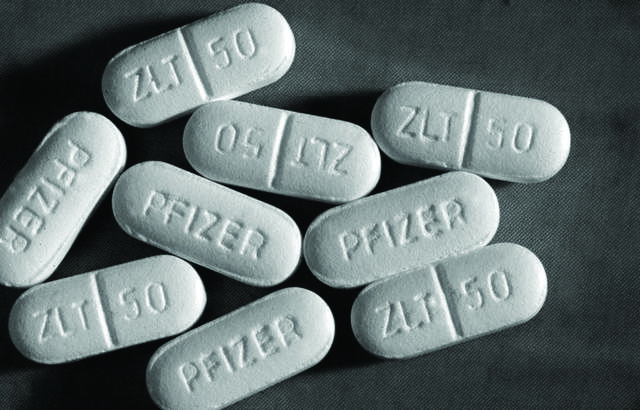

Pfizer, the world’s largest pharmaceutical manufacturer in terms of revenue, is being sued by a woman who claims that the antidepressant drug Zoloft is no more effective than a placebo pill. The plaintiff, Laura Plumlee, alleges that Zoloft failed to alleviate her depression in spite of a three-year treatment course.

Pfizer responded by saying the lawsuit was frivolous. Dr. Jeffrey Lieberman, president of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), agreed.

“As a class, antidepressant medications are highly effective. They alleviate substantial amounts, if not complete symptoms in 50 to as high as 80 per cent of patients treated who suffer from major depression,” he said in a statement to the Washington Post.

However, Plumlee’s claims have firm scientific grounding. A series of analyses spearheaded by Associate Director of the Program in Placebo Studies at Harvard Medical School Dr. Irving Kirsch, have cast serious doubts on Zoloft’s efficacy. Kirsch’s research claims that Pfizer released the medication with full knowledge that it is no better than a placebo for treating mild to moderate depression.

In addition to examining all openly available data on Zoloft’s efficacy, Kirsch requested Pfizer’s unpublished data through the Freedom of Information Act. He discovered that, while the company had supplied two studies showing Zoloft’s superiority over placebo, as per requirements of the Food & Drug Administration (FDA), it failed to publicize the majority of its research, much of which suggested Zoloft’s inefficacy. After taking into account the publication bias—the tendency for significant findings to reach academic journals while non-significant results (those that do not support the research) remain unpublished—into account, Kirsch found that 75 per cent of Zoloft’s effect vanished.

Worse yet, Kirsch believes that much of the remaining effect stemmed from poor study execution. Successful clinical trials are supposed to keep both the clinicians and the patients in the dark regarding who receives the placebo and the real treatment, through a process referred to as a “double-blind trial.” If certain patients discover that they are consuming the treatment, their expectancies regarding its effects may influence their response; Kirsch suspects this is what occurred in Pfizer’s case.

The lawsuit, which was filed in California, asked a California judge to approve two class-action lawsuits—one for California residents, and one United States-wide. It asks Pfizer to reimburse patients for drug costs, and to cease making claims of the drug’s efficacy. While drug companies frequently face lawsuits from doctors and clients, this may be the first instance of a lawsuit demanding reimbursement due to an ineffective drug. The case may face dismissal, however, because of a previous Supreme Court decision stating that an individual may not recover damages they incurred by alleging a drug manufacturer elicited FDA approval for their drug through fraudulent means.

The case may also have important implications for medicine in Canada. While the brunt of prescription occurs in the U.S., recent survey data suggests that Canadian psychiatrists are six times more likely to prescribe sub-therapeutic doses of antidepressants than non-psychiatrist physicians, thereby harnessing the placebo effect.

The lawsuit brings to light a recurring question of accountability in the drug industry. While pharmaceutical companies marketed Zoloft heavily, with very positive-ads targeting consumers, the company failed to publish all of their findings and, as a result, lacks transparency.

Full disclosure: the author is a graduate student whose research dealt with placebo effects.