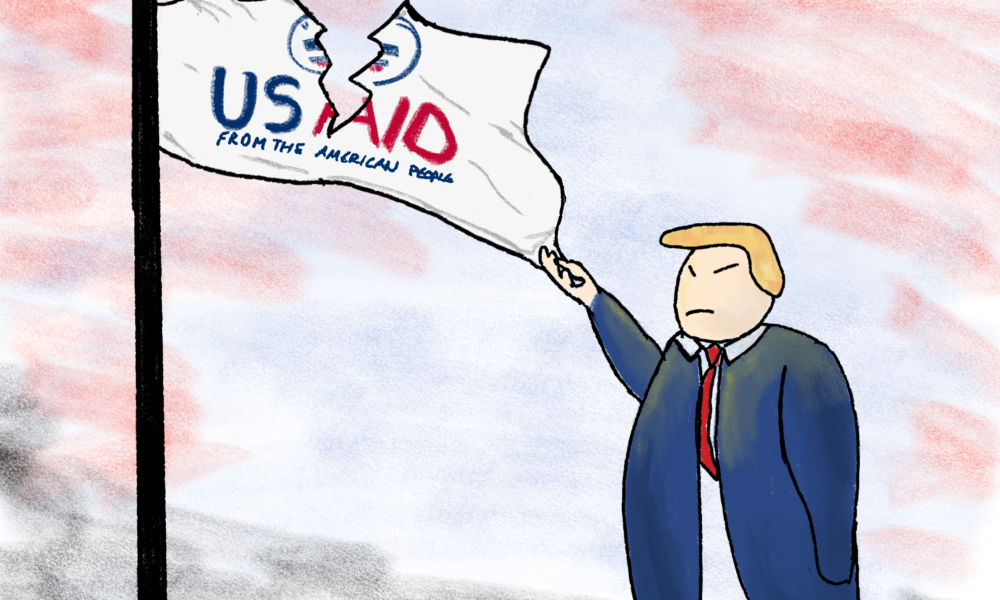

U.S. President Donald Trump’s recent order to defund the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) will undoubtedly have negative global reverberations. One hundred seventy-seven countries currently receive crucial foreign aid from the U.S., of which roughly three-fifths is distributed by USAID. This aid has been a lifeline for impoverished and war-torn regions since the agency’s founding almost 64 years ago. Haiti, for example, benefited from aid delivered in the wake of catastrophic earthquakes in 2010. But this aid was delivered through a highly flawed agency in need of dire reform. In light of this, European countries have an opportunity both to expand their aid networks to make up for lost U.S. funding and learn from USAID’s flaws. By reckoning with a new reality in which the global community can work constructively and collaboratively to undo injustice, the loss of U.S. funding can be turned into a force for good.

USAID was an important symbol within the global capitalist system, demonstrating that the U.S. could turn its highly privileged financial position into a meaningful force for good not only for Americans but for the broader human race. The program showed that affluent countries have a duty to fight against injustices globally, be they environmental or man-made. Indeed, countries like the U.S. and Canada which have benefited hugely from oppressive, violent, and generationally damaging practices such as enslavement and the genocidal killings of and ongoing policies against Indigenous peoples, have a particular duty to do so.

It is within such a history of oppression, especially by western countries, that global aid programs should be understood. They have the power to re-distribute wealth and prosperity to those who have been robbed of it, and this is why the global community must react with decisiveness to make up for the loss in U.S. funding and extend programs where possible. Considering their history of benefiting economically due to the oppression of other nations, developed nations have a particular obligation and capacity to bring about meaningful change, especially in the sphere of climate adaptation which has been largely ignored by USAID.

Importantly, and most unfairly, the countries most affected by climate change are those who have historically contributed the fewest emissions. Europe has contributed 22 per cent of global cumulative emissions, giving it a strong imperative to help smaller, less developed countries adapt to and thrive in a changing earth system. Additionally, eco-racism has soared in recent decades with developed countries bringing about widespread ecological damage in the developing world. Ghana, for example, has become the dumping ground for the fast fashion industry, causing massive water pollution.

To address these issues, European nations can learn from the slew of serious issues with USAID that actually damaged long-term prospects for recipient countries. For one, despite a range of critically important investments, aid is often delivered with only short-term immediate economic growth in mind. Some of the U.S. government’s aid to Haiti, for example, supported low-wage garment factories instead of the kinds of sustainable agriculture that would help make the country self-sufficient and less reliant on food imports.

Perhaps more importantly, the question of who receives aid is a highly contentious one. Billions of dollars of USAID funding have been funnelled towards countries with pro-U.S. authoritarian governments. This is not to say that people should be punished for the actions of their unelected governments, but understanding why and how aid is distributed to some regions more than others is crucial to understanding how aid agencies can work more equitably in the future. Trump’s recent push to sign a $500 billion USD ($721 billion CAD) minerals deal with Ukraine in return for a peace deal is a dangerous message that U.S. support always comes at a price. Modern aid agencies must use these failures as a blueprint for what not to do.

This is not to say that USAID should not exist. It should, and the decision to remove it will ruin the lives of many. To counter its loss, the rest of the world, and Europe in particular, must act boldly by restructuring and increasing funding for aid agencies to ensure that historic ills delivered on developing countries do not go unaddressed. Their impacts are being felt to this day and will continue to do so unless dramatic changes are made.