The past month witnessed a renewed national dialogue on the topic of cyberbullying between youth, educators, and politicians across Canada. This new debate arose following the death of British Columbia teenager Amanda Todd, who took her own life after suffering through two years of cyberbullying and online blackmailing, as well as a physical attack by her peers.

According to Define the Line (DTL)—a research program based at McGill dedicated to the study of education, law, and policymaking surrounding cyberbullying—online bullying is “the use of a range of digital media and/or communication devices to post or distribute offensive and demeaning forms of expression.”

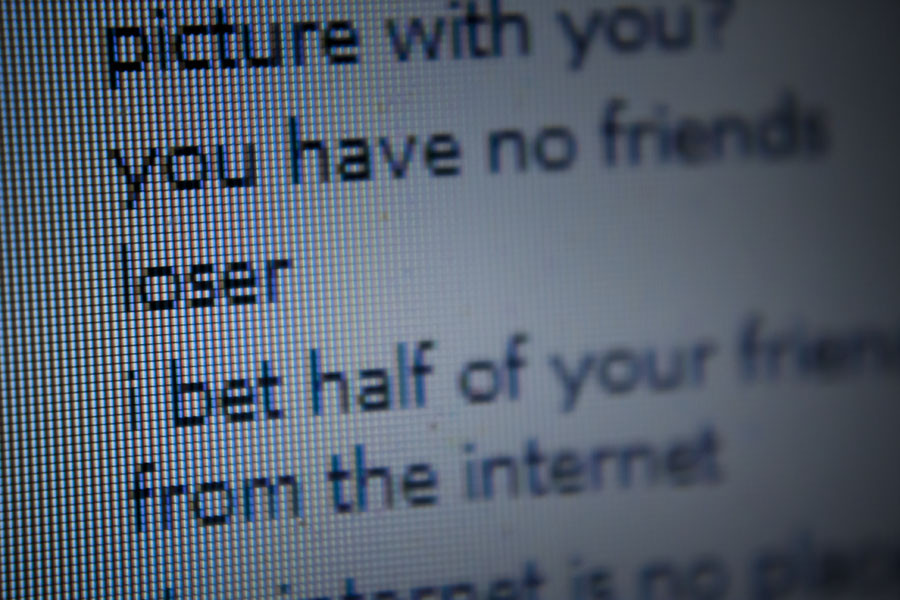

The DTL website notes that cyberbullying can be committed in many ways, and perpetrators and victims can be youths and adults alike. Cases can involve direct or indirect forms of exclusion and isolation, and of verbal abuse such as insults, rumours, and threats. Material posted and circulated online can include intimate pictures, videos, and information on the targeted individual.

According to the 2009 General Social Survey (GSS) on internet victimization, conducted by Statistics Canada, increases in the use of instant messaging and social networking sites have raised the instance of cyberbullying in a sample of Canadians aged 15 years and older.

Further results from the GSS survey indicated that seven per cent of Internet users over the age of 18 self-reported as victims of cyberbullying. The survey also found that girls are more likely to bullied online than are males.

Dr. Shaheen Shariff, associate professor in the faculty of education, international expert on cyberbullying, and director of DTL, explained why cyberbullying is a particularly difficult problem to prevent and address.

“Once bullying is online, anyone can participate, and it’s open to an infinite audience of adults and youth,” Shariff said. “Every time someone receives, reviews, saves, and passes on the abusive comments … the individual is revictimized.”

“The trouble is that the norms of online communication among kids have shifted to accept more joking and teasing, and youth don’t realize they are crossing the line to criminal harassment or defamation,” Shariff said.

Although the term ‘bullying’ is less frequently used in a post-secondary context, cases of online and physical harassment do arise on university campuses. To deter these, Articles 8b and 8c of McGill’s Code of Student Conduct and Disciplinary Procedures declare that no student may “knowingly create a condition … [that] threatens the health, safety, and well-being of other persons.”

Associate Dean of Students Linda Starkey told the Tribune that McGill’s position on physical and online harassment is one of “no tolerance.” Starkey explained that, if a student is found responsible for a violation of Article 8b or 8c in an investigation, the disciplinary officer assigned to the case will issue an appropriate sanction, which could include an admonishment, community service, and expulsion.

According to the 2010-2011 Annual Report of the Committee on Student Discipline (CSD), there were 68 allegations of violations to Article 8 of the Code adjudicated by disciplinary officers in that academic year. The report did not specify which violations pertained to Articles 8a, 8b, or 8c.

“It would be ideal if there were no cases, but sometimes things happen,” Starkey said. “And it may be a learning experience. It may not be malicious… it could be learning how others see one’s behaviour.”

Todd’s death also sparked debate in the House of Commons over what can be done to better address the issue of cyberbullying in Canada. On Oct. 15, New Democratic Party Member of Parliament (MP) Dany Morin called for the creation of a national anti-bullying strategy. However, some critics claim that action initiated at the local level, rather than by the federal government, might be more effective.

Shariff, whose work centres on policy and legal issues relating to online social communications, believes the most appropriate step to dealing with the issue of cyberbullying is education.

“Children are not criminals, and we need to educate them in legal literacy,” Shariff said. “We need consequences with educational messages using [technology] to engage kids to come to their own understanding [of the issue].”