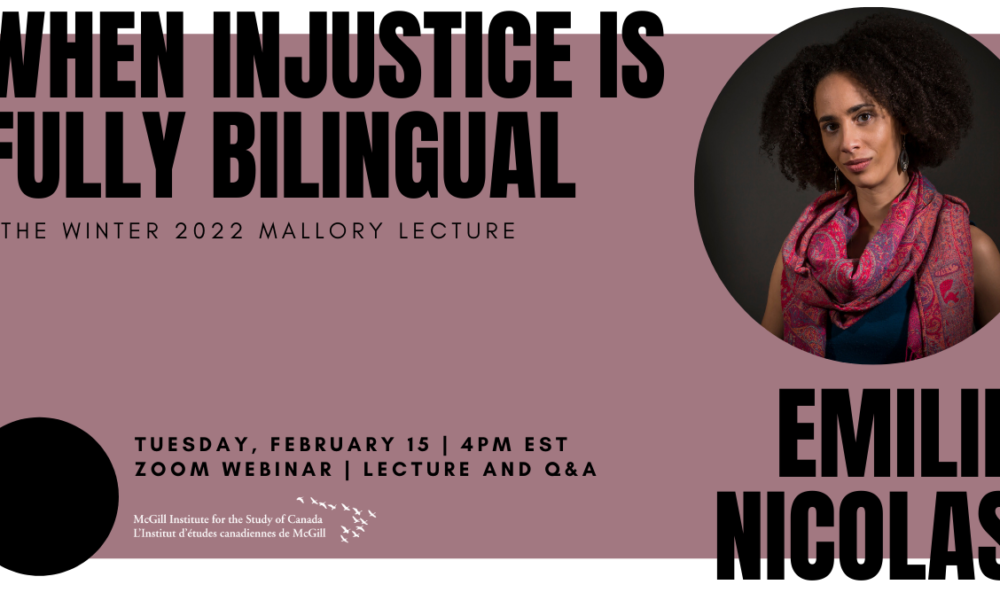

Emilie Nicolas, a columnist for Le Devoir and the Montreal Gazette, took to the virtual stage on Feb. 15 for this year’s Mallory Lecture, speaking about language barriers to anti-racism work. The McGill Institute for the Study of Canada (MISC) hosted the talk.

Nicolas introduced her lecture by describing a “war-time story.” The spring of 2016 saw numerous manifestations of systemic racism that mobilized many Montreal activists, including Nicolas herself. Investigations into the Val-d’Or police over allegations that a retired police officer sexually assaulted multiple Indigenous women, and the Montreal police killing of Jean-Pierre Bony contributed to a larger call for immediate and institutional change.

Nicolas noted that systemic racism in the province is often regarded as a foreign influence rather than a homegrown set of ideas, practices, and institutions.

“[An] accusation was that systemic racism was an English concept, it was an American concept that we were importing into Quebec society and that Quebec society was different,” Nicolas said. “Quebec society was always [framed as] welcoming and peaceful and tolerant […] and we were trying to put English ideas into Quebec society.”

Nicolas highlighted the tendency of settler-colonial states around the globe to deny their own systems of oppression. While countries like the United States, France, and countries in Latin America hold different narratives surrounding their histories of institutionalized oppression, a common thread remains: People who deny the existence of systemic racism within their states.

“Canada is one of the most successful marketing campaigns of all time,” Nicolas said. “The whole idea about niceness and politeness and all of that being put in a position with the violence of the United States is one of the core, founding mythologies […] around Canada.”

Nicolas feels that many English-speaking Canadians continue to hold such a narrative. On the other hand, French-speaking Canadians perceive themselves as the minority group in Canadian society which, according to Nicolas, allows them to deny their own racism. She gave the example of the little-acknowledged history of francophone Quebecois nuns being deeply involved in the residential school system.

“There was a widespread perception that residential schools were an English thing, were a British thing, and that French-Canadians didn’t do that and didn’t participate in that,” Nicolas explained. “More than half of the residential schools in this country were operated by oblates that are based in Montreal and were recruiting French-Canadian Nuns from the Saint Lawrence river [….] There was a lot of denial when that aspect of the story started to be covered.”

This denial and air of moral loftiness, according to Nicolas, can be exhausting for people trying to advocate for racial and social equality across the board.

“There is this hockey game going on […] and people like myself are the puck. We’re not even players,” Nicolas said. “[The] treatment of racialized folks and Indigenous folks and Black folks are argument points that are used to […] prove that you have the better social model or you have the moral high ground, which is a way to produce the very idea of white supremacy, which is about civilizational superiority. It’s a vicious circle.”

Blair Elliott, the communications and events associate for MISC, stressed the importance of learning from people like Nicolas.

“It’s important not to tokenize these issues, and to recognize that the work of advocating for decolonization, antiracism, and social justice is not only complex but also constant,” Elliot said. “It’s also important to remember that these conversations cannot be isolated from ongoing policy discussions.”