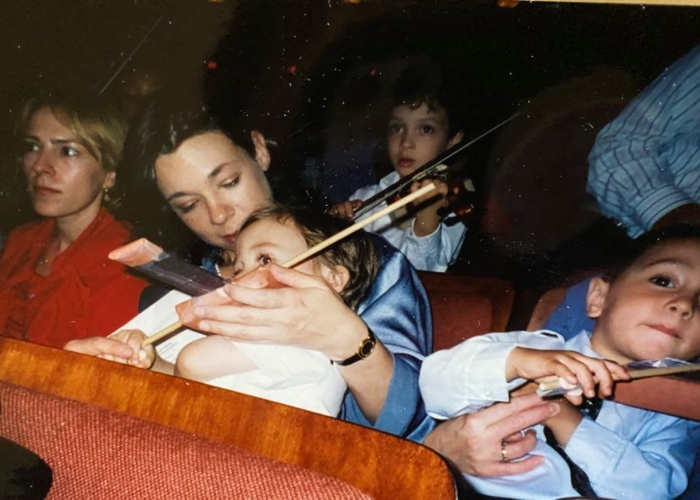

One of my earliest memories is of my mother handing me a cardboard violin and stick and having me bow along to Twinkle Twinkle Little Star. As the child of two classical musicians, I started learning music very early—at the age of two. Every day when I came home from school, I had to devote at least 45 minutes to practice before I was allowed to do anything else.

For much of my childhood, it felt unfair that I was forced to spend this much time on something that I did not always enjoy. While my classmates were playing video games or sports, I was stuck at home working on smooth string transitions that seemed to improve little, if at all, in the long term.

It was only when I turned 10—when I started taking lessons from someone other than my mother—that I took ownership of my practice time. I had to practice on my own, and if I did not improve significantly week to week, I faced disappointment and embarrassment.

From an outside perspective, practice appears simple: Just pick up the instrument and play. I had a rude awakening when I attended my first sleep-away music camp at 12 years old, where tight deadlines and entire days dedicated solely to music challenged me to improve quickly.

Under this pressure, I realized that practice was one of the most exhausting things I had ever done. One hour of intense focus made me weary. When I asked my friends and teachers how they practiced, my list of tips and tricks grew rapidly: Dedicating time to warm-ups and technique drills, dividing what I needed to work on into manageable sections, timing breaks every 20 minutes, and repeating drills were just a few of my strategies. I slowly started to plan my practice sessions through journaling. I eventually realized that practicing is a skill one must develop over many years. It is dedicated time for self-improvement, and if one does not invest effort, the only person cheated is yourself.

It can sometimes feel as though practicing is synonymous with suffering. While it certainly can appear that way at times, it can also serve as a form of meditation. The state of mind when one decides to dedicate the next hour to improving is unlike anything else: Time comes to a halt, and all worries melt away. Suddenly it is just you and the task at hand. In psychology, this state of mind is often described as “flow”—the mental state of immersed, energized engagement one reaches while performing an activity, being both fully concentrated and actively focussed on the process. Many attribute greater success and happiness to those who pursue these entrancing activities dubbed “flow activities” such as art, writing, or practicing an instrument.

Since coming to McGill, I have spent a lot less time practicing the violin. Over the pandemic, however, I have resorted to practicing music for solace. Whether it be shooting a basketball, learning a new scale on my viola, perfecting a track on Mario-Kart, throwing a frisbee, learning a yoga pose, or even chopping an onion, rigourous learning is incredibly fulfilling. Although I will not necessarily need or use all of these skills in everyday life, the grounding and satisfaction they provide is invaluable.

My father often says that people who succeed in music find success elsewhere, and while I did not fully understand this at first, I do now. A life-long work ethic dedicated to improving one’s craft and learning will not only help with success with the task at hand, but can also be applied to living a more well-rounded and fulfilling life.