The Dent Lab in the Stewart Biology building is humming with activity. Run by Dr. Joseph Dent, an associate professor and researcher at McGill University, the lab focuses on the molecular genetics of the behaviour in C. elegans, a nematode roundworm.

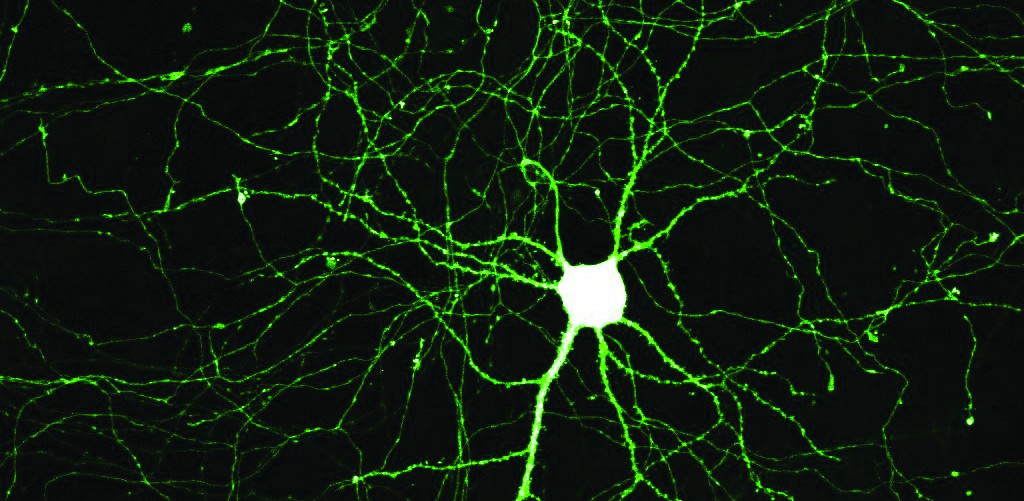

Specifically, the lab’s research focuses on understanding the structure and function of neurotransmitter receptors, the role they play in behaviour, and how we can manipulate them to treat diseases, or better understand how nervous systems work. Essentially, neurotransmitter receptors are membrane receptors that receive electrical signals, facilitating the transmission of information from the brain to the body, and vice versa.

“Our lab has basically two components,” explains Dent. “One is a relatively applied component, and the other a more basic research component.”

The applied component of the lab concerns the relationship between neurotransmitter receptors—important targets for antiparasitic drugs—and pesticides. Dent and his team are currently looking into how existing drugs kill parasites, specifically nematode roundworm parasites, and how nematode parasites develop mutations that allow them to become resistant to these drugs. They hope, through this research, to learn how we can use antiparasitic drugs to better prevent the disease from reoccurring, as well as to make the drugs more effective against resistance developed by parasites.

Nematode roundworm parasites are of significant importance due to the disease caused by the nematode Onchocerca volvulus. River blindness, caused by O. volvulus, is endemic to Sub-Saharan Africa, where 18 million people are at risk of losing their sight. The disease is currently being treated with the drug Ivermectin, which is given in yearly doses by the World Health Organization (WHO) to help people who are already affected and reduce the rate of transmission.

This second area of research comprises the lab’s more basic research aspect. The team has investigated the role neurotransmitters play in behaviour, how the nervous system uses them to modulate behaviour in interesting ways, and the fundamental features of the neurotransmitters themselves. Through this work, they are able to look at the mechanisms behind Ivermectin resistance and how nematodes develop resistance to the drug.

The team works with the roundworm C. elegans in its experiments. While not parasitic, this organism is a much more efficient model to use during experimentation. Since C. elegans is highly similar to other organisms, the team can translate what they learn to various other systems.

“It turns out nematodes have a lot of receptors that humans do not have. These are a good target for anti-parasitic drugs. You want a drug that targets the parasite and not humans,” says Dent.

The Dent Lab works with C. elegans first, and then collaborates with the Institute of Parasitology in order to transfer the work performed on C. elegans to see if it has a similar effect on the parasite.

Looking to the future, Dent says, “We’d love to come up with a new, effective, safe drug that would allow us to have an impact on these diseases.”

“We would also like to better understand the design of the neurotransmitters in all organisms, [in order to] use the information to better focus or target our search for drugs to specific subsets of channels,” explains Dent. “If we understand it, can we design better drugs and better drug targets that are less likely to develop resistance? If we understand how resistance occurs before it occurs, can we use the drugs in better ways?”

Behind the scenes of the lab’s operations, funding plays an important role. According to Dent, the Lab does not get as much support as he would like, since the Canadian health agencies are focused on research concerned more directly with Canadian health. However, the lab receives more support from the agricultural and pharmaceutical industry, which is interested in these drugs because they can also be used to treat livestock. Ivermectin, for instance, is an active ingredient in drugs used by farmers to treat livestock with deworming agents.

“The economics are such that the companies make their money selling these drugs to farmers to treat livestock, so that they can produce cheap meat. We benefit from that, in the sense that we receive industry money to support this research.”

Most important, however, is the idea that spurred this research. When asked, Dent explains it was “just lucky.” While studying the eating behaviour of C. elegans as a post doctoral fellow, Dent discovered a mutant gene that affected their behaviour, and made it less efficient. He located and cloned the gene, only to discover it was a neurotransmitter receptor and the target of the drug Ivermectin—from there, his research took off.

“It often happens that you study one thing and make a completely unexpected observation. What is exciting about research is that, you never know where it will go next—the most exciting research is the research you didn’t anticipate on doing.”