There are many things in my life that I’ve accepted as inevitable: Breaking a bone, teenage heartbreak, and failing a final exam, for example, I have a strange sense that those events are predetermined. This may be symptomatic of a childhood spent in front of a television—each event in my life seems to fit an episodic narrative. When my parents announced that they were getting divorced, my first thought as a six-year-old was that I was going to be like Buster in Arthur. Growing up, I’ve always had a preoccupation with how the narrative arc of my own life will end. I have an unsettling feeling, clearer each day, that it might end like those of my other family members: With a chronic, hereditary neurological disease called Alzheimer’s.

Alzheimer’s has always been a part of my life: A sinister, underlying antagonist. The first funeral I attended was my great grandmother’s at the age of seven; she passed away from dementia. I have no memories of interacting with her where I don’t have to be reintroduced as ‘Wendy’s daughter.’ While she always greeted me with her trademark elderly-Chinese-woman enthusiasm, we never established an especially meaningful relationship.

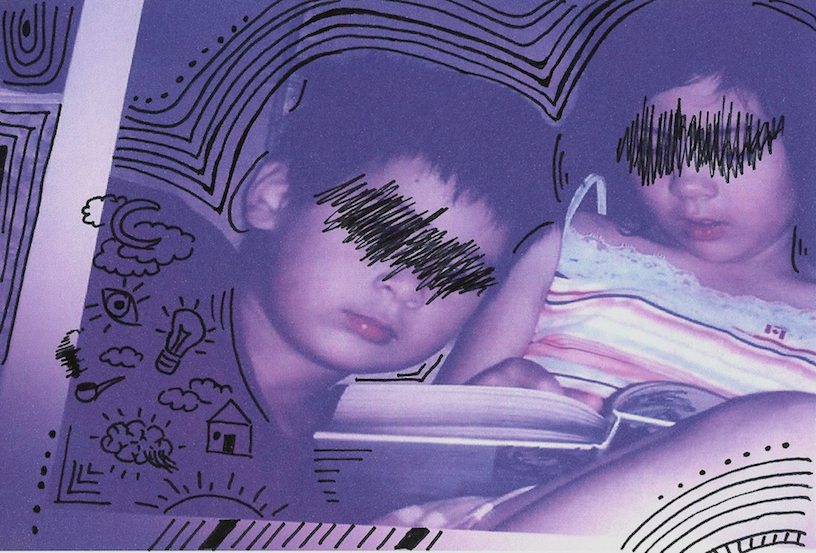

Alzheimer’s followed me into my adolescence with the death of my paternal grandfather when I was 10 and then my paternal grandmother this past spring. While my great-grandmother had lived blocks away from me as a child, I had not seen my paternal grandparents since the age of eight. They remain murky, greying figures in my imagination: I can recall my grandfather’s pipe and their foyer filled with my grandmother’s paintings. One of the reasons I had not seen them in so long is that my father simply did not want to go through the motions that accompany visiting a loved one with Alzheimer’s: The reintroductions, lapses of memory, and inability to complete simple tasks. There’s a haunting aspect to caring for a relative for a hereditary disease that, you too, might someday contract. I rarely thought of my paternal grandparents, who were peripheral characters in my life—besides, we lived in different provinces. The loss was softened by distance. What I do know is that, upon seeing a photograph of me, shortly before she passed, my grandmother made a stomach-dropping remark:

“Wendy looks so lovely here.”

Besides being mistaken for my own mother, this comment has always perturbed me: I wondered what else I might inherit from my mother if not her eyes and cheekbones.

I still have relatives on both sides with the diagnosis. The disease is still in its early stages, so I have allowed myself to keep a comfortable distance from the reality of the diagnosis and the outcome itself. Alzheimer’s seems like an invention of a Shonda Rhimes medical procedural drama until you are looking at its face in a hospital bed. Through all of this, I have become acutely aware of any symptoms my parents might display, such as minor lapses of memory. While this might be entirely paranoid, there’s always something that irks me every time my father forgets where he put his phone, or when my mother trips up on the names of one of my cousins. It could be nothing, but there’s an underlying fear that these small mishaps are indicative of something more sinister. Darkly, my mother will often joke that it’s “the early onset Alzheimer’s kicking in.” Premature though these comments may be, denying the fact that my parents, and by extension myself, have a high likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s would be to deny medical fact. To fool myself into thinking that I am an anomaly, exempt from a hereditary disease, would be laughably self-aggrandizing. Ultimately, there isn’t much I can do to prevent or predict my future besides a humble acceptance of whatever final moment lies ahead.