A timid McGill student observes a group of classmates talking and laughing, and wishes to join them. As she contemplates whether to approach them, she remembers words of encouragement from a therapist: “You will make friends, you are kind and fun. People like you more than you think.” After recalling those reassuring words, she summons the courage to approach the group. Her heart is beating a mile a minute as she stands, shaking, waiting for the group to acknowledge her. To her relief, the group is extremely welcoming. As they let her in on their conversation, she is overwhelmed with happiness, but still fears not being liked.

Many individuals face struggles similar to this timid student. Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is a type of anxiety disorder that causes extreme fear in social settings. Between eight to 13 per cent of Canadians struggle with SAD during their lifetimes and approximately seven per cent of American adults suffer from social anxiety.

SAD is characterized by fear, anxiety, and avoidance behaviours that interfere with one’s daily routine. Individuals with a social phobia have trouble talking to people, forging new social connections, and attending social gatherings because they fear judgment from others.

“I think the fairest way to describe it in my personal experience is feeling a bit like an alien trying not to be found out,” Ashley*, U3 Arts, wrote in an email to The McGill Tribune. “It’s as if everyone around you has some kind of cheat, or instruction manual you were not given, and they are all constantly inspecting you trying to prove that you don’t in fact know what you’re doing.”

This constant fear of being scrutinized by others is accompanied by both physical and psychological symptoms. Physical symptoms include excessive sweating, trembling, difficulty speaking, and rapid heart rate. Individuals also experience emotional and behavioural symptoms such as intense fear of interactions, and may spend time analyzing their social performance for flaws.

According to Helen Costin, a clinician at the Student Wellness Hub, these physical and emotional symptoms result in avoidance behaviours.

“A person with social anxiety may go to great lengths to avoid social interactions and will make choices based on avoiding these interactions,” Costin wrote in an email to the Tribune.

The fear of being judged by others, especially in public settings, can interfere with eating and working habits.

“I also have trouble being comfortable doing anything in front of other people, especially eating in public,” Ashley wrote. “There have been many days I haven’t eaten at school because I was alone.”

Other avoidance behaviours include refraining from dating and asking questions in public.

Symptoms of social anxiety often appear in early adolescence, around the age of 13. According to Dr. Tina Montreuil, an assistant professor in McGill’s Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology, both nature and nurture are responsible for the development of the disorder.

“The incidence of anxiety disorders more generally are associated with a genetic predisposition combined [with] an interplay [of] environmental factors,” Montreuil wrote in an email to the Tribune.

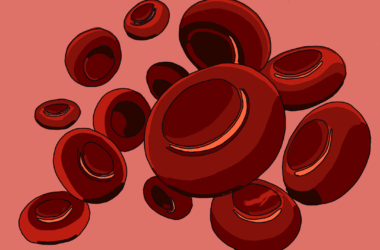

Physiological abnormalities such as imbalances of serotonin, a chemical found in the brain that helps regulate mood, and an overactive amygdala, a brain structure that controls fear and anxiety responses, play key roles in the development of SAD. Moreover, anxiety tends to run in families, further supporting its genetic basis. However, an individual’s upbringing is also a pivotal factor.

“Systemic factors such as overly controlling parenting, greater criticism potentially stemming from inadequate parental support, lack of adequate coping skills, and poor sense of personal competence are all associated with a greater incidence of anxiety,” Montreuil wrote. “In some cases, exposure to violence, trauma, or bullying could be [a] trigger of social anxiety.”

Given that SAD has causes and symptoms that are both psychological and biological, psychotherapy and medication are both effective treatments.

Cognitive behavioural therapy, exposure therapy, and group therapy have all been shown to ease symptoms. Cognitive behavioural therapy teaches individuals how to control anxiety through relaxation and breathing exercises, and also how to replace negative thoughts with positive ones. Exposure therapy helps make individuals more comfortable in anxiety-triggering situations by gradually introducing them to social situations. In group therapy, individuals acquire social skills and techniques to interact with other people. Therapists try to provide a safe, non-judgmental environment for patients to practice these skills through role-playing.

Common medications used to treat social anxiety disorder include Paxil, Zoloft, and Effexor XR, which are anti-anxiety medications as well as antidepressants. However, caution must be exercised with medications: Common side effects include insomnia, weight gain, and upset stomach.

The pandemic has only increased the number of university students struggling with SAD. Extended periods of isolation have both eliminated opportunities for students to exercise social skills and cut them off from the social contacts they feel comfortable with.

“What we’re seeing in the data is that students across Canada and the United States are reporting increasing feelings of loneliness and anxiety—it’s a phenomenon that touches all university campuses, not just McGill,” Dr. Vera Romano, Director of the Student Wellness Hub, wrote in an email to the Tribune.

Students suffering from this disorder encounter many academic barriers in addition to feeling socially stunted. Even routine classroom activities such as presenting in front of the class and interacting with peers become harder, potentially impacting their academic performance.

“It could conceivably make it more difficult for such a student to give a presentation, participate in group work, and if severe enough, attend larger classes,” Teri Philips, Director of the Office for Students with Disabilities (OSD), told the Tribune.

Students with anxiety often make their academic choices around the avoidance of potentially triggering situations.

“Trying to take classes with a larger number of people can make you feel less observed [or] scrutinized,” Ashley wrote. “Trying to take at least one class with a friend also helps if you have questions about the course material and are too scared to ask a TA, [as well as] signing up for a class with little or no participation marks.”

SAD can also impact student life outside the classroom such as when joining student clubs or participating in university events.

“I am the only one out of my friends who has not participated in or joined any university groups, organizations, [or] clubs,” Ashley wrote. “Since I don’t have to interact with anyone, I am unable to practice, and I get stuck in a negative reinforcement cycle.”

Despite their virtual delivery, McGill offers services to help students who are struggling to manage the symptoms of social anxiety. Many of these resources are available through the Student Wellness Hub, which attempts to provide basic mental health services as well as peer support programs to students at both the Macdonald and downtown campuses. However, the Wellness Hub is plagued by long waiting times, lack of staff, and absence of long-term support plans.

Other obstacles also further prevent students from accessing these services. Poor time management, already a stressor for those with anxiety, often results in students prioritizing pressing deadlines, pushing mental health concerns to the wayside. Moreover, 90 per cent of people with SAD often have comorbidities resulting in them suffering from an additional mental illness such as depression or a different anxiety disorder. These compounded symptoms and avoidance behaviours constitute serious obstacles for students in need of support.

The university needs to increase access to mental health services, but professors can also ease the burden on anxious students by improving classroom accommodations.

“I have always appreciated any effort to include anonymity by professors [in class participation],” Ashley wrote. “Simple awareness and recognition by professors would also be helpful, such as having multiple options so students aren’t forced into assignments or positions that will induce an anxiety attack.”

*Name has been changed to preserve anonymity.