Lena Faust, a Ph.D. student in epidemiology at McGill, first became interested in tuberculosis (TB) while learning about another disease: COVID-19. What caught her attention, however, were not the diseases themselves, but the difference in global response to each.

“With COVID-19, we quickly developed lots of different vaccines that are highly effective,” Faust said in an interview with The Tribune. “[In contrast,] we have had one vaccine [for TB] that was rolled out one hundred years ago, and it’s not widely used or effective. COVID-19 has shown us that if we want to develop vaccines within a couple years, we can.”

So what accounts for this stark difference in global response? In their study in The Lancet, “Improving measurement of tuberculosis care cascades to enhance people-centred care”, Faust and her team hypothesized that one factor is the insufficient use of care cascades. These measure the number of patients reaching different milestones in care, such as getting tested and completing the first round of treatment for a disease.

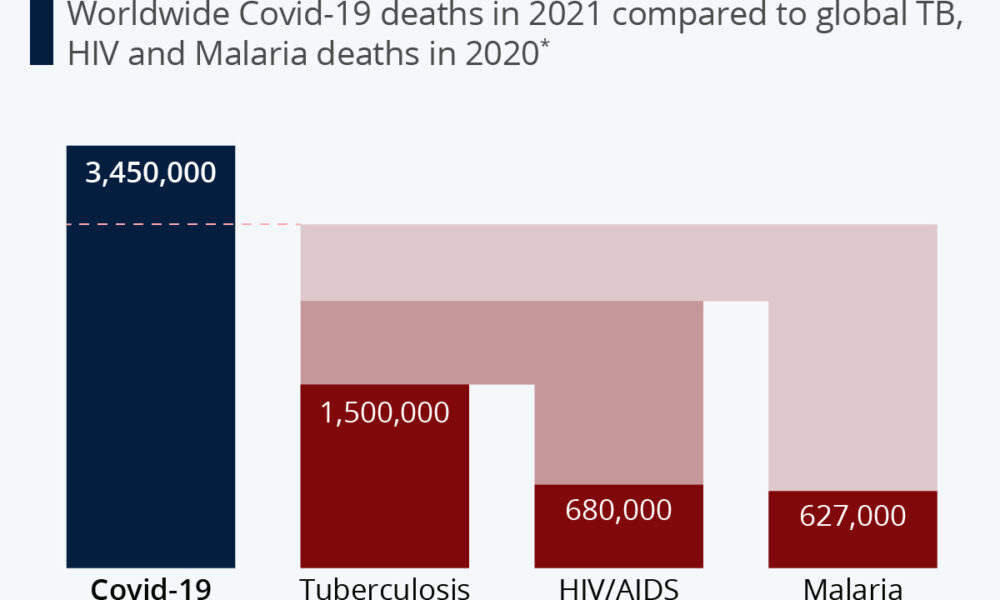

As Faust puts it, TB is often dismissed as a ‘disease of the past,’ even though it is currently the world’s deadliest infectious disease. In contrast, the emergence of the pandemic in 2020 highlighted COVID-19 as a new and frightening disease, leading to the development and approval of three different types of mRNA vaccines in less than a year. However, COVID-19 is not the only disease that has historically garnered a comparatively prompt response.

“The HIV movement has been really exemplary in the way that it’s been able to galvanize support for a cause and resources. Advocacy in the TB world has not been quite as loud,” Faust explained.

She hypothesizes that HIV’s novel appearance in the ‘70s and ‘80s and the ensuing epidemic created a sense of urgency, similar to COVID-19—an urgency that is absent with TB. However, all three diseases call attention to disproportionate medical treatment—affecting, most notably, queer and trans people and Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people in the Americas.

Analysis of care cascades has been a key factor in the global response against HIV. As advocacy tools, care cascades have greatly impacted public health beyond simply modelling data. Faust and her peers argue that the framework is also useful for TB treatment, primarily for identifying barriers in public health services. For instance, some patients live too far from the nearest treatment centres, while others cannot afford to take time off work or pay for childcare while seeking treatment.

“TB treatment is a time-consuming and costly process,” Faust said.

Care cascades, however, can provide guidance to mitigate some of these barriers. For instance, by examining the distribution of a population’s infected regions using care cascades, more funding can be allocated to the construction of health centres in underserved areas. However, while they are an extremely useful diagnostic tool, care cascades are only part of the solution.

“One of the limitations of the cascades is even if you do identify [healthcare] gaps, you also need to understand from the patient perspective what is leading to those gaps,” Faust said. “Care cascades [therefore] need to be used to enhance people-centred care, […] that takes into account the challenges that people face when trying to access [health services].”

As with the global response to COVID-19 and HIV/AIDS, the treatment of TB is marked by drastic inequalities across countries and healthcare systems in terms of which patients receive care and which treatment methods are prioritized. While this is an ever-present issue in global health, Faust proposes that care cascades are one key tool to rectify treatment disparities.

“TB elimination is really a health equity issue. One of the ways to get investment and political support, and also to guide that investment, is to emphasize the role of care cascades in identifying gaps in the care for TB,” Faust said.

Above all, Faust wants the general population to realize that TB is not a ‘disease of the past,’ a way of thinking that can lead to even the deadliest of diseases being overlooked.