As a student, being able to immerse myself in Montreal’s rich network of museums—without having to pay anything—is an exciting proposition. On May 24, when the Board of Montreal Museum Directors hosted the 29th edition of La Journée Des Musées, Montréalais: Montreal Museums Day, I had to participate.

The Biodôme, one of the participating museums, where living creatures are affected by these masses of people shouting and shuffling through its enclosures, should rethink its participation in Museum Day. The Biodôme’s main selling point is its lack of large fencing separating people and animals. Unfortunately, this absence of barriers creates a shared ecosystem consisting of dozens of screaming children and shuffling adults, not the proper ecosystem for any wild animal.

According to Liberation BC—an animal rights group based in Vancouver—wild animals in stressful situations will often start “chewing, licking, and self-mutilation, as well as rocking, swaying, pacing in regimented circles, head-tossing and neck-stretching, and air-biting.” On such a crowded day, the animals were stressed and retreated into the hidden spaces of their enclosures resulting in a cycle of frustrated children and adults pounding on glass enclosures, screaming, crying, and even shaking trees, all in the hope of seeing interesting and exciting animals. Throughout these fits, no staff, trainers, or security were available to put an end to the deplorable behaviour of their guests—and this was upsetting, to say the least.

The ethics of keeping wild animals in captivity has already been fiercely debated. Museum Day highlighted that while better than a standard cage, the Biodôme’s enclosures were far from ideal for the animals.

''No matter how good the cage is, you can't recreate the wild—it can't be even a pale shadow of the natural environment, with the same species of prey and predators,'' said Eric Pianka, a zoologist at the University of Texas, to the New York Times. ''An animal in a zoo is totally out of context, like a word without the rest of its sentence.''

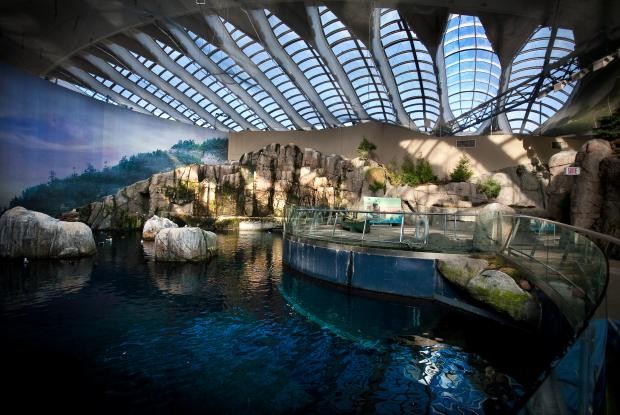

While wildlife conservationists encourage the shift from cages to more natural habitats, the Biodome is too small to host the animals it contains. Originally a 1,620 m2 velodrome used for cycling events during the 1976 Olympic Games, it was refurbished and made into a zoo afterwards. One of its larger inhabitants, the Canadian Lynx, will roam up to five kilometers a day and have territories upward of 50 km2 in the wild. If the Biodome were to give just one of its 4,500 animals a proper habitat the Lynx would need free reign of the entire centre. The Biodôme’s four other exhibits offered more of the same. The animals were either absent or looked under-stimulated, overweight, and sad—be it Atlantic Puffins from the Labrador Coast or River Otters from the Laurentian Maple Forest. The flux of visitors for Museum Day played a part in my forgettable experience of the Biodôme; however, these high prices, run-down conditions, blasé staff, and droves of strollers and people seem to be common occurrences for the animals throughout the year.

The Montreal Science Centre, my next stop, was host to a startlingly small amount of science. One of its permanent exhibits, Les moulins de l’imagination, is actually nothing but a collection of ‘Do-Nothing Machines,’ similar to Rube Goldberg machines—that is, an over-engineered machine that serves little purpose, designed by an artist named Florence Veilleux.

Their other permanent exhibits include Cargo; a history on the process by which boats dock into Montreal, idTV; an interactive exhibit allowing children to produce a TV show; Clic!; something I can only describe as a glorified playpen, filled with building blocks and toys; and Science 26; an “A is for Animation, B is for Brain-style” interactive exhibit. The exhibits were colourful and eye-catching, and the Centre beautiful, spacious, and elegant. But both the permanent and temporary exhibits offered very little actual scientific information. The main temporary exhibit, Fabrik, allowed children to build cars, bridges, and other engineered creations. On one hand, this definitely encouraged creativity, imagination, and teamwork for the children. On the other hand, their exhibits and this type of environment could easily be recreated at a playground with a box of Legos.

While designing exhibits that could successfully enlighten and educate in a broader sense can be difficult, it’s not impossible. Captivating tools like Tesla coils—that create beautiful electrical bursts by using resonant circuits—could teach important lessons about physics. Fun chemistry projects—like the iodine clock—that uses simple and safe ingredients to create bright and fun chemical reactions, are exciting and informative.

For art history museums, an event like Montreal Museum Day is the perfect opportunity to get to know their exhibits, without having to pay the price. For other types of museums, like the Biodome, where the livelihood of their exhibits—namely, animals—require quiet and calm to thrive, an event like Montreal Museum Day is destructive: It puts unnecessary strain on not only the guests and staff but also the exhibits. The price these animals pay—so that guests don't have to—is ultimately too high for a place like the Biodome to participate in Montreal Museum Day.