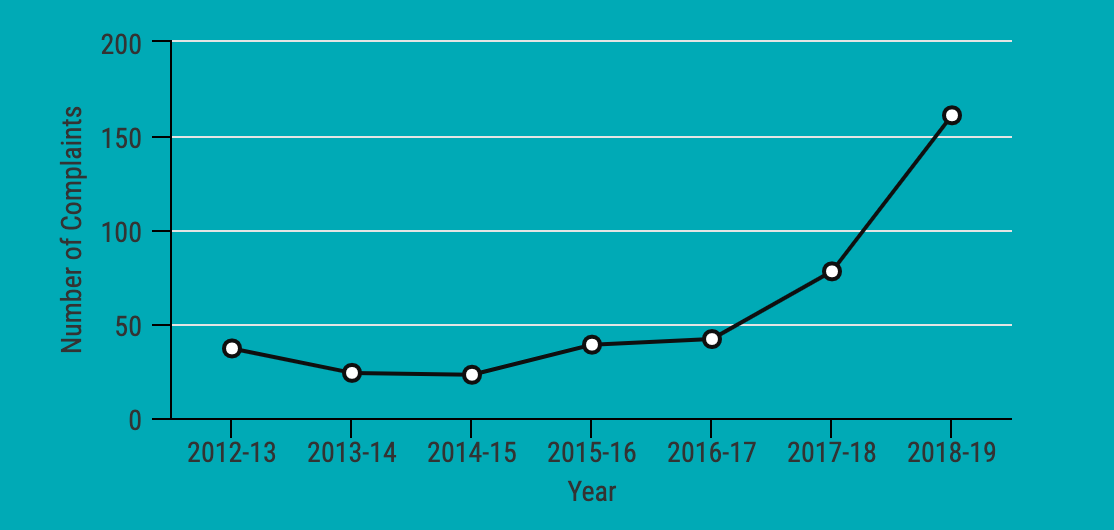

According to the Annual Report on Policy On Harassment and Discrimination Prohibited by Law, the number of inquiries and complaints increased from 78 cases last academic year to 161 in 2018-19. In the preceding five years, there has been an average of 33 inquiries and complaints. 12 per cent of the complaints were filed on the grounds of discrimination, 45 per cent on harassment, 12 per cent on sexual harassment, and the remaining 30 per cent were classified as mixed or other.

Initially adopted in 2006, the purpose of McGill’s Policy on Harassment and Discrimination Prohibited by Law is to establish an inclusive environment through prevention and response to harassment and discrimination.

The university has appointed Sinead Hunt, a Senior Equity & Inclusion Advisor (SEIA) to act as the primary contact for initial inquiries and complaints. Following contacting Hunt, the individual decides between attempting an informal or formal resolution through investigation, through Senate-appointed Harassment Assessors.

Professor Angela Campbell, Associate Provost (Equity and Academic Policies), emphasized the importance of the SEIA.

“The role of the [SEIA] is growing in scope and importance,” Campbell said. “This is a very positive development for the McGill community.”

Harassment and discrimination reports are investigated by Assesors: However, as of October 2018, reports of sexual violence are investigated by an external Special Investigator instead, in accordance with the Policy against Sexual Violence.

Whether the increase in harassment claims is due to an increase in complaints or higher awareness of the report is speculative.

“I have no evidence that more people are being subject to harassment at McGill, but [I] do see awareness of [the policy] increasing,” Campbell said.

Chloe Kemeni, Student’s Society of McGill University (SSMU) Anti-Violence Coordinator, tied the increase in complaints, in part, to campus discussions rather than policy awareness.

“The current dialogue that has arisen from [student-driven policies and groups] has given folks the tools to define their experiences and advocate for themselves,” Kemeni said. “For those doing equity work on campus or in student governance, this is part of [our] daily discussions, but I’m not too sure that McGill has done an adequate enough job in communicating the policy in a way that is accessible to all.”

The report also proposes a working group to ensure that the policy is implemented in an appropriate way for the university’s needs and goals; however, the group’s members are not specified. The group will undertake policy revision in the present reference year (Sept. 1 2019 – Aug. 31 2020).

“It would be baseless to have a committee that does not have representation from racialized students who are most impacted by discrimination and harassment,” Kemeni said. “I don’t know if there is a clear cut answer to the question [of what McGill can do to reduce incidents] since at its core is a settler-colonial institution with deep ties to slavery.”

The report also recognizes the demand to formalize the process for investigating complaints.

“Questions arise about whether our current model, which entrusts investigations to Assessors who have full-time positions disconnected to the Policy at the University, is sustainable, especially as the number and complexity of cases arising under the Policy grow,” the report reads.

As a result, a coordinating assessor has been assigned to this role on a full-time basis.

The report recognizes that measures of isolation cannot transform the culture that surrounds harassment.

“It would help to create a culture in which students feel comfortable reporting, but which also sends a signal to those enacting harm that their actions have recourse,” Kemeni said. “As of now, we tend to protect those who are most harmful, while isolating and retraumatizing those harmed.”