In February of 2021, NASA’s Perseverance rover landed on Mars. Perseverance was the fifth rover that the space agency sent to the planet, but it had a unique purpose. The rover conducted the first mission to Mars designed to collect samples to be brought back to Earth, where they would be analyzed for signs of current or past life. With the return mission scheduled to arrive in 2033, questions about potential biological contamination are becoming increasingly urgent.

Anthony Ricciardi, professor of invasion ecology and aquatic ecosystems at McGill, along with an international team of biologists, published an article last year in BioScience outlining a new approach to the issue, which they term “planetary biosecurity.”

Ricciardi is not an astrobiologist or an engineer, but rather a biologist who has studied invasive species and their effects on Earth for the last 30 years. He helped develop a new field called invasion science, which combines several disciplines in order to study, predict, and prevent the impacts of human-carried invasive species.

“The science of invasion biology has guided biosecurity at regional, national, and international scales,” Ricciardi said in an interview with The McGill Tribune. “So my colleagues and I believe that it could similarly guide biosecurity at the planetary or interplanetary scale.”

Invasion biologists are trained to observe organisms taken out of their natural habitats and the destructive impacts this can have on a host ecosystem. Familiar examples of invasive species in Canada include zebra mussels, which remove plankton, an important foundation for aquatic food chains, and buckthorn trees, which are notorious for changing soil conditions to inhibit other plant growth.

Having studied species invasions on Earth, biologists like Ricciardi have learned a number of important lessons and developed principles that Ricciardi believes could be extended to the issue of possible interplanetary contamination.

One of the patterns that invasive species biologists have observed is that isolated ecosystems are especially vulnerable to ecosystem breakdown because the ecosystem has no experience with the invasive species.

“Ecosystems that have evolved in isolation, like Hawaii, or Australia, or Antarctica, are quite sensitive to the effects of introduced non-indigenous species, because they’ve evolved in the absence of similar organisms,” Ricciardi explained. “My colleagues and I would argue that planets and moons should be treated as if they’re insular systems.”

If planets are thought of as isolated systems, then maintaining biosecurity is an even more important issue, and biologists should apply other techniques to protect these ecosystems on Earth.

“For [an] example of how might we do this, a fundamental principle of invasive species management that could be applied to planetary biosecurity is the concept of early detection, rapid response,” Ricciardi said.

Locating and identifying a potentially invasive organism as soon as possible is a challenge on Earth, and an even greater challenge on another planet, where we might not immediately recognize a foreign life form.

Rapid response, on the other hand, is critical to address a possible threat before it becomes entrenched and more difficult to control.

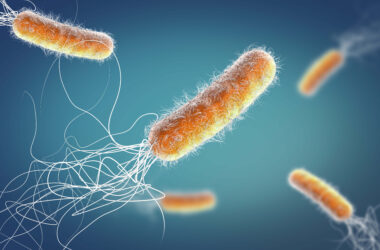

However, any organisms on other planets would probably resemble bacteria or fungi, and there is a very low risk of transmission to Earth.

“The aliens we’re talking about are not little green men,” Ricciardi said.

While the chances of fungal or bacterial contamination are extremely low, Ricciardi says that scientists must take them seriously and prepare for the unexpected.

“We’re talking about things, which are realistic scenarios, but highly improbable. But that’s what low risk disasters are,” Ricciardi said, likening it to a natural disaster such as an earthquake.

For Ricciardi, while these risks are serious, they are also justified by the possibility of new discoveries.

“To any biologist, the search for life beyond Earth has got to be on a list of noble human endeavours,” Ricciardi said. “It could very likely produce an enormous discovery, and I think that could happen in the not-too-distant future. It justifies exploration, but it also justifies caution.”