Most students I know have at some point benefited from the services provided by Airbnb, whether for travel, a night out, or to make some extra cash on the side. However, in recent years, the rapid increase of Airbnb listings has become cause for concern for the housing market, as it hinders the ability of local residents to find affordable long-term rental locations. Left unresolved, this problem will cause the already severe housing crisis in major Canadian cities to get further out of hand. The main debate is whether it is the housing shortage or the proceedings of a free market that should be protected. Ensuring citizens can put roofs over their heads should be the priority, and provincial government regulation is crucial and needed immediately to this end.

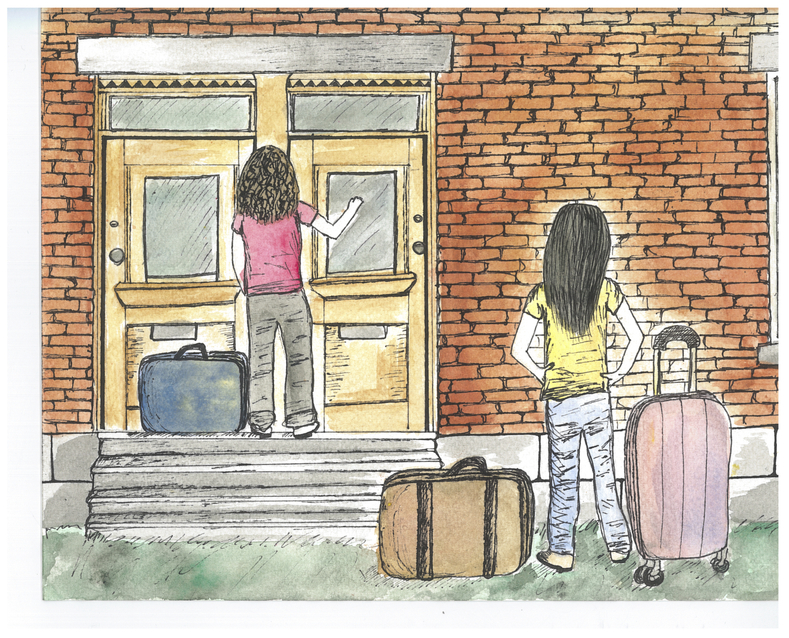

This summer, I found myself without a place to live in the town of Tofino, B.C., largely due to impact of Airbnb. Tofino is a small fishing town which has become a world attraction for surfers. As a result, the tourism industry has taken over the town and with it has come the convenience of Airbnb. I went to Tofino wanting to work and experience Western Canada; however, it was impossible for me to find a place to stay. Long-term renting was impossible in Tofino—locals blamed it on a housing shortage—yet there were over 250 listings available on Airbnb. The truth is that it was more lucrative for locals to post their empty rooms on Airbnb than it was to have seasonal workers rent the space for the whole summer—homes that would otherwise be available as long-term rentals were being listed on the home-sharing site, aggravating the lack of supply. As a result, the seasonal workers, many of whom came from Eastern Canada, resorted to living in tents or garden sheds.

Megan Dolski reported in The Globe and Mail that the town is unsure of how to handle this growing issue. According to Dolski, the town is focusing on adding new housing but has yet to discuss the ramifications of excessive Airbnb listings. This is a band-aid solution to a problem that demands to be properly confronted.

The situation in Tofino is not an isolated incident. As a recent McGill Urban Politics and Governance research group report shows, Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver are having similar problems, even without the significant influx of seasonal workers looking for housing each summer. These three cities alone totaled 81,000 active Airbnb listings this year and garnered $430 million in revenue last year, with every listing receiving roughly $5,000 per year.Of those active listings, there are around 13,700 properties across all three cities, serving as “de facto hotels” instead of as residential homes, meaning that no one uses that property as a residence. The number of Airbnb listings and the number of available rental spaces is almost equal, at close to two per cent. This heavily impacts the housing market, due to these “de facto” or entire-house listings taking away possible rental space from long-term residents. These “de facto” hotels are using Airbnb as a loophole to forgo the hassle of tourism regulations. The number of listings on Airbnb and number of new construction listings in some parts of Vancouver and Toronto are at a ratio of two to one. According to the report, the rapid growth of Airbnb listings has now outpaced new construction, thus impacting the net available housing stock.

The report makes it clear that the current regulations—or lack thereof—are putting the housing market in danger. So far, Quebec has been the only province to introduce legislation to control the number of listings by taxing revenue and making licenses mandatory for “regular users.” Unfortunately, Quebec forgot to define the difference between what a “regular user” and “occasional user” of Airbnb is. Fewer than one per cent of Montreal’s 6,356 full-time listings have acquired the license and are paying the 3.5 per cent revenue tax, making the law pretty useless.

In comparison, Berlin handled its Airbnb dilemma by completely banning most entire-home rentals. This approach is more concerned with the well-being of its citizens than the survival and flourishing of Airbnb. Canadian provinces must adjust their priorities to mirror those of Berlin’s policy, and protect their own residents from homelessness or from being driven out of city centers. Airbnb was created to provide an alternative to hotels, and therefore it would not be out of the scope of reason to heavily regulate the entire-home rentals now serving as “de facto” hotels.

Housing shortage must take precedent over the free market, as shelter is a necessity for life. A focus on the well-being of the state, and not just on the well-being of the economy, should be the Canadian government's priority. That said, it isn’t Airbnb’s responsibility to react to this dilemma, for their main function is to provide a platform. It is up to the municipal and provincial governments to regulate it, in ways such as licensing limits and restriction on entire-home listings.