One would expect voter suppression and the arbitrary application of electoral rules to be the exclusive hallmark of states like North Korea, Syria, or perhaps Russian-controlled Crimea. The reality is we might have more in common with those regimes than we would like to believe.

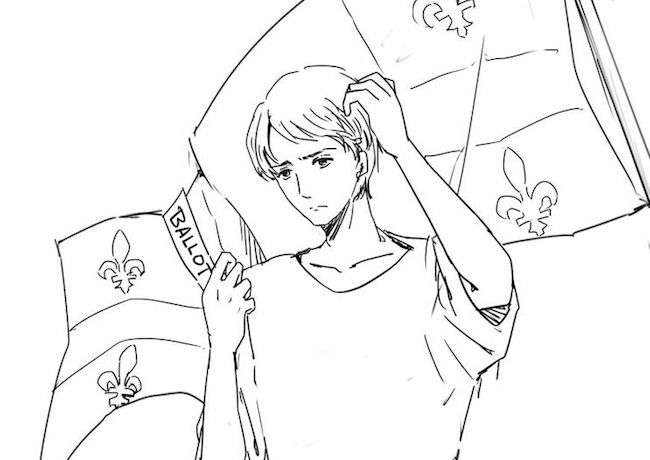

Official voting policy for Quebec reads as follows: one must be 18 years of age, and a Canadian citizen. One must also have been “domiciled” in the province for at least six months and have proof to back up this claim. It is this policy—and the arbitrary interpretation by a three person board of revisors—that are being used to deny students like myself the right to vote in the general election.

I am a Canadian student who has resided in Quebec for four years. I have moved between apartments, but have not left the province for any substantive amount of time. I have held several jobs in the province and recently had my driver’s licence transferred. Though my family resides in British Columbia, for all intents and purposes, the whole duration of my adult life thus far has been invested in Quebec.

Unfortunately, these qualifications did not satisfy the three-person board of revisors. Yes, I was a Canadian citizen. Yes, I had reached 18 years of age. Yes, I had resided in the province for at least six months. All these facts and their supporting documents were not disputed. Yet, the panel saw fit to pronounce their judgment upon me: I was not enough of a “citizen”; I did not “have the proper profile.”

What is a proper profile? Apparently, it consists of some nebulous combination of Medicare card, driver’s license, tax records, bank account location, and the arbitrary opinion of the three panelists on whether you ‘belong’ to the province. When pressed, the board could not provide a substantive minimum requirement to establish a “profile”—apparently, this concept is so confusing, that each case must be judged separately, rather than by substantive legal criteria. It is worth noting that the most commonly cited piece of documentation that establishes this “profile” is the possession of Régie de l’assurance maladie (RAMQ) Medicare card, which also happens to be explicitly prohibited for out-of-province students.

It also apparently matters which school you attend. On presenting my letter of enrolment, the three panelists gave it one look of haughty disdain, before summarily stating that nine out of 10 students from English universities don’t stay in the province.” While the veracity of this fact is debatable, I am more outraged that the arbitrary opinions of three people, each with their own biases and blind spots, are able to deny me the right to vote in the general election.

This was the summer of 2012 during the registration period for the elections leading to the victory of a minority Parti Québécois (PQ) government. Since then, I have been registered on the provincial voter’s list by virtue of a municipally sanctioned board of revisors’ interpretation of “domicile.” Same application, same qualifications, but different people, and different politics.

As hundreds of other students are documenting the same experience, it is time that we take a stand. While the suppression is primarily gripping students, the bitterness of identity politics that fuels the necessity of these requirements commands all of our attention. The choice of whether we wish to welcome those who are different into our body politic once a reasonable criterion is met is a central question for any democracy.

There are those who would agree that such rigour is required in order to maintain the integrity of a voter’s list comprised of individuals with the intention of staying and investing in Quebec. Even though out-of-province students tend to have whimsical plans about everything from courses to the next meal they might cook, these are not grounds for such obstructionism. Intention is only known by the individual, and is certainly not connoted by how many bureaucratic hoops one is able to jump through.

Even more important are the intentions of the potential governing parties themselves. The right to vote is one derived from the power of the state to affect the life of the individual voter. It is not solely derived, as some have argued, from the contribution of labour, taxation, and the intention to continue to contribute to this province (even though some if not all of these are already demonstrated).

A government that intends to obtain a mandate to shape the very fabric of society in Quebec requires a rigorous election. A party that has declared its intention to regulate the religious garb of public university students cannot be elected by a process that has been repeatedly shown to exclude these students. Wherever we might stand on various political issues, it is imperative that we challenge these unjust electoral practises and interpretations. Our democracy is only as strong as we defend it, and we have no business promoting these values abroad unless we properly govern our own.

Fact Check: The Charter of Values, as xenophobic and outrageous as it is, would not “regulate the religious garb of public university students” as it only applies to public employees

As the Charter stands right now what you say is true. But the Charter is being campaigned to expand beyond public employees and include students at public universities: http://fullcomment.nationalpost.com/2014/03/19/graeme-hamilton-pq-ups-the-values-charter-ante-as-students-would-face-burka-ban/

This is what makes what’s going on even more outrageous.

Hello!

My question is the following; can you vote in British Columbia ? If so, you simply cannot vote “reside” in these two places simultaneously. As much as I shouldn’t be allowed to vote in British Columbia if I am a Quebec resident, you should not be able to vote in Quebec if you are a resident from British Columbia.

The requirements for BC elections are almost the same: 18 years of age, Canadian citizen, LIVING in BC for last 6 months. Technically speaking this means I would be ineligible to vote in BC.

Even if I were able to vote in BC, this line of argument isn’t foolproof. There are plenty of instances where cross jurisdictional voting is allowed. Dual citizens of Canada and the US are entitled to vote for either elections. As long as I can demonstrate I have had a stake in this province, there should be no reason why I can’t participate in these elections (i.e. living here for the last 6 months).

dd dd