the accessibility of professors, the growth has also allowed for the diversification of the student body and facilitated intellectual developments and research. While the large population of McGill may remain a mixed blessing to current students, it is a defining part of McGill history, and the atmosphere of the university today.

A matter of gender

As a member of the graduate school of nursing, Betty’s university experience included high levels of female representation. Nana’s experience as an undergraduate was similar.

“We were half and half,” Nana says of classroom demographics, thoughshe said this varied according to faculty. “The odd [female was in these other faculties]. Even architecture.”

Indeed, in the 1950s, the gender divide was quite noticeable in some fields. In the graduating class of 1952, for example, there were no female students studying engineering, and only 5.7 per cent of the commerce class was female.

Not every faculty, however, contained such a large gender divide. In the Faculty of Arts, the amount of female graduating students actually outnumbered their male counterparts, with 64.8 per cent women (compare to the 66.6 per cent studying in 2011). In fact, women have outnumbered men in the faculty of arts ever since 1917.

In addition to the lack of female representation in certain faculties, MacDonald Campus offered women a science degree in “household science,” where they could study subjects including clothing and textiles, family and consumer studies, and food and nutrition.

Although many changes to McGill in the last 60 years have been specific to the university, some changes are the result of wider trends in Canada and the rest of the world.

“[Students] can [now] sit and watch your lectures on your laptops—the library was the place we worked. There was no such thing as getting things online,” Nana says.

However, some aspects of university life remain similar for students today. Like many current McGill students, Betty says that her grades were not the most important aspect of her McGill experience.

“I don’t think grades are totally indicative of what you have learned, because a lot of us are not good at writing exams or term papers or doing research of that kind,” she says. “But because you had broadened your horizons [at McGill] you were better prepared to deal with clients and patients. The exposure to Montreal and McGill … I’ve never regretted it.”

From the campus’ layout to the student lifestyle and workload, the McGill experience has dramatically changed over the 60 years since the 1950s. While students may no longer hitchhike to school or pay two hundred dollars in tuition, a look back on this time period also reveals commonalities between the university experiences of different generations. As the university continues to develop and add to this history, McGill’s rich past continues to pervade the atmosphere on campus.