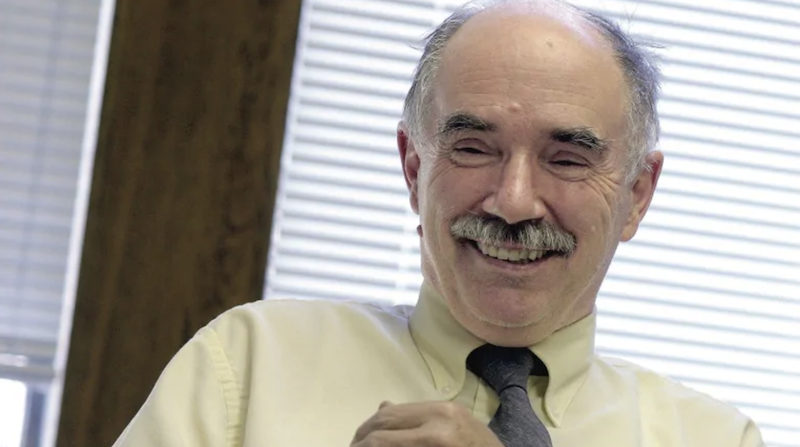

On Sept. 3, the McGill community lost 81-year-old Desmond Morton, an esteemed author and professor whose contributions as a ‘historian of conflict’ earned him numerous accolades. Morton was the Hiram Mills Professor in the Department of History and Classical Studies at McGill since 1998. Antonia Maioni, the Dean of the Faculty of Arts, remembers him as an educator who could engage any audience.

“In him, students not only saw a true scholar of the past, but a narrator who brought history alive for them,” Maioni said. “He could tell you where Wolfe and Montcalm were at every moment of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.”

Born in Calgary in 1937, Morton attended the Collège Militaire Royal de St-Jean, the Royal Military College of Canada, Keble College at Oxford University, and the London School of Economics. Prior to teaching, Morton served in the Canadian Army for ten years. In 2004, he received the Canadian Forces Decoration for his service. He was also active in the Ontario New Democratic Party from 1964 to 1966 as the party’s assistant secretary.

In 1994, Morton assumed the position of founding director of the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada (MISC), which is dedicated to scholarship concerning Canadian history and politics. He laid the foundation of the institute’s success by embracing an interdisciplinary approach to his field. Antoia Maioni, who served as the director of MISC after Morton, describes taking over his position.

“He wasn’t a big man, but he left big shoes to fill,” Maioni said.

Throughout his life, Morton wrote over 35 books on the social, military, and political history of Canada. Although he was a historian, he was careful to not isolate the study of history from other disciplines. Elsbeth Heaman, 2017-2018 director of MISC describes the influence Morton had on her.

“Des always had one foot in academia, one in the military, and the third in public life,” Elsbeth Heaman said.“He delivered that to McGill students. I was on the edge of it, but I still felt its wonders.”

After his retirement in 2004, he continued his involvement at McGill as a professor emeritus. Morton’s lectures rarely involved traditional presentations; instead, he would display battleground scenes and speak about their details.

“In some respects, he had a very old-fashioned way of teaching.” Heaman said. “But it was also [centered around his students] and it felt timeless,” Heaman said.

Morton’s work did not go unrecognized. In 1985, he was named a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, and he later became an Officer of the Order of Canada. For his efforts to promote history in the public sphere, Morton was also recognized with the Pierre Berton Award by the Governor General.

McGill Professor of Urban Media Studies Will Straw, said that, despite Morton’s prominence, he never gave up his enthusiastic willingness to talk to anyone.

“He was quite the famous guy, but if a student or visitor from another country came into the institute, he would sit and talk to them without the impression that he was trying to cut it short,” Straw said.

Morton was known by his colleagues as an inquisitive man who did not believe in easy, straightforward answers. Heaman describes what Morton’s answer to a question as simple as ‘What is the day of Canada’s independence?’.

“Des’ answer never was July 1,” Heaman said. “It was part of a larger picture that was remarkably skeptical about the greater narratives that are passed onto us about Canada.”

To Morton, studying history was not only a matter of the past; it was intertwined with the future.

“He always had an idea of where he wanted Canada to go, not only where it had been,” Heaman said. “That’s hard to come by in a historian.”

In the wake of Morton’s passing, McGill treasures his contributions to the discipline of history. He will be deeply missed by his colleagues and students.

“I go to a lot of dinners—we all do. I always wanted to be sitting next to Desmond Morton,” Maioni said.