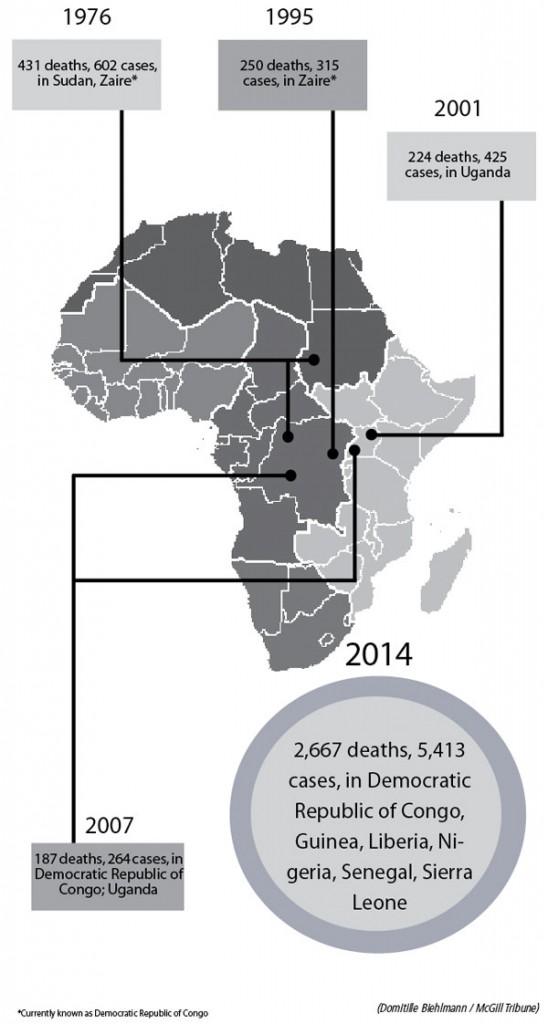

Kaci Hickox, a Maine nurse who has worked with non-profit medical humanitarian organization Médecins sans frontières (MSF) to treat Ebola patients in Sierra Leone, spoke to members of the McGill community on Thursday about the circumstances of the current Ebola outbreak and the challenges that need to be overcome in order to beat the disease.According to Hickox, doctors have been familiar with the Ebola virus for decades. The first human cases of the disease date back to 1967, and over 20 outbreaks have followed since, primarily in Central Africa. However, the 2014 outbreak was the first to occur in West Africa, with Sierra Leone having the highest number of cases, followed by Liberia and Guinea.

“The current outbreak has seen more cases than any of the previous outbreaks, with over 20,000 affected in all of West Africa,” Hickox said. “[There are] public health laboratories and hospitals in the U.S. that have been designed to accept Ebola patients or Ebola samples [.…] We’ve been in this outbreak for over nine months and we still have as many being constructed as there are any opened.”

Hickox also drew on her experience to address the fear and stigma associated with Ebola. Upon returning to Maine last October, Hickox was faced with a 21-day quarantine, despite having no fever and testing negative for Ebola. She spoke against the quarantine order, condemning it as “unethical” and “unnecessary.” A Maine judge later ruled in her favour, reducing the length of the quarantine to four days.

“There are so many voices of public health experts who have said these policies don’t make sense,” Hickox said. “All [the policies are] doing is increasing fear and stigma and discrimination, and when those things happen, Ebola wins.”

The Government of Canada put new public health measures into effect on Nov. 10, 2014 to prevent the spread of Ebola to Canada. The new policy, which can be found on its website, states that the necessity of self-isolation will be decided by quarantine officers on a case-by-case basis.

“All travellers coming into Canada with a travel history from the outbreak regions will need to be monitored for up to 21 days,” reads the policy. “Health care and humanitarian workers returning from outbreak countries who are not presenting symptoms will also be required to report to a local public health authority, monitor their temperature twice a day, report any planned travel, and immediately report any symptoms. Quarantine Officers will decide on a case-by-case basis if self-isolation is required.”

Hickox disagrees with Canada’s policy. What is needed, according to her, is a policy that is “simple, clear, and evidence-based.”

“Such a broad, sweeping statement means there doesn’t have to be consistency, and [that the decision] can be based on public fear and not science, which I think is a very dangerous place to have a policy,” Hickox warned.

Hickox also highlighted the negative impact that quarantine laws have had on international response to the disease.

“USAID [United States Agency for International Development, a U.S. Government agency that has been seeking medical professionals to volunteer in West Africa] saw a 17 per cent drop in volunteer applications the two weeks after governors […] announced [an] in-home quarantine policy,” Hickox said. “[The policy] has made healthcare workers feel afraid and confused and less likely to be willing to respond.”

Professor Madeleine Buck of the Ingram School of Nursing at McGill, who was one of the organizers of the event, praised the lecture.

“We’ve had some microbiologists [come to McGill to] talk about Ebola, but no one to speak from the clinical side as well as the political advocacy side, so this was very interesting,” Buck said. “We hope to make this an annual event.”

Second-year medical student Kelly Lau, who attended the lecture, agreed with Buck.

“It was a really fantastic talk,” Lau said. “[Hickox’s argument that] political action against Ebola should not be motivated by fear, but rather by medical evidence […] was a really great point.”

Hickox said she believes that it is important to continue speaking out to make people realize that irrational fear of the unknown only manipulates politics, and that it is always better to listen to science.

“I know that we can continue to beat this disease, but we also have to beat the fear, the stigma, and the delayed response,” she concluded.