After a year of living in Rez, I was overwhelmingly excited to finally find my own place. Not that I didn’t enjoy my experience in university housing—I was simply anxious to have my own furniture, decorate my own room, and cook in the kitchen I would share with my roommate.

When my roommate and I finally decided on a place, we barely glanced over the lease before signing it. Without doing any real research about Quebec leasing laws, we thought looking around the apartment and skimming through the agreement would be sufficient.

The landlord sent notice that our rent was going to increase as our first year of leasing was coming to an end, I couldn’t help but feel a bit irritated. Why was our rent going up? There weren’t any changes being made to the apartment or the building. Why did he choose to increase it now, and why by that particular amount?

Not entirely sure what to do, I followed the instructions on the notice, signing the paper to recognize that I accepted the increase. I wasn’t even too certain about what it meant to “accept”—what alternative did I have besides moving out? Out of frustration and without any real understanding of its reasoning, I complained that the increase was drawn out of thin air. I didn’t realize until much later that rent prices were a little more complicated than a haphazard decision by one person. Though increases are quite typical in the housing market, there are often other components of a lease that are decided upon by the landlord, not Quebec law. If my landlord was to add unique demands to the contract, I would not be aware that I did not have an obligation to adhere to it under provincial regulations—until I signed the lease, that is.

Luckily, there weren’t any other major stipulations attached to the contract, but my roommate and I were surprised to find that a few of the conditions on the lease were unique to our landlord, not standards established by the Régie du logement.

In fact, I didn’t even know what the Régie was. I was simply another student looking to sign a lease for the next three years until my time at McGill was over.

What is the Régie du logement?

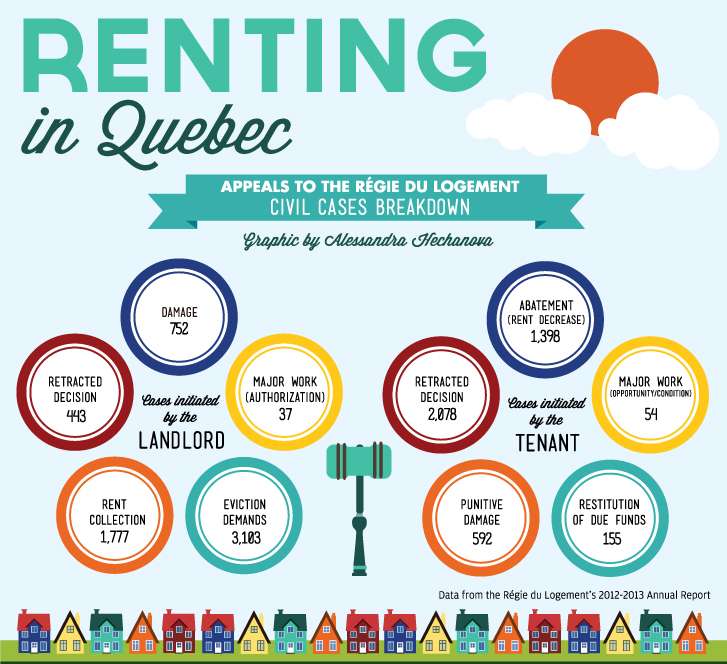

Quebec’s Régie du logement is an institution that holds jurisdiction over residential leases in the province. It works to create the standards and procedures for leasing, serve as a resource for potential tenants and landlords, and ensure the protection of leasing rights. In ambiguous or contentious situations between lessor and lessee, the Régie would provide jurisdiction, whether through pre-established laws and regulations, or via an application for a recourse submitted by either party.

Basic Laws and Regulations

The Régie outlines a series of regulations that dictate both the tenant and the landlord’s legal allowances. For example, the Régie’s website says it is legal for landlords to ask for references for credit checks and to require co-signers for students without an income, but it is not legal for them to ask for social insurance numbers or increase the rent mid-lease. Similarly, it explains that tenants must inform their landlord of a decision not to renew a lease, usually three months before the end of the lease —otherwise, the lease is automatically renewed.

Rebecca Dawe, the executive director of the Legal Information Clinic at McGill—a non-profit and student-run service that provides legal information to McGill students and community members—explained that in general, Quebec’s laws only delineate certain expectations from landlords.

“Some conditions can vary from lease to lease; for example, sometimes heating will be included in the rent, and sometimes it will be paid by the tenant,” Dawe said. “The law in Quebec does, however, have certain obligations that are mandatory for landlords. For example, a landlord cannot opt out of the obligation to deliver a rental dwelling in good habitable condition.”

Common Misconceptions

After realizing that my confusion over rent increases could be solved by looking into the Régie’s regulations, I set out to understand the guidelines I should have researched prior to signing a lease for the first time.

The Régie does not place a fixed rate for rent increase every year. Instead, it calculates rent variation by considering “the income of the building and the municipal and school taxes, the insurance bills, the energy costs, maintenance and service costs,” according to its website.

But then I realized that my options weren’t simply limited to accepting the increase or moving out. According to a document on lease renewal created by the Régie, the tenant can also “refuse the proposed modifications” and still renew the lease. In that situation, the landlord would then be able to file an application with the Régie. A commissioner will then follow the criteria for deciding on a rent increase for the apartment—which could be even more than what the landlord initially requested. However, the landlord and the tenant can still negotiate while an application is being processed at the Régie.

Just as I was under the impression that some of the conditions listed on my lease were standard procedure, many students have also fallen prey to misconceptions involving their apartment or lease. Unfortunately, when the turnover year-to-year is so high for apartment leases, students can get caught in a trap of common assumptions. According to Pamela Chiniah, the McGill Off-Campus Housing Coordinator, one of the biggest confusions students will have is with lease transfers.

“The big mistake that students do is they don’t contact the landlord when taking a lease transfer,” Chiniah said. “Let’s say I’m transferring my lease to you; I’m paying $700 rent. When you carry over my lease, for the four months you’ll be paying $700, but as of September, your rent [might] go up. Students don’t contact landlords to get this information [or…] get a previous copy of the tenant’s lease. Sometimes there are rules of the building that they don’t know. And very often when students do a lease transfer they don’t do the paperwork as they should.”

Another issue that students often aren’t aware of is known as a “finder’s fee,” an illegal practice often advertised as “buy my used furniture” for lease transfers.

“Finder’s fees started close to 10 years ago,” Chiniah said. “There was a housing shortage in Montreal [at that time].”

Chiniah explained that many people use furniture as an excuse to validate a finder’s fee.

“Let’s say I have an apartment [lease] that runs until August, but I’m graduating,” Chiniah said. “I want to give up my place, so I advertise; and when a student contacts me, I show them the place. But then I say, ‘If you want this place, you have to take it with the furniture [.…] So the person asks you for money, and [he or she does] not process the lease transfer until they get the money for the furniture.”

Because many McGill students are not from Quebec, it is common for people to assume that these finder’s fees are simply part of a standard procedure in apartment leasing. However, finder’s fees are illegal, and should be reported to the landlord if they become a problem.

But sometimes it’s not just the tenants who create extra charges against Quebec law.

“We see a lot of landlords asking students for key deposits, [which] is not allowed,” Dawe said. “According to the law in Quebec, they can only ask for the first month’s rent.”

Students from out of town will also frequently be misinformed about the relevant paperwork.

“Students […often] don’t know what the application form is in Quebec,” Chiniah added. “It’s a pre-lease. If you fill it out, bring it to the landlord, and he accepts it, you are legally presponsible for the apartment. Every year we have students with [multiple] application forms. Sometimes landlords are flexible, but they [might] say that deposit you gave [them…] will not [be given] back.”

Student Resources

For those who are looking to sign a lease—or for anyone who encounters issues with their apartment or landlord—there are many resources both on campus and around the city that can be useful. McGill Off-Campus Housing not only features an online apartment listing system, but also provides a collection of legal information on its website. It also provides “Apartment Hunting Info Sessions,” held annually for students seeking more information on leasing an apartment.

The Legal Information Clinic at McGill also offers free presentations on landlord-tenant law, which can be tailored to fit the needs of any student’s requests.

Apartment Hunting Info Sessions

Carrefour Sherbrooke “Ballroom”

Daily sessions, week of Jan. 20 at 2 p.m.

Daily sessions, week of Jan. 27 at 10 a.m.