Swipe right, swipe left.

This isn’t Mr. Miyagi’s new mantra in the latest Karate Kid sequel, but if you’ve used the mobile app Tinder, it may resonate with you as a mantra of sorts. Perhaps you’ve opened up Tinder on your phone before, only to realize 10 minutes later that you’ve slipped into a hypnotic, meditative cycle of swiping that you hadn’t planned on doing at all—perhaps even wondering: “What was I doing here in the first place?”

For all intents and purposes, Tinder is a social discovery app. The homepage of its website affirms this with their confident slogan: “Tinder is how people meet. It’s like real life, but better.” But once you move past the vagueness of an umbrella-term like “social discovery,” there is a more concrete reality that exists—one that the creators of Tinder don’t seem to acknowledge.

“Tinder is a social discovery platform, not just a dating platform,” wrote Tinder Cofounder and Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) Justin Mateen in an email to the Tribune. “All we are doing is facilitating an introduction between two people—what comes out of that introduction is entirely up to you.”

Honest as Mateen’s statement may be, it fails to address the remarkable shockwave that Tinder has sent through the world of dating and hook-ups since its launch in September 2012. Aside from all the dates and one-night stands the app has facilitated, the company is aware that at least 300 marriage proposals have been spawned from a Tinder match; that athletes at the Sochi games were using Tinder in the Olympic village to find desirable companions to spend their downtime with; or even that Sean Rad—one of Tinder’s other co-founders—is dating someone he was matched with by using his own app. The service that Mateen described as “an introduction between two people” actually does a lot more than simply introducing them: It gives them a hope—a fairly realistic one—that they’re talking to someone who finds them attractive.

The Tinder basics

Tinder facilitates its interactions with a double opt-in system that is tailored to appearance-based validation. The only people you can talk to through the app are those who have approved your profile and vice-versa. It’s a process that—aside from minimal information about someone that is hidden when their profile first appears—makes a small set of photos the sole criteria for judgment.

A swipe to the right of someone’s profile on the touch screen counts as a vote of approval, and a swipe to the left says ‘No, thanks.’ Users don’t rate each other at the same time, meaning that the fear of ‘face-to-face’ rejection is eliminated—a big part of what makes Tinder fun and stress-free to many users. If both have swiped each other right, Tinder informs them that they’ve matched and can begin communicating through the app.

We’re faced with ‘yes or no’ questions all the time in our everyday lives, often trivial ones like “Are you watching the Habs game tonight?” or “Do you want fries with that?” On Tinder, that question becomes, “Based on some very limited information and a few photos, is this someone I’d like to talk to?”

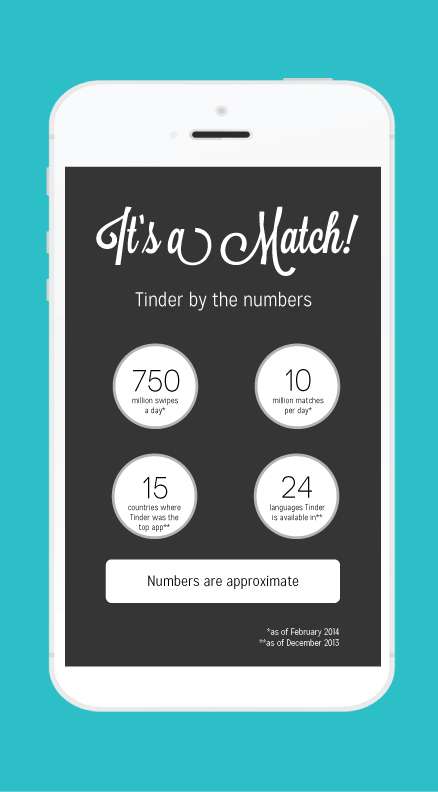

As of January 2013, Tinder had enabled over one million matches, which by December, had ballooned to 500 million. Now, the company claims to have recently crossed the billion-match threshold, continuing an exponential cycle of growth that shows no immediate signs of slowing down.

“Once Tinder’s user base started to take off, we had major scalability issues,” wrote Mateen. “In fact, we had to [restructure] the entire back-end so we could handle the growth.”

Bringing Tinder to campus

Tinder’s launch actually took place at the University of Southern California (USC), a decision that Mateen explained was in line with the marketing strategy of the app.

“We knew that if college students—who already live in a socially-charged environment—find value in the product, that everyone else would as well,” wrote Mateen. “We also knew that it would be easier to create value in a tight network where people have many friends and interests in common [….] Today we have a huge number of users in all age categories including the 13 to 17-year-old demographic.”

Although getting college students to buy into a form of technology-based dating has traditionally been very difficult, U2 Management student and Tinder user Thomas Brag pointed out that Tinder wasn’t marketing itself as a dating app.

“I think the fact that they didn’t really target themselves as a dating app might’ve been what caused [the app] to get [interest from] for the younger crowd,” Brag said. “I’m guessing that the way [Tinder] started it might’ve been what made dating online go from being un-cool to cool.”

In this ironic fashion, Tinder has broken new ground without specifically trying to do so. Without any guidance, college students—and other demographics—have implicitly harnessed the potential of Tinder as a means of improving romantic prospects in a simple, straightforward way.

“I see it as a hook-up app—that’s what I describe it as,” said Brag. “Personally, I don’t take it very seriously and I feel like [from] most people, when you ask them ‘Do you use Tinder?’ you get a laugh or something—it’s not really something serious.”

In fact, because of the high volume of profiles that a user can scan through and judge at once, the experience of using Tinder is often equated to playing a game.

“They’ve kind of ‘game-ified’ it,” explained Brag. “I think [because] you have a list of your matches, people kind of see it as your score or something [….] That makes it implicitly gameified—you want to have as many matches as possible.”

Can you judge an app by its cover?

While some may be lured by the prospect of matching with masses of people that have already validated their profile, others, like U1 Arts student and previous Tinder user Ariel Lieberman, are turned off by the app’s methods.

“The first thing you see about the person is their picture,” said Lieberman. “You don’t see their phrase or anything else about them [right away]; you judge them solely based on how they look, which, unless you’re looking for models or something, doesn’t really tell you anything.”

Mateen countered the criticisms of the Tinder swiping process’ superficiality.

“Tinder is honest and emulates human interaction,” he vouched. “For instance, when you walk into a coffee shop, the first thing you notice about [people] is their appearance—you’re either drawn to them or you’re not.”

Mateen went on to explain that even though the initial contact between two people prioritizes looks, it needs to be quickly fuelled by more than that in order to succeed.

“Once you engage in conversation, you look for commonalities such as mutual friends and common interests which help establish trust between two people,” Mateen wrote. “I suppose anyone who would consider Tinder superficial is really calling humans in general superficial.”

If we are to take Tinder for the social discovery app as the company says it is, then it shows that Tinder is factoring appearance quite heavily into the formation of relationships that may turn out to be purely platonic. When a user’s purpose on Tinder has nothing to do with finding a romantic partner, Tinder’s minimalist interface presumably offers much less value than other online methods of social discovery would provide.

Jui Ramaprasad, an associate professor of information systems in the Faculty of Management, not only graduated from the same USC campus Tinder was born at, but has also conducted extensive research in the field of online dating. She commented that Tinder’s looks-based validation doesn’t work quite the same way in a platonic context.

“If I say to somebody, ’Let’s go play tennis tomorrow’ and they say ’No,’ it’s not going to break my heart,” said Ramaprasad. “I don’t think you see as much inhibition in those kinds of things [platonically]. Sure, when you live in a new city you have to take advantage of meeting new people [through things like Tinder]. But there are many platforms out there that do that [which] have been very successful.”

Currently, the only feature on the app that gives the user any autonomy beyond the basic swiping and chatting is an option to make lists of various people that they’ve matched with, the idea being that matches can be compartmentalized into groups based on what they represent (i.e. joggers, people living in the Plateau, etc.). But on several occasions, the founders have alluded to future changes they plan to introduce to the basic Tinder interface that will make it more conducive to meeting people for specific reasons, giving users more of an incentive to turn to Tinder for something like the tennis match mentioned by Ramaprasad.

A new direction for Tinder?

For the past three years, Brag has been co-developing an unfinished social discovery website called Passion Snack, which aims to connect people in Montreal based on common interests. He feels that Tinder might have a lot to gain by proactively encouraging its users to use the app for interest-based purposes in a similar fashion.

“I think that could be a good way to grow,” said Brag. “Because I feel like a lot of people who use it just want to mess around with dating and maybe get tired of it after a few weeks. So maybe that could help it grow in the future and not become a fad, because I think that it’s in risk of having that happen.”

He was also quick to provide ideas for how to possibly implement that change.

“The thing right now that’s cool is that it’s very simple to use,” explained Brag. “So if they want to add things like being able to find sports partners or start a band, they should make sure that it stays simple and maybe categorize these different interfaces.”

Lieberman said that Tinder could only succeed in this respect if it added something more substantial than photos to the swiping process.

“If you wanted to use it for [interest-based] purposes, you should be able to register as a journalist, or an artist, or a musician,” said Lieberman. “If you’re a musician, you could put up songs, and people could swipe through your songs; if you’re a journalist, people could swipe through your articles.”

Even though Tinder has maintained its idealistic stance of being a platform for any type of introduction, Ramaprasad noted that it’s more difficult to stick to that mandate as a company tries to grow, bringing up the example of Friendster, a social networking and discovery website that launched in 2002 before going offline and eventually re-launching in 2011 with more of a social gaming angle.

“Friendster tried to mix online dating with social networks,” said Ramaprasad. “That was their goal, but nobody knew it; they just thought they were a social network. Maybe it’s a bit different today, but I think that trying to have multiple identities gets a little complicated.”

She also noted that Tinder needs to think seriously about how it will generate a profit before it makes any major changes.

“[The creators] need to figure out how to monetize themselves […] based on the dating because that’s where they have the biggest market,” Ramaprasad said.

Maybe it is in Tinder’s best interests to capitalize on what users have gravitated most toward early on and corner the dating or hook-up niche, or maybe it should continue to ride the wave and experiment. In any event, they have already conquered one of an app developer’s main challenges.

“One of the biggest issues for most [online] social platforms is the chicken and the egg problem,” explained Brag. “To get users, you need users [….] The biggest problem is how to start that viral loop that causes it to spread.”

Tinder solved that problem a long time ago with its simplicity and mass appeal, bulldozing through the difficult college demographic. The users are there, but the purpose isn’t. Up until now, people have been able to make what they want out of Tinder; to play with it, use it strategically, or perhaps just to feel validated by the number of matches they have. There’s no way of knowing whether Tinder’s flame will burn out like other fads before it, or if it will end up being to social discovery what Facebook is to social networking—a platform that has been accepted by pretty much everyone with internet access. It’s a long shot, but some people forget that Tinder is essentially selling the game that Mark Zuckerberg unveiled from his Harvard dorm room.

“That’s what [Facebook] was,” said Brag. “It was a way for you to rate how people look, and Tinder is pretty similar to that concept.”

It certainly is, except it also gives you the assurance of being validated in return before you even talk to someone; and evidently, that can go a long way.