I was born in Montgomery County, Maryland, in 2004. The life expectancy of babies born at that place and time is 79 years. Three kilometres away, in Washington, D.C., it’s 74 years. I’ve spent most of my life in Seattle (in a county with a life expectancy of 83 years), where there’s comparatively ample access to education, health care, nutritious food, and economic opportunity. I’ve been lucky to benefit from these determinants of good health and a long life. But this is not the case for many Americans and Canadians. And it’s not the case for most of the world.

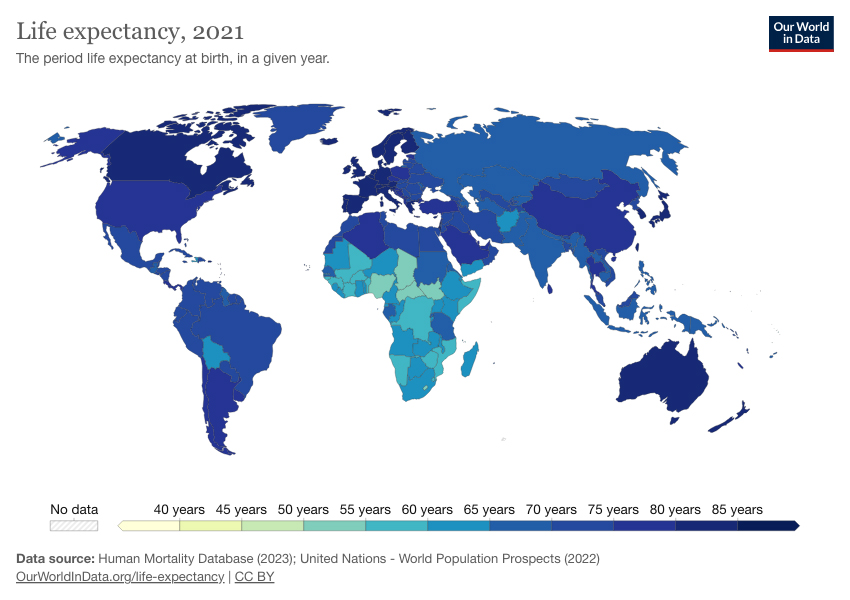

It is a grave injustice that the lottery of birth deprives some humans of time on Earth. Race and class have a significant role in determining life expectancy. Canadian men in the top income-earning quintile can expect to live eight years longer than men in the bottom. Majority-white Ontario has a life expectancy that’s 10 years longer than that of the majority-Inuit Nunavut. When we consider the entire globe, the disparity is even starker: Life expectancy in North America is 19 years longer than in Africa.

Life expectancy indicates a society’s ability and willingness to provide healthcare, education, security, and other important public services to its people. Most countries lack the resources necessary to provide these services, often due to unlucky geographic conditions or because of the lasting effects of colonialism. Wealthy, social democracies such as Sweden have both the ability and willingness to provide these resources (to Swedes, at least). However, the U.S.—and to a lesser extent Canada—have the ability to provide these determinants of health but comparatively lack the political will.

In the U.S., personal freedom and responsibility are integral to the rags-to-riches national myth and social problems like poverty are therefore framed as individual failures on the part of irresponsible people. This flies in the face of sociological research that shows the systemic nature of these issues. A growing chorus among philosophers and scientists also contradicts this individualist stance by positing that our actions (like all other phenomena in the universe) are physically determined, the outcome of neurological processes determined by our environment, genetics, and education.

I began to grapple with these topics while taking Jewish Philosophy and Thought at McGill. Philosophy relentlessly dissects our assumptions and forces us to justify our beliefs. Since becoming a philosophy nerd, I’ve become convinced that free will is an illusion, abandoning what little belief I had in the you-get-what-you-deserve American economic mentality. I’ve also adopted a moral outlook that primarily values the outcomes of our actions, like their effect on length and quality of others’ lives. I no longer feel that I can live a moral life by avoiding supposedly immoral things like lying and cheating, and I no longer base what I study, what I consume, and my aspirations on loose notions of what seems respectable or what my peers are doing. Through this perspective, I believe extending life expectancy is absolutely critical.

Social science research and basic human empathy command us to address life expectancy inequality. We must view issues such as education and healthcare in terms of years of life lost or gained. This means that supporting increased social spending—even at your own expense—is not merely a political preference; it’s a moral obligation. Simple choices, like voting for a politician who will invest in early childhood education instead of one who will cut taxes, affect the length of people’s lives. For Americans, it’s a national shame that health care is not guaranteed for all, while countries such as Costa Rica provide universal healthcare—at a lower per-capita price. We must consider international aid in the light of social benefit rather than through the lens of geopolitical strategy. A quick look at American aid highlights how the U.S. prioritizes maintaining global influence over humanitarian concerns.

Life expectancy inequality is a moral crisis, and we have the resources to solve it. By investing more in education and healthcare both at home and abroad, we can lengthen and improve people’s lives. I encourage readers to discover the life expectancy of their own geographic cohort, and to view the length of human lives as a paramount political and moral issue.