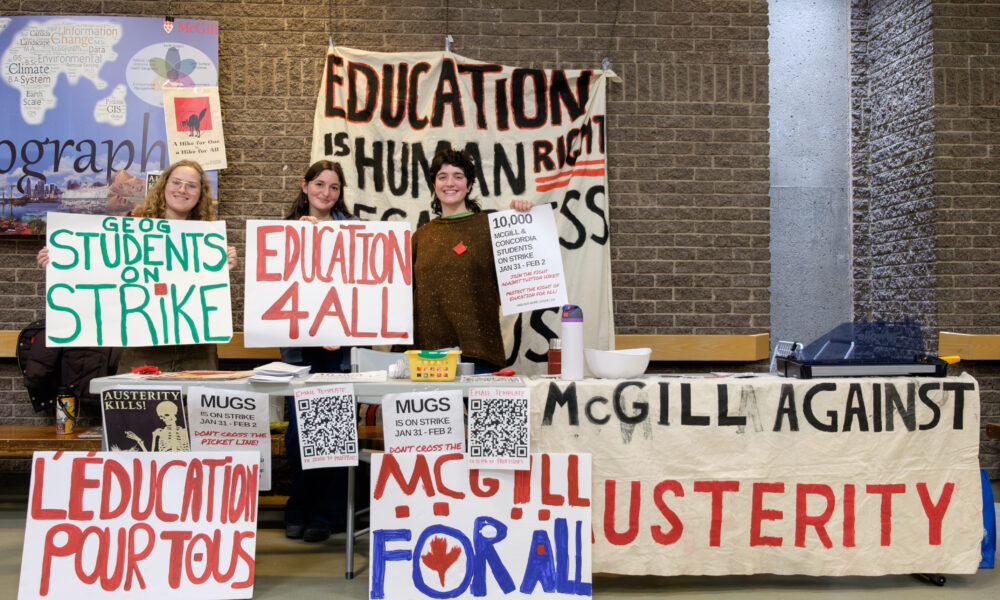

On Jan. 25, the McGill Religious Studies Student Association (RSUS), the Student Association of Sustainability, Science and Society (SASSS), and McGill Undergraduate Geography Society (MUGS) announced that their members would be on strike from Jan. 31 to Feb. 1. The strikes joined Concordia students in responding to the Coalition Avenir Quebec’s (CAQ) tuition increase for out-of-province and international students at Quebec anglophone universities. The hikes triggered dismay throughout the McGill community as a whole, and for good reason––the hikes threaten our right to an affordable education. As such, any effort to reverse them should be applauded. Despite RSUS and MUGS’s admirable sentiment, history warns that without proper organization their efforts could be in vain. To succeed, student strikes have to understand and react to their material conditions. Student strikes demand effective coordination—to truly propel change, students must break into the public sphere and seize collective consciousness.

Strikes have long been the tool used by unionized workers to make their voices heard; they voice their grievances with employers by refusing to work. For workers, striking is effective because it results in work stopping or slowing and their employer losing out on potential profit. Strikes work because they hit employers where it hurts—collective action leaves those in power with no choice but to listen. Last December, over half a million public-sector workers went on strike in Quebec in response to austerity measures from the CAQ. Workers in Quebec formed the Front Commun, an amalgamation of employees that collectively ratcheted up pressure on the government. The labour disruption’s climax was the seven-day strike in mid-December. As a result, workers were able to stave off the conservative CAQ cuts.

Quebec has a strong history of students striking to protect their rights. Since the Quiet Revolution of 1968, students have never been afraid to express their discontent with government bureaucracy. Tradition can be a rallying cry, but it does not do enough to spur change in today’s circumstances. While current movements carry the sentiments of the past, their tactics are misaligned.

In 2012, hundreds of thousands of Quebec university students went on strike in what is now known as the “Maple Spring.” The movement rallied against Liberal Premier Jean Charest’s tuition increases for in-province students, eventually forcing the province to rescind the tuition hike and taking Charest’s government down with it.

How did the Maple Spring achieve this success? By connecting with the public. The 2012 strikes expanded beyond university campuses, both literally and figuratively. Students blocked the Champlain Bridge, causing gridlock in Montreal, and picketed in front of government offices. Organizers formed alliances with some of the largest unions in Canada, who lent support in the streets and financially. By the end of the strike in fall 2012, people of all stripes supported the plight of the students. The 2012 student strikes were effective precisely because they were able to rally support and solidarity outside of campus.

Workers’ movements force the government’s hand by halting the economy; students alone unfortunately have not pulled the same weight. Linking the students and workers together in struggle, however, has the potential to secure gains for both parties. Greater numbers means greater pressure on the government. Public sector workers prove to be a powerful force time and time again—banding students and workers together would create a formidable force.

A student-worker alliance would further unions’ collective and broad reach. Take Stanley Grizzle, a leader of Toronto’s Division of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters elected in 1946. Railway porters in Canada were predominantly Black men who faced intense discrimination and exploitation. Grizzle used his unionized position to successfully advocate for fair treatment for all porters. Integrating students into the labour movement would only further its intersectional scope.

The McGill and Concordia student strikes mark a solid start of a larger movement. Grassroots initiatives can spark political change, but limiting themselves to a small segment of the population restricts their influence. Social movements must rally broad-based support to make a sizable impact. The right to an affordable education resonates universally; to protect student rights, organizers have to treat it as a cause that matters to all. If strikes remain confined to university campuses they will remain a university issue, giving the CAQ no impetus to hear student interests.