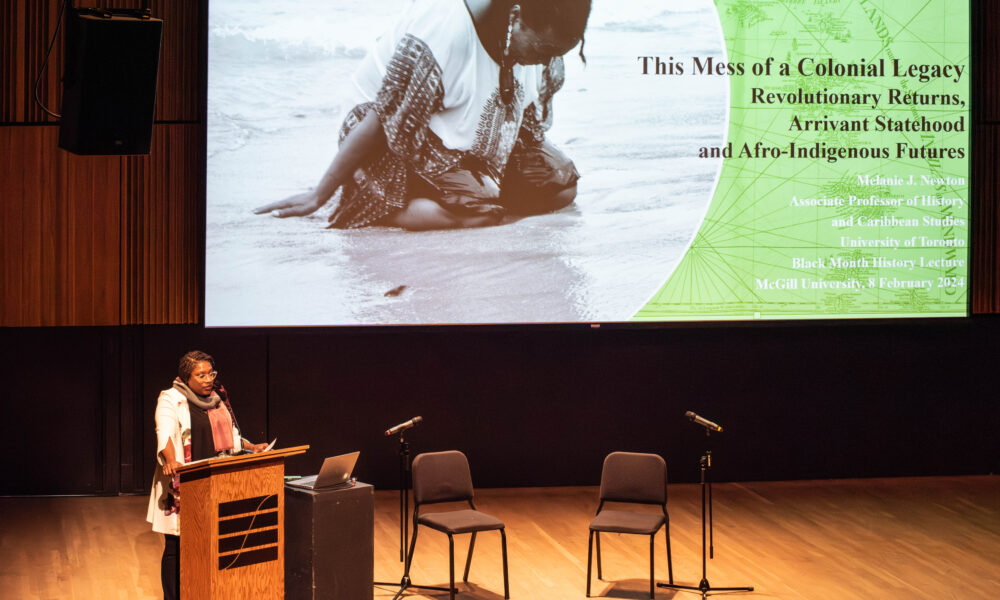

Students, alumni, staff, and Montrealers congregated in the Elizabeth Wirth Music Building on Feb. 8 to attend McGill’s eighth annual Black History Month Keynote Lecture, featuring Melanie J. Newton, Associate Professor in the Department of History and Graduate Associate Chair at University of Toronto. The McGill alumna, Rhodes Scholar, and former Coordinating Editor of The McGill Daily delivered her speech titled “This Mess of a Colonial Legacy: Revolutionary Returns, Arrivant Statehood, and Afro-Indigenous Futures,” inspiring the audience to build a more equitable future by reinvigorating the possibilities of Afro-Indigenous solidarity denied by colonial rule.

Newton’s presentation centred around the Garifuna—an Afro-Indigenous people from the Lesser Antilles—and their experience of European colonialism, in which imperial systems of power intertwined their histories with those of the Black enslaved people violently relocated to their land. Newton explained that Afro-Indigenous communities experienced “colonial shatter,” where the management of identity obfuscates claims to land, enables genocide, and places Indigeneity and Blackness as diametrically opposed to one another. Newton stressed that, to this day, Black nationalism within the Antilles continues to mobilize on the understanding that the people native to the land are extinct, just as they petition for direct recognition of their right to land in Belize with the Indigenous Maya people.

“In Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, Guyana, St. Vincent, and Belize, Indigenous and Afro-Indigenous communities have all fought, are engaged with legal battles against their national governments, who often do not have any constitutional or legislative recognition of Indigenous peoples within their jurisdictions,” Newton said.

However, Newton also affirmed that Caribbean states can act against this injustice through Caricom’s 10-point plan for reparatory justice—a plan that compels former colonial powers to apologize to African nations and provide them with sustainable development support and reparations. The plan seeks to create a future where Indigenous peoples like the Garifuna can return to their land through systems of reparative justice and coexist alongside their Black neighbours, a society that colonialism denied. Newton referred to this future structure as an “arrivant statehood,” through which Caribbean states must take decisive action for success.

During the question and answer portion of the event, Newton also spoke to how, as a student of German and British imperial history and eventually as a teacher, erasure so often operates through the classroom.

“I remember there was this one class I’ll never forget, this it was 2004, and there was this […] Mohawk student, she always sat in the front, she was so keeen she was so interested,” Newton said. “But I had also learned all of those narratives about you know sort of Indigenous people having all been killed and so on. When I first started teaching here in Canada, I’d see my students writing using the word ‘natives’ in their papers and I would circle it and say ‘who’s native to the Caribbean, who’s Indigenous in the Caribbean?’ Then I’m like ‘where the hell are they getting this stuff from?’ and I’m realizing, it’s coming from the stuff I’m teaching. I want to think about this differently.”

Inaara Ismail, a first-year master’s student in Science and Public Health, was intrigued by an opportunity to reflect on her knowledge of colonialism from an Indigenous perspective.

“Hearing that from a different perspective and seeing what can be done to address barriers that still exist [….] Part of it was also in support of solidarity, being from an ethnic minority myself, wanting to support other people of colour,” Ismail said.

For other attendees, like Donalee, a McGill alum practicing social work who preferred to be referred to by only their first name, Newton’s speech was an awaited moment of reprieve. Donalee emphasized that Black History Month at McGill serves as an opportunity for community building in a fashion that work and academic environments do not offer.

“I like being around other Black community members […] [to] see people that I know [….] It does bring something to me that I can’t always get outside of the nine-to-five, and other commitments, to even just be in this space where you can feel comfortable,” Donalee said.

Newton ended her speech on a note recognizing adversity, but also possibility, saying, “There is a different future coming. What it looks like, I cannot say.”