Despite the four years of negotiations on the lease, most students know relatively little about the new contract signed by the Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU) and the McGill administration for the SSMU Building.

More recently, the lease has prompted criticism from the student body, following the failure of the Building Fee in the Winter 2014 referendum period. The fee would have paid for the increasing rent and utilities costs that the lease entails.

As a result, cuts will be made to the 2014-2015 SSMU budget in order to fund the agreement. Some students have criticized the increased costs of the new lease that necessitate these cuts.

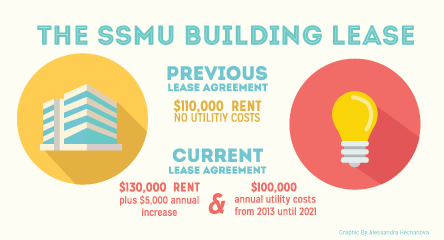

Under the previous lease agreement, SSMU paid $110,000 annualy for rent and did not pay any utility costs. With the new lease, SSMU will pay $130,000 this year for rent—a cost that will increase by $5,000 each year until 2021. SSMU is also newly responsible for $100,000 per year in utility costs.

Although the negotiations have been ongoing, the lease’s contents were largely confidential throughout this process. This week, the Tribune sat down with current and former SSMU executives to find out how the lease has evolved throughout negotiations and why it took four years to reach an agreement with the university.

The symbolic lease

SSMU’s previous lease expired in May 2011. In the interim three years, SSMU operated in the building without a legal agreement until the Board of Governors approved the current lease on Feb. 27.

Until 1999, SSMU paid a $1 symbolic lease for the building. The 2011-2012 SSMU executives initially argued for a return to this symbolic lease, but were unable to make progress with this stance. According to 2012-13 SSMU President Josh Redel, his executive team made the decision to abandon that line of negotiations.

“[The administrators] told us that [a symbolic lease} cannot exist in today’s financial realities,” he said. “There would be no way they would be able to support a building like that; they don’t have the money to support something on principles alone.”

Deputy Provost (Student Life and Learning) Ollivier Dyens said Quebec law only requires the university to provide SSMU with an office and furniture for free, which McGill offers through the 377-square metre executive offices. He said the university charges rent for the SSMU Building partly because it houses commercial operations that generate revenue.

“The rent is still very competitive when you compare it to the same amount of space in downtown Montreal,” he said. “We’re not trying to squeeze students at all; we’re just trying to have something that is good for both sides.”

Main topics of negotiation

Over four years, the negotiations were primarily concerned with topics such as energy costs, the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) system, and the duration of the lease.

According to Redel, energy was always the most contentious part of the negotiations. The administration initially proposed a sliding scale for utilities, where SSMU would have gradually taken on more of the costs until the society paid for 90 per cent.

Redel said one of SSMU’s biggest achievements in the negotiations was arguing against this sliding scale. Under the current agreement, SSMU pays a set 25 per cent of utility costs, while McGill pays the remaining 75 per cent.

“[In] the initial McGill [proposal] where they had that sliding percentage, the energy alone would have been millions over a few years,” he said.

An additional complication to the utilities negotiations was the state of the HVAC system, which, according to SSMU President Katie Larson, has not been upgraded since the building’s construction in the 1960s.

“The ducts hadn’t been cleaned in forever [and] the engineer came last summer and said [they were] not sure that this HVAC [was] going to last through the winter,” she said.

McGill at first asked SSMU to pay 50 per cent of the multi-million dollar HVAC project on top of the sliding energy scale, but executives argued successfully that SSMU should not be responsible for its maintenance.

“We should not be paying for [the HVAC system] because that’s the responsibility of the landowners,” said SSMU Vice-President University Affairs Joey Shea. “If the plumbing [stops working] in your apartment […] you’re not supposed to be paying to fix it [….] The owners of the building are responsible for large infrastructural issues.”

McGill has agreed to fund renovations to the HVAC system, which are scheduled to take place next summer.

One last point of contention during negotiations was the duration of the agreement. The administration advocated for a shorter-term lease, similar to the previous five-year agreement.

“You don’t know what’s going to happen five years down the road,” Dyens said. “Will the financial situation change? Will the market prices change?”

Having already spent several years in negotiations, however, the SSMU executive refused to accept a five-year lease.

“If it’s a shorter term lease, it comes up sooner and it gives [the administration] the opportunity to jack up prices for energy and rent even more,” Shea said.

“A really lengthy lease gives you the opportunity to finance projects over a long period of time— like renovating the cafeteria,” Redel said. “A longer-term lease is really important for making [these projects] a reality.”

One proposal from the administration involved a longer lease if SSMU allowed McGill Food and Dining Services (MFDS) to operate from the building, according to Shea. However, these plans were eventually scrapped.

“It was really important for SSMU to maintain its autonomy from McGill,” Shea said. “We knew at the end of the day we didn’t really want to go in that direction.”

Negotiations

The negotiations were also affected by other factors. Redel explained his discomfort with the negotiations, especially the way the administration initially asked SSMU to communicate through a proxy negotiator instead of directly through the deputy provost.

“The way McGill negotiated was awful—really truly awful,” he said. “They told us if we brought a lawyer, they’d leave. We started bringing a notetaker and they were up in arms. The administration constantly calls on SSMU to act responsibly and with due diligence, but when those same people are upset that we want to have thorough notes taken at a meeting [….] I think it speaks miles to the tone they set for the negotiations as a whole.”

Larson noted the difficulty of engaging with McGill representatives at the bargaining table.

“McGill shows up with what [they’re] going to make you pay and then you have to talk them down from it,” Larson said. “There’s a power differential that’s insurmountable.”

Due to such issues, this year’s executives refused negotiations with anyone other than Dyens, to whom Shea attributes their successful securement of the 10-year lease.

“It just shows how McGill has been negotiating this entire time and frustrations with miscommunications,” she said. “[Dyens was] new and [he wanted] to establish good relations with students off the bat [….] I don’t think we would have gotten [that] had we continued to negotiate with Morton Mendelson.”

Dyens said he could not comment on negotiations under his predecessor, Morton Mendelson.

“My negotiations with SSMU this year was done with respect and openness,” he said. “At no time did my administration pressure students to sign. We worked together to address the still unresolved issues and came very quickly to an agreement.”

Looking forward

After multiple years of work on the lease, SSMU executives expressed relief that the long negotiations are finally over.

“It’s not the symbolic lease, […] it’s not what we wanted, but it’s good for what I think McGill’s reality was,” Redel said.

However, because the proposed building fee created to pay for the lease did not pass this semester, SSMU faces financial difficulties in the upcoming year. The SSMU is currently planning to run the referendum question again in the Fall.

Shea emphasized the necessity for the incoming executives to stress the necessity of the fee.

“[Signing the lease] was a really long, arduous process,” she said. “What will be really important is to educate students on why we signed this lease.”

can anyone explain why letting MFDS in the building would of been a bad idea? I remember always wishing I could use my meal plan at the ssmu building as a freshman, and if it affords SSMU the money to have better services, all the better. Besides, that asian restaurant is by far the shittiest food on campus, I would way rather have bland caf food than those god awful balls of fat parading around as pork meat

I’m not exactly sure, but from my understanding it has to do with who has the commercial rights to the building. If we allowed McGill to operate within the Shatner Building through MFDS, they would decide which tenants would occupy the building. I think this (don’t quote me on this) may mean that the revenues from charging rent to the tenants would then also go to McGill instead of the SSMU. I’m not sure what that totals to, since it’s never specifically displayed in the SSMU Global Budget.

Also, I think one of the issues that they had with having McGill within the Shatner Building is that it would be an obstacle of achieving their vision of “student space.” For example, there would never be a Student Run Cafe (some would care, some wouldn’t) and the University may fight to close down some rooms to add in more tenants (i.e. closing down the Lev Buhkman and Madeleine Parent rooms, and making the entire floor a food cafeteria). This would result in less opportunities for students to use the building for student activities, but more so for the University to increase their revenues from the building.