Content Warning: Mentions of eating disorders

Global eating disorder prevalence nearly doubled between 2000 and 2018. According to data reported by mothers in the Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development, around a third of all children born in Quebec had exhibited overeating behaviours by the age of five. Furthermore, roughly a fifth of preschoolers exhibited what are classified as “picky eating” behaviours.

Eating disorders are conditions characterized by abnormal eating behaviours that adversely affect physical, psychological, and social function. Past research suggests that maladaptive eating habits in childhood, such as overeating and picky eating, might predict the development of eating disorder symptoms later in life, yet the underlying neural mechanisms are unknown.

In a recent study, Linda Booij, a professor in McGill’s Department of Psychiatry, and her team investigated the correlation between brain structure and children’s eating behaviours.

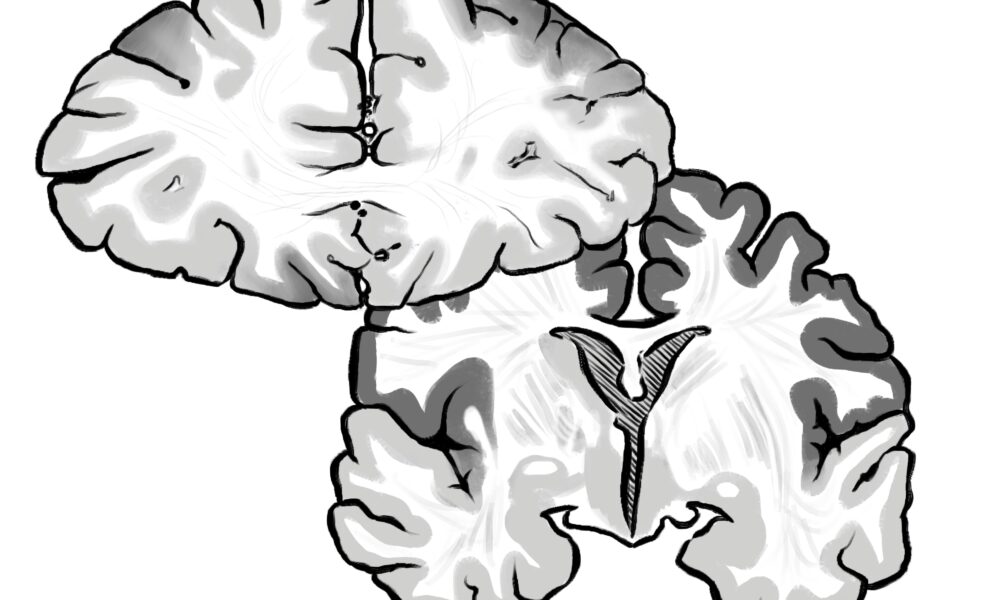

“The goal of the study was to investigate how specific eating patterns in children were linked to their cortical thickness,” Booij said in an interview with The Tribune.

Cortical thickness refers to the thickness of the brain’s outermost layer, the cerebral cortex. Although the cerebral cortex is typically only a few millimetres thick, it makes up approximately half of the brain’s total mass. It contains between 14 and 16 billion nerve cells and carries out essential functions of the brain, including memory, problem-solving, and sensory functions.

Booij’s study focused on two types of eating behaviours: “Picky eating” and “emotional overeating.”

According to Booij, picky eating, in a clinical sense, means consuming a limited amount of food and refusing to eat certain types of food based on their texture, taste, smell, and appearance. In contrast, emotional overeating refers to eating abnormally large amounts of food in response to negative emotions, such as anxiety.

“Overall, children who display picky eating behaviours have a thinner cortex in parts of their parietal cortex, [one of the four major regions in the cerebral cortex],” Booij explained. “We found that the association between cortical thickness and these two eating patterns, [picky eating and emotional overeating], was dependent not only on the sex of the child, but also on the age of the child.”

Booij also highlighted the impact of sex and age on the association between childhood eating behaviours and cortical thickness in the frontal cortex—regions of the brain responsible for the performance of motor tasks, judgment, creativity, and maintaining social etiquette.

“During early childhood, the thickening of certain parts of the frontal cortex was associated with more picky eating. But in adolescence, the association was the opposite to what we saw in early childhood, so teenagers who go on to display picky eating at that age had a thinner cortex,” Booij said. “We did not find any link with sex [in the case of picky eating], so there was no difference in this association between [biological males] and [biological females].”

Conversely, sex has a role to play in the relationship between cortical thickness and overeating.

“For [biological females], more emotional overeating was associated with a thinner cortex in parts of the parietal cortex, and this association showed an opposite pattern in [biological males],” Booij said.

Although the study included both sexes and used a standardized imaging protocol, Booij acknowledged the potential for bias and suggested that future studies could benefit from a larger sample size.

Booij’s research makes a significant contribution to the existing literature on eating disorders. Most studies to date have focused on the link between brain structure and weight or food choices, rather than on eating disorder symptoms across different stages of life.

“Hopefully, this study could help to better understand early risk factors for eating disorders and help to develop ways in preventing eating disorders early,” Booij said. “Our study was done on children and younger teenagers, so it would be interesting to know what happens afterwards. Will these children who exhibit picky eating or emotional overeating behaviours go on and develop eating disorders? This is an important research question for future studies.”

Moving forward, Booij aims to study the impact of eating disorders on brain function and the neural mechanisms that underlie the findings of this study.