Asbestos: Mid-twentieth century American houses were hopeless without it. Malcolm in the Middle made a punchline out of it in an episode. Now, buildings are being forced to remove it, and some countries—including Canada—are introducing legislation to ban it completely. This is a problem that hits close to home, since many of McGill’s historical buildings contain large quantities of the material.

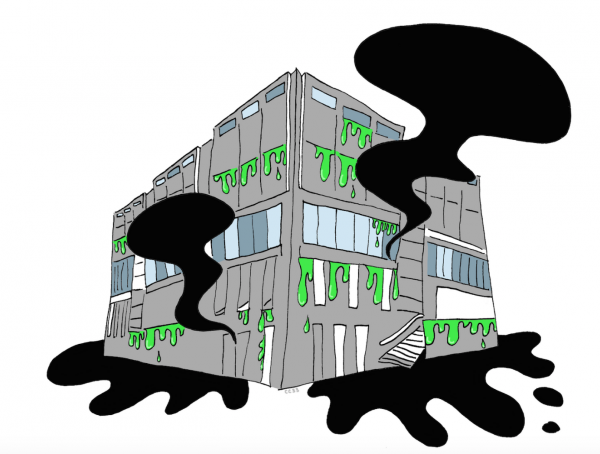

The Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU) building is currently under construction in part to remove asbestos. As the building is over half a century old, it was constructed when asbestos usage was at its peak. Its closure calls the threat of asbestos in other aging McGill buildings into question. The McGill Asbestos Web Database shows that many buildings on campus—including the Adams Building and Redpath Library—have areas where asbestos material content ranges from 25 to 75 per cent. Moreover, many of the reports have not been updated in nearly a decade.

Asbestos refers not to a single thing, but to a category of materials. The word ‘asbestos’ comes from Greek and means ‘unquenchable.’ By definition, asbestos is a group of naturally occurring, fibrous, silicate materials and acts as a very good insulator.

The most common form of asbestos is chrysotile, or white asbestos. In comparison to other variants, it has softer fibres, meaning that it is less dangerous to inhale as opposed to sharp fibres, which get caught more easily in the lungs. Other types of asbestos include tremolite and brown asbestos, although they are not frequently used in commercial products. Asbestos is resitant to fire, electricity, and corrosion, making it useful as a heat-resistor and as friction control in brake linings and household insulation. Asbestos can also act in conjunction with materials such as steel or rubber to strengthen them.

The U.S. government recognizes six types of asbestos, which it categorizes into two main groups: Serpentine, which corresponds to white asbestos, and amphibole, which includes all five other recognized types. Research shows that there are more than five types amphibole asbestoses which the U.S. government does not recognize, but that exist in sizeable quantities and that can be just as toxic.

When it first came into use in the mid 20th century, asbestos was primarily used as a construction material. By the 1980s, it was used as the main fireproofing and insulating material for multi-story buildings. It was incorporated into adhesives, sealants, cement sheets, and was sprayed on walls, ceilings, and girders. Asbestos was truly the ‘miracle material’ of the construction world.

In Canada, asbestos mines constituted a large source of income. By 1966, Canada was producing over 40 per cent of the world’s white asbestos.

While it may once have been an architectural and financial miracle, asbestos has a toxic legacy. When it breaks down, fibres release into the air. These fibres pose respiratory and long-term risks not only to residents in the building, but also workers and repairmen. Tearing down an asbestos-filled building only increases the risk of releasing harmful fibres.

One of asbestos’ most lethal effects is mesothelioma, a form of cancer caused almost exclusively by long-term exposure to asbestos. The disease has a poor prognosis rate; most patients die within 21 months of diagnosis. Canada has some of the highest rates of mesothelioma in the world and asbestos is the number one cause of occupational death in the country. Yet, its use is still increasing worldwide.

Despite the existence of safe alternative materials and the health complications it causes, the desire to ban asbestos has been sluggish. In the U.S., asbestos can still be used in most materials, so long as it is in concentrations of less than one per cent. In China and India, asbestos is still regularly used in building materials.

Canada has only recently taken its first step to banning asbestos. Though the Canadian government lists it as a toxic substance, the legislation to ban it was only introduced for the first time in January of this year and still has a long way to go before implementation.