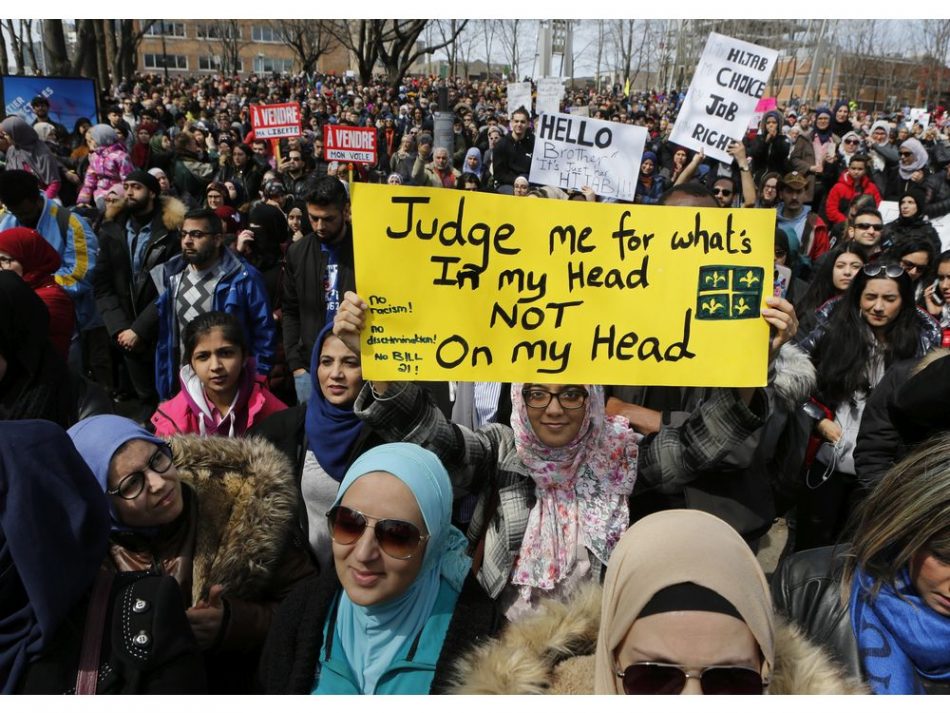

Bill 21, a law enacted by the Quebec government that prohibits public sector employees from wearing visible religious symbols, caused public outrage by disproportionately affecting religious minorities such as Muslims, Jews, and Sikhs. Introduced this past May, there was no shortage of speculation concerning how problematic the implementation of this bill would be. Since the law came into effect in September, Montrealers have been faced with the reality of the bill’s consequences: The implementation of Bill 21 has proven to be even more troublesome and divisive than its initial introduction.

Bill 21 did not include a specific plan detailing what enforcement would look like. Catherine Beauvais-St-Pierre, president of the alliance of teachers in Montreal, explained that school boards are learning how to apply Bill 21 day-by-day, as they were not given any instructions. One of the most ambiguous parts of the bill is the ‘grandfather clause’, which permits public servants who wore religious symbols before the law was passed to continue to do so as long as they remain in the same position. This means that there is no room for these people to move up in the workplace or change jobs should they wish to continue wearing religious attire. They are left having to choose between their careers and their right to religious expression.

Bill 21 was introduced to the people of Québec as promoting secularism and aiming to remove all physical elements of religious belief from the public sector. Unfortunately, the bill’s actual execution has had the opposite effect. As a result, public servants like teachers are put in an uncomfortable position, being asked intrusive questions about their faith. Religious attire has become dangerously political, leaving many Quebecers part of religious minorities constantly aware that they are ‘stuck in the middle of this debate,’ putting them at odds with those who support Bill 21 and creating tension in workplaces.

The discomfort felt in the workplace by those wearing religious attire carries over from the workplace to everyday life. Once exposed to strangers on the street, this discomfort becomes fear. This feeling is best expressed by Amrit Kaur, a Montreal resident and teacher who wears a dastar and feels that people are looking at her differently on the street now, the first time she has ever felt uncomfortable in Montreal due to her religion.

Hate crimes and xenophobic violence are increasingly being linked to Bill 21. Although Francois Legault, Quebec’s premier under the CAQ, has refused to acknowledge the link between the rise in violence with Bill 21, the two cannot be entirely separated. Bill 21 may not be the sole catalyst, but it has emboldened those who already held racist attitudes. The increasing rate of hate crimes in this province toward Muslims has coincided perfectly with the introduction of Bill 21. In any case, the CAQ’s statements when it comes to the effects of their legislation have been quite ignorant, which was demonstrated when a government agent stated very confidently that Bill 21 has created no tension or division.

“Although Francois Legault, Quebec’s premier under the CAQ, has refused to acknowledge the link between the rise in violence with Bill 21, the two cannot be entirely separated.”

The administration at McGill has released a meek 125-word statement about Bill 21 simply stating that they welcome diversity and are concerned that the law will affect some students’ lives. They did not mention that there are specific groups of students being disproportionately affected and have yet to acknowledge that the bill has been put into effect. McGill needs to support its students and ensure they are feeling safe on-and-off campus. This message may have been enough to make those in the administration feel better about themselves but it is not enough for students. To quote the Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU)’s statement, McGill needs to “publicly condemn the proposed bill and to provide meaningful support systems for the affected students […] to make campus as safe and equitable as possible.”

The law is even more intrusive than the author suggests. It prohibits certain categories of public sector employees from wearing any religious symbols, even invisible ones worn under clothing. So the law is not concerned with the impact a visible symbol might have on others, but with the employee’s own personal religious practice.