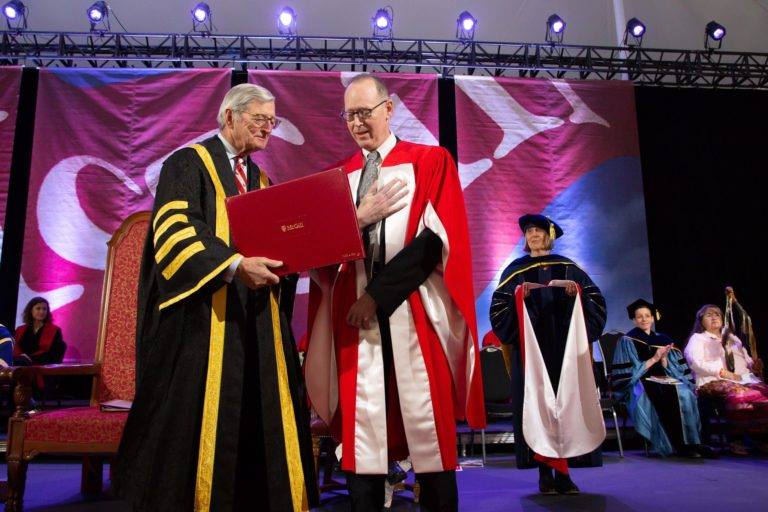

Doctor Paul Edward Farmer, or ‘Doktè Paul’ as his Haitian patients call him, is a medical anthropologist, physician, and professor at the Harvard School of Global Health and Medicine. He’s one of 14 people receiving an honorary degree this year, which are the highest honour McGill’s Senate can confer. Farmer is a co-founder of Partners in Health (PIH), an organization that provides treatment to populations with some of the worst access to healthcare services.

After graduating from Duke University, Farmer spent a gap year in Haiti and was appalled by the quality of healthcare for the poor and marginalized communities there. His experience in Haiti led him to co-found PIH in 1987. Starting with one small clinic in rural Haiti, PIH has expanded across ten countries, opening and running hospitals and clinics in countries like Lesotho, Peru, and Sierra Leone.

Farmer visited McGill to receive his honorary degree and sat down with The McGill Tribune for an interview. The transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

Q: How would you describe PIH?

A: PIH is a series of sister organizations. Each of them is focused on addressing the burden of disease, as well as gaps in the health system. In the language we cooked up as students, and we still haven’t gotten rid of it in the mission statement — we were trying to make a preferential option for the poor, or otherwise marginalized. We try to do more for them than anybody else.

Q: You travel a lot between Haiti, Rwanda, prisons in Siberia, and Harvard. Can you tell me a bit about that?

A: Not in 30-something years has it been about where I go. In Siberia, for example, what I saw was not the absence of a healthcare system, or the absence of healthcare professions. The collapse of a lot of social institutions following the end of the Soviet Union led to a lot of crime, which led to an epidemic of incarceration, which led to huge epidemics of tuberculosis. That’s radically different from rural Rwanda, where you had vaccine-preventable illness among children, high mortality, and epidemic disease. What unites all of those places, as well as Boston, is that there are health disparities in all of them.

Q: You majored in Biochemistry, but you switched into medical anthropology in your fourth year. Can you tell me a bit about medical anthropology and what fueled that switch?

A: I had no idea what medical anthropology was. I took medical anthropology because it had the word “medical” in it. In that class, you had to write a research paper, so I went to Duke Hospital, and they let me into the emergency room, and I was looking at health disparities, focusing on race, insurance status, and patterns of utilization. I learned that, particularly for African Americans, people were using the emergency room for primary care, for any kind of issue, because they didn’t have easy access to the healthcare system. It was a real revelation and got me launched into the field before I went to Haiti.

Q: You’ve received a lot of backlash for treating patients who have developed resistance to multiple drugs because medication is too expensive, with your critics arguing that the money could be better invested on prevention. What’s inherently wrong with this utilitarian approach in medicine?

A: I don’t know why that gets to be called utilitarian. To me, it’s a lot worse than that — it’s stupid. Especially tuberculosis, an airborne disease. In Siberia, what happens when you don’t treat drug resistant strains? They spread. I’m also very grateful for anthropology. When you’re told something is expensive, the first thing we should be asking is, “why?” By the time we heard the arguments about drug resistant tuberculosis and HIV drugs, we already knew to be suspicions of cost-related claims. It’s not like diamonds are put into TB medication.

Q: Mountains in Haiti are referred by the locals as “having teeth,” a testament to the steep and tough climbs; You have also made these climbs yourself in order to serve patients. Do you think that in order to provide good care you have to, in some way, suffer alongside the patient?

A: The idea that you should seek out your own privation in order to serve others — I don’t feel that way. But being attentive to other people’s problems and letting that wound you, I think that’s a very good thing to do. I don’t think it comes naturally to us, to imagine yourself in another person’s position.

Q: What are some lessons that you have learned in Haiti that Canada and the United States can learn from?

A: Training community health workers and rolling out a lot of services to prevent illnesses, and to address illness through a huge number of community health workers. Another is to focus on health equity.

Q: You’ve frequently mentioned that Lord of the Rings is your favourite book series. One quote from the series that a lot of McGill students might relate to is “Short cuts make long delays”. Could you speak to that and how it has applied to you?

A: I have read it so many times I had to switch to reading it in Spanish. A shortcut around, for example, drug resistant tuberculosis, or trauma care, or mental health, or cancer care, makes for long delays. And that means people perish in that delay. But sometimes shortcuts are good.

Other honorary degree recipients this spring include Nobel Laureate and physicist John Kosterlitz, jazz improviser Pat Metheny, as well as gene-editing pioneer Emmanuelle Charpentier.