Relativism is one of the biggest threats to academic rigour in the humanities.

Institutions such as the Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU) and the McGill Daily, with their commitment to this dangerous brand of relativism—the concept that truth and morality are not absolute—validate the deep worries about educational trends professor Allan Bloom expressed in his seminal work, The Closing of the American Mind. Bloom’s arguments were originally presented within an American context, but today, they apply to McGill as much as any university in the U.S.

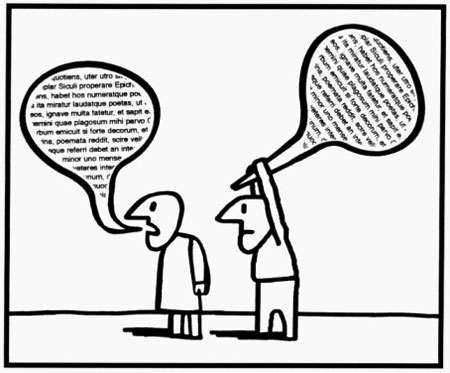

Bloom’s specific concern, the absence of the seminal texts of the Western canon in university reading lists, does not apply to McGill—the ‘Great Books’ are studied here. Yet, Bloom’s perceptive understanding of the process by which the ‘openness’ espoused by relativism leads to the ‘closing’ of meaningless discourse strikes at the core of what is wrong with the debate of ideas at McGill: Opinions are sacred, and knowledge is arrogance. Seeking to promote tolerance, students avoid challenging the views of others completely. Thus, the cultivation of fruitful dialogue, which comprises the real value of diversity, is lost. People’s ideas about the world are all considered equal, and derive their sole worth from having been chosen by their holder. If it’s my idea, it’s alright for me.

There is a widespread failure to distinguish between showing sympathy towards the ideas of others and blindly accepting them as equally valid as one’s own. The possibility of another person’s ideas being less valid, or, importantly, more valid, is absent in the consciousness of students today, and this absence of a belief in objective truth ruins campus politics and academic discourse. Its effect is particularly striking in the humanities, which are perceived as less capable of achieving objectivity.

This issue runs throughout contemporary society. Carlos Fraenkel, an associate professor of philosophy and Jewish studies at McGill, spoke to the importance of intellectual engagement in his Sept. 2, 2012 New York Times op-ed, “In Praise of the Clash of Cultures.” Fraenkel noted that “the privatization of moral, religious, and philosophical views in liberal democracies and the cultural relativism that often underlies Western multicultural agendas” pose serious threats to the culture of debate we ought to promote. Although the problem of extreme relativism is widespread, it is particularly pronounced here at McGill.

“Objectivity is dead,” or so the front cover of the Feb. 24 edition of the McGill Daily would have you believe. Any student who would deny the dominance of thoughtless relativism on campus need only refer to that edition’s feature article, “Unmasking Objectivity,” a disgusting progression of unjustified claims and an unsurprisingly selective collection of quotations. The self-referential article was prompted by a complaint about the Daily’s journalistic standards. In the Daily’s defence, the author presents a rambling and paradoxical assertion that objectivity is somehow bias towards those in power, because, as the piece assumes without substantiation, everything is ultimately subjective. Indeed, even the professions of those quoted were taken to be subjective aspects of reality; a Mr. Stefan Christoff is introduced as someone who “identifies as both a community activist and journalist” (emphasis mine). In some sense, their insistence on relativisim is fair; Objectivity is dead, but only at the Daily.

Moreover, the prevalent hostility to epistemic certainty creates a moral vacuum into which specific and often unsavoury moral agendas can enter. Hence SSMU has claimed for itself the institutional authority to force VP Internal Brian Farnan to make a public apology for emailing a harmless and funny GIF image to his fellow students., and hence, feminism and gender issues are given an exclusive spotlight in the moral program pushed by McGill Residences, Rez Project. It is not enough to attribute these cases to the general political apathy of university students, as is often done. Those who are involved in student politics have always been in the minority—the question is what accounts for the character of those in power now.

Only once we start taking each other seriously can we make any progress. Rather than being contrary to the liberal spirit, a recognition that not all ideas or values are created equal is conducive to productive debate. The basic acknowledgement that some ideas are true and some are false is a requirement for genuine intellectual activity. This is especially important for the functioning of the humanities, which lose their essential value when they degenerate into an undifferentiated chaos of opinion. To aspire to anything less is to succumb to intellectual laziness.