This past summer, I decided to stay in Montreal instead of returning home to the States. In June, I walked around the McGill Ghetto and the Plateau, delivering my CV and asking for interviews. Working in the service industry means that you work with people, so, without fail, each time I handed over my meagre resume, the person behind the counter asked whether I spoke French. I replied with a scripted “un petit peu,” meaning “a little bit.” At McGill, it can be easy to shield oneself from the island’s Francophone roots. While this posed a minor inconvenience to my quest for summer beer money, for many, like the elder patrons of St. Mary’s Hospital, the French linguistic domination of Quebec can pose more serious problems.

In 2015, the Quebec government passed Bill 10: An act to modify the organization and governance of the health and social services network, in particular by abolishing the regional agencies. Along with a laundry list of other changes, the bill brought St. Mary’s Hospital in Montreal’s Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood under the administration of a new umbrella organization: The Integrated University Health and Social Services Centre (CIUSSS).

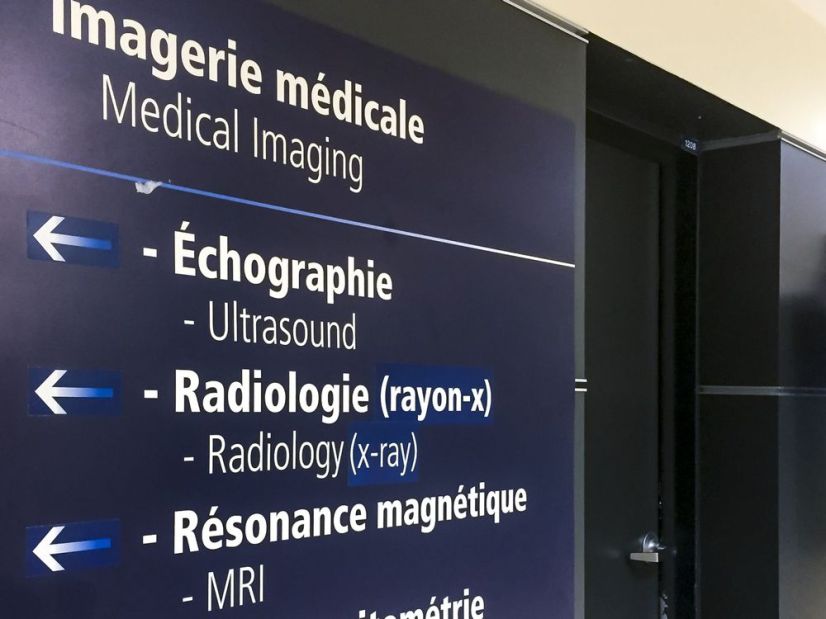

Shortly after the passage of the bill, the CIUSSS began replacing many of the informational and directional signs in and around St. Mary’s Hospital. While the signs formerly displayed text in both English and French in equal size and hue, the new signs display English text in a significantly smaller and lighter font than the French. The Users’ Committee, a St. Mary’s patients-rights group, immediately noticed the change.

The group expressed concerns about the practicality of the signs, specifically elderly patients’ ability to read the small text. Additionally, the Anglophone community in Côte-des-Neiges, which is larger than in many other areas of Montreal, has expressed broader concerns about a pattern of language legislation that is detrimental to English speakers. Although the provincial government has since tabled several amendments to Bill 10 in response to the public backlash, communal worries about what will happen to other Côte-des-Neiges hospitals once they are amalgamated under the CIUSSS umbrella remain.

Linguistically, the McGill student body shares similarities with the community of Côte-des-Neiges, and should therefore share its concerns. As a McGill student, the city is our campus. Montreal is a truly cosmopolitan environment, unlike any other. One of the things that makes this so is the combination of European and North American cultures and languages. It’s important, not only to the inhabitants of the city, but to me as a student, that the Quebec government strive to preserve French culture and traditions, linguistic and otherwise. That being said, the changes being made at St. Mary’s should not strike even the most traditionalist Quebecer as an effective strategy. The price we pay to preserve the French linguistic tradition should not be the Anglophone community’s ability to access healthcare services. This past year, McGill saw over 2,000 international students enroll from the United States. It’s important that these students feel secure in their ability to access health and social services if need be. Legislation like Bill 10 is not only detrimental to that security, but is attempting to address an imagined decline in the French linguistic tradition.

As provincial politicians and the media fuel the fire that drives these legislative changes, it’s clear that, while there are indeed fewer mother-tongue French speakers in Montreal than there were 10 years ago, French itself is actually on the rise. A study by Université de Montréal economics Professor François Vaillancourt found that French employers still significantly outnumber English ones in Quebec. The study also found that the percentage of French speakers in Montreal has actually increased, from 88.1 per cent in 1971 to 94.5 per cent in 2016.

While hysteria about the decline of French remains in provincial politics and the media, the language crisis is farcical. French is linguistically alive and well in Montreal. Changes like the ones resulting from Bill 10 at St. Mary’s hospital are not only impractical and unfortunate—they are combating an illusory problem. Access to healthcare is an issue that the provincial government professes to care about, but the debacle in Côte-des-Neiges proves the contrary. In Quebec’s misguided effort to preserve a linguistic tradition, they have made healthcare less accessible.