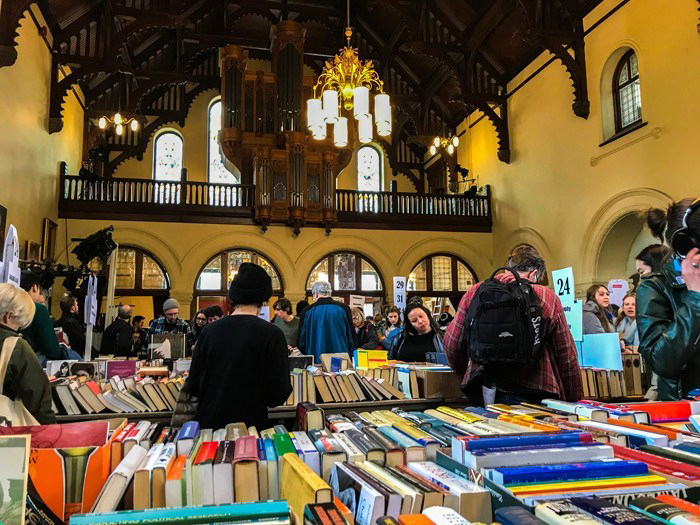

Despite being heard by few students during the fall of 2022, a death knell sounded marking the end of the McGill Book Fair. Started in 1972 by the Women’s Associates of McGill and the McGill Women’s Alumnae Association, the Book Fair is yet another victim of the McLennan-Redpath complex renovation. Organizers suggested on a Facebook post that the complex’s closure and a seemingly chronic inability to find volunteers made the event impossible to run. The transformation of the Book Fair from a vibrant community event to university lore demonstrates McGill’s inability to shield its cultural institutions from its relentless attrition.

Over the past 50 years, the Book Fair has contributed 1,948,000 CAD towards McGill Scholarships and Student Aid, generating three bursaries for undergraduate students. Though there is no doubt those bursaries will have supported many McGillians, to talk about the Book Fair solely as a financial conduit is reductionist. The Fair’s ability to affordably disseminate knowledge, foster community, and give participants a space to be intellectually curious meets and surpasses McGill’s own stated mission, a mission whose nebulous framework commits the university to scholarly excellence but not to community or curiosity. Yet, the Book Fair remains an un-resuscitated champion of McGill’s values.

The McGill administration is only interested in domains deemed important by Quacquarelli Symonds (QS)–– the company who releases the annual QS World University Rankings. Not every McGill student is willing to volunteer in extracurriculars that are not sexy or employable. If QS made an annual Book Fair a requisite to be a top 50 university, McGill would pour resources into the Book Fair, asserting that the event was “instrumental in delivering on its mission.” If McGill’s Medical or Law school requisitioned volunteering in a Book Fair for admission, to become a volunteer one would have to undertake a competitive entry. The problem is McGill’s neglect for the Book Fair is replicable; this apathy could claim other events. The Book Fair proves that even the most anticipated and successful events can simply cease to exist if they are not cared for.

Admittedly, I might be romanticizing the McGill Book Fair, but universities are romanticized institutions. With the world’s data readily and instantly available, what can a student gain or learn at McGill that they cannot online? Students may garner a community, exchange ideas, and ultimately, have the university legitimate their knowledge. At least two of those ideas are inherently romantic. If McGill cannot find the impetus to preserve the Book Fair, it not only fails to further the values of its mission, but it also fails to preserve the ideals that uphold the institution for students.

I mourn that I will never again arrive to class, albeit 10 minutes late, with a box of books in hand, full enough to gravely harm someone if I were to trip or buckle. Nor will I ever again strut campus gleaming with the knowledge that my purchase cost less than a sandwich and banana would at any McGill cafeteria. Worse even is that soon enough, I will be unable to quench the memory of the Book Fair by walking into McLennan Library and endlessly perusing amongst rows of books as a “study break.”

Though the Book Fair has gone, its end should serve as a reminder to nurture the cultural institutions we participate in. Take the example of Anne Williams and Susan Woodruff, two McGill graduates who attended the university in the 1960s and who were the latest co-directors of the Book Fair. They still post regularly on the Fair’s Facebook group, directing students toward book sales around Montreal or encouraging them to donate to the Fair’s bursaries. In this spirit, beyond demanding that the administration care for the culture that defines this university, students must remember that they are McGill’s vital cultural capital. If others cannot deliver on McGill’s stated mission, the onus falls on us.