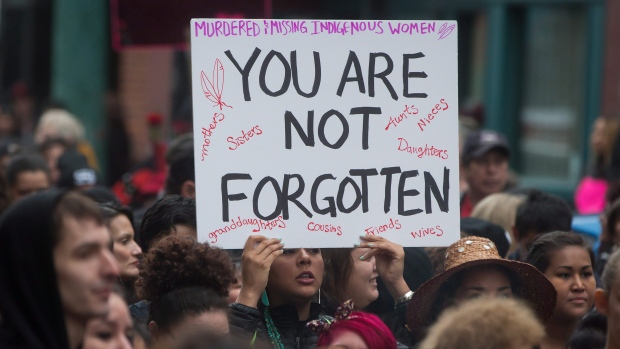

On June 3, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) released its final report. The volume, which is over 1000 pages long, concludes that Canada’s treatment of Indigenous people amounts to genocide and requires immediate action. Since the findings were released, much of the surrounding media coverage has disproportionally revolved around the use of the term ‘genocide’ instead of the report’s other findings and recommendations. Sadly, the MMIWG report has resulted in a political uproar among non-Indigenous politicians, with unaffected parties arguing over languages instead of processing the expert testimony and lived experiences featured in the report and developing plans for effective action. In the face of this ongoing injustice, it is easy to feel powerless and blinded by these debates. Rather than becoming lost in these debates, those concerned should work to develop their understanding of Indigenous issues, which go beyond the scope of the National Inquiry’s report.

There were over 2380 participants in the ‘Truth Gathering Process’ that formed the report. Of those, nearly 1500 of those were survivors or family members, 819 contributed ‘artistic expressions,’ and 83 were ‘experts, knowledge-keepers, and officials’ who provided testimony. Throughout the report, one can find devastating personal accounts, in-depth analyses, and 231 calls to action. It further solidifies the fact that Indigenous women are far more likely to be victims of homicide, sexual violence, and domestic violence than any other demographic. In fact, Indigenous women are 12 times more likely to go missing or be murdered than any other demographic of Canadian women, and their cases are too often mishandled by police and the courts. These facts require attention but have been largely overshadowed over what constitutes genocide.

Published with the final report was a 47-page supplementary document that contains an explanation for why the term ‘genocide’ is the most appropriate way to describe these injustices. However, the National Inquiry does not claim to have the authority to formally declare that Canada has committed genocide, and it acknowledges the complex and contested nature of the term and its implications. Socially, the word tends to only be associated with the widespread and systematic murder of a group of people: However, the word’s actual definition and original meaning is far more complicated, and according to the United Nations (UN) definition of genocide, it can include other actions such as physical or mental harm, the forced transfer of children, and ‘group conditions of life’ meant to cause physical destruction of the group ‘in whole or in part.’ Expanding the scope of the term does not discount the gravity of its meaning, especially when this renewed understanding still fits within the boundaries of the UN’s widely accepted definition. This nitpicking takes up too much of the conversation concerning the treatment of Canada’s Indigenous groups. These trivialities distract from the need to develop plans which sufficiently address the severity of the situation.

The report’s conclusion has attracted a range of opinions, many from people unaffected by its findings. Andrew Scheer, leader of the Conservative Party of Canada, argued that although the treatment of Indigenous people is a tragedy, it does not qualify as genocide, but rather as a unique issue which requires attention. The hypocrisy in this statement is evident—under former Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s leadership, a committee was set up to look into MMIWG cases but failed to call for a national inquiry into the issue, despite long-standing demands from Indigenous groups.

On the other hand, current Prime Minister Justin Trudeau accepted the genocide conclusion while highlighting the need for action, something he claimed his government is already focused on. However, this is also hypocritical: Trudeaumetre, a website started in 2015 to track Liberal campaign promises, documents how the government has failed to uphold many of its promises when it comes to Indigenous issues, such as providing them with a veto over their territories. Canadian politicians have consistently failed to produce results that match their supposed commitment to the wellbeing of Indigenous peoples.

Ultimately, whether or not politicians agree on the use of the term ‘genocide,’ no one can dispute that Indigenous women and their families continue to suffer greatly. The report’s release is an opportunity for non-Indigenous people to develop a deeper understanding which they can use to make more informed political decisions and be mindful of the suffering of the Indigenous peoples of Canada going forward. The upcoming federal election will surely prompt politicians to make promises to improve the lives of Canada’s Indigenous population, many of which will be empty. If able to vote, people must be mindful of who is promising what and how these promises align with their past actions, be them in the form of votes in Parliament or otherwise. If anything is going to change for Indigenous peoples on a systemic level, politicians need to be held accountable.

Those requiring immediate emotional support can contact the MMIWG support line 24/7 at

+1 (844) 413-6649. Long-term mental and cultural support is accessible through Indigenous Services Canada and other support networks. If interested, you can help by volunteering with or donating to one of Montreal’s many Indigenous programs and services.