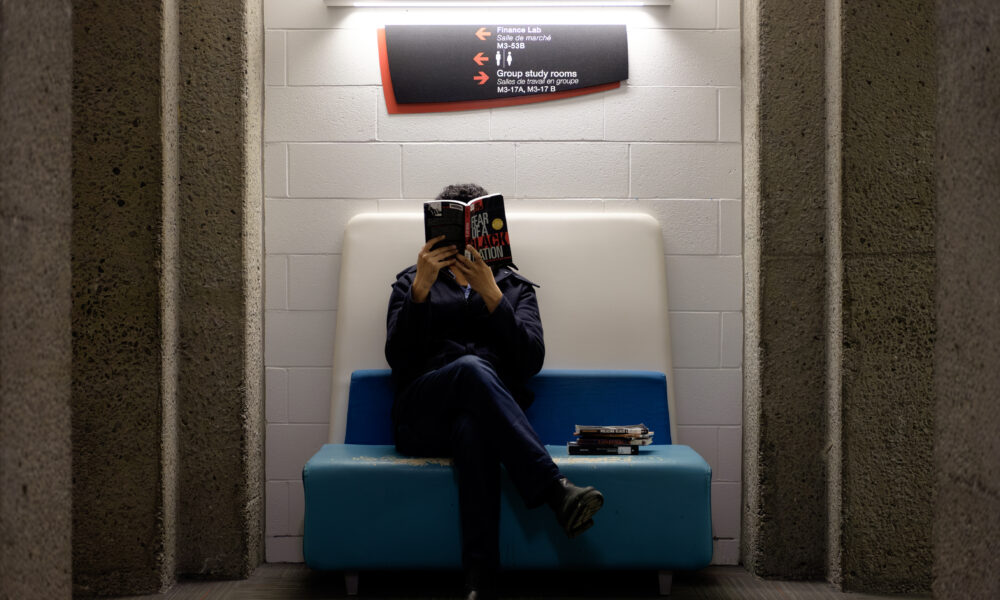

On Feb. 12, a small crowd gathered in the Rare Books Collection in McLennan Library for a talk by David Austin entitled “Black Politics in Dark Times: Revisiting Fear of a Black Nation After Ten Years.” Austin—a McGill alum and professor in the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada and in the Humanities, Philosophy, and Religion Department at John Abbott College—offered reflections on his 2013 book Fear of a Black Nation: Race, Sex, and Security in Sixties Montreal and on its second edition released in 2023. In the book, Austin discusses the history of Black political organization in the city and its connections to organizing beyond Montreal, as well as state surveillance and policing of Black political organizers.

“This book’s overarching thesis can be summed up in the following way: We live with the deep-seated racial codes that have roots in slavery and colonization, codes that were designed to discipline and punish people of African descent in the Americas—Black subjection to capital for the purpose of economic production,” Austin said, reading from the second edition’s preface. “Today, these codes are deeply rooted in a fear of Black self-organization and of Black folks in general, as well as Black-white and Black-Indigenous solidarities.”

During the talk, Austin reflected that much of the discussion surrounding the book tends to focus on two events—the 1968 Congress of Black Writers and the Sir George Williams protests in 1969—rather than on his larger argument. Austin highlighted that he instead views these events as “vehicles” to discuss the politics at play behind them.

One of the changes Austin made in creating the second edition of Fear of a Black Nation was including a map marked with the events discussed in the book. Not only does the map illustrate Montreal, it represents the city in connection to other locations of political importance, such as Detroit and New York. Rather than seeing Black organizing in Montreal during the sixties as a “micro-history,” Austin emphasized that it is entangled with national and transnational politics in an interview with The Tribune.

“Let’s think about Montreal as a kind of cosmopolitan composite, Caribbean […] Black Island that is tied to the politics of Indigenous struggles, Quebec nationalism, Canadian nationalism,” Austin said. “And then Black nationalism and Caribbean nationalism become part of that conversation […] informing those other conversations and […] interacting with them [….] So the particular site is Montreal. But it’s a universal expression of Black political struggles in multiple places, and a universal expression of what it means to be free and the struggle for freedom.”

Devanie Dezémé, U2 Arts, was among the talk’s attendees. In an interview with //The Tribune//, she explained that she attended the event to learn more about the history of Black people in Montreal.

“I grew up here in Montreal, but I never really had a sense of the history of Black people in Montreal, not just in the sixties, but even before that,” Dezémé said. “And you know, [Austin] was mentioning the archives [on Black political organizing] at McGill and elsewhere, and I think I’m going to try to seek them out.”

Camille Georges, another attendee, explained that through her position as Black Community Outreach Associate at McGill’s enrolment services, she noticed that the Black youth she works with were “missing” an education about Black history.

“This whole idea of identity, and how do you fit into this narrative is really interesting to me, because I’ve been following the work of David Austin for a little bit, and […] just to know our history is grounding to help us move forward,” Georges said. “I would consider myself a community organizer, so these types of talks are really important to me just to learn about what happened in the past.”

Austin also spoke to the importance of using Black organizers’ history to make sense of the present and stressed that “history is a methodology” for imagining the future.

“For me, there’s a different sense of urgency when it comes to invoking history. Because […] we’re talking about surveillance, we’re talking about policing. We’re talking about a myriad of issues and problems, incarceration. They were talking about all these questions back then, and we’re still dealing with them today. So how do those conversations from that time inform our understanding of those questions today? That’s the point.”