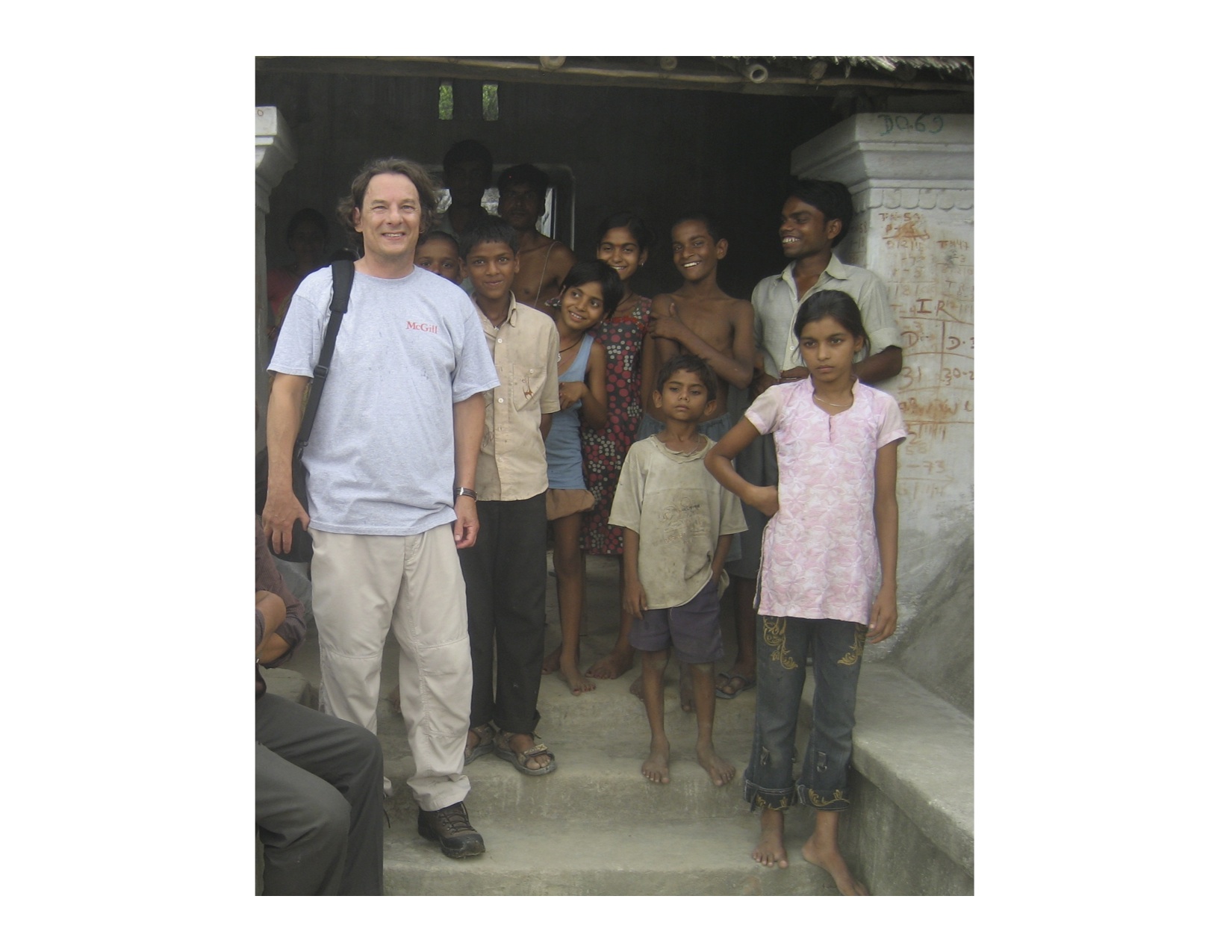

For Greg Matlashewski, a McGill professor and former chair of the department of microbiology and immunology, branching out from the lab and into the field had many positive results for his work regarding treatment for visceral leishmaniasis.

Visceral leishmaniasis, transmitted by sandfly bites, is one of many neglected tropical infectious diseases. Also known as ‘kala azar,’ it is characterized by high fever, substantial weight loss, enlargement of the spleen and liver, as well as anemia. The disease severely compromises the immune system, leaving patients with little resistance to fight off other infections. When left untreated, visceral leishmaniasis is almost always fatal.

There are an estimated 360,000 new cases of visceral leishmaniasis each year worldwide; and 70 per cent of all cases in the world are focused in northern India, Nepal, and Bangladesh. This concentration of visceral leishmaniasis is correlated to the extreme poverty of this area. Poverty has caused malnutrition, rendering locals much more susceptible to the disease. Sandflies, too, are highly common in the area and are attracted to these villages’ mud huts.

Matlashewski’s research on leishmaniasis was originally focused in the lab; however, he wanted to see to it that his work was both relevant, and had an impact on people’s quality of life . “Tens of thousands of people are dying from the disease,” he said, “and yet, there is an excellent treatment for it.”

Working with partners at the World Health Organization (WHO), Matlashewski discovered that although the best available treatments for visceral leishmaniasis may be present at the primary health care centres only several kilometers away in afflicted areas; these are of limited value if people with visceral leishmaniasis remain undiagnosed in the villages and uninformed of the available treatments.

“It’s not a matter of cutting edge science, but rather a question of getting into these villages, and identifying and treating the people to bring the case load down….We need to make sure people know about the available drugs.”

In order to address these problems, Matlashewski took a two-year leave of absence to work for the WHO, and lead a leishmaniasis elimination program as part of the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases.

The program focuses on actively finding cases of leishmaniasis in endemic villages through the use of Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs). ASHAs are women who live in the village and are largely responsible for maternal and childhood health. The program works to train these women to identify those with chronic fever and make sure they are diagnosed. Informative posters are also being placed in villages in order to increase community awareness of the disease, its treatment, and the diagnosis available.

Despite a need to improve communication within villages about this disease, the treatment available is very promising. The cure rate for visceral leishmaniasis is over 95 per cent, with a single dose of liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome). What’s more, patients only require a single treatment—there is no need for a course of pills.

According to Matlashewski, eliminating the disease is a feasible target. It is no longer a question of developing or improving treatment, but rather one of improving communication and education.

“One of the largest problems that the program faces is the massive scale of this disease. The pilot project alone consists of up to 500 villages—to deal with the disease would require reaching tens of thousands of villages.”

Nonetheless, the work of the leishmaniasis elimination program has taken many positive steps towards eliminating the disease in the future.

“If we just stay in the laboratory, there is little impact. I wanted to make a difference; it’s as simple as that.”