Decadent delicacies in food advertisements are not always what they seem to be. In these commercials, motor oil poses as pancake syrup, mashed potatoes become scoops of ice cream, and craft glue replaces milk in a bowl of cereal.

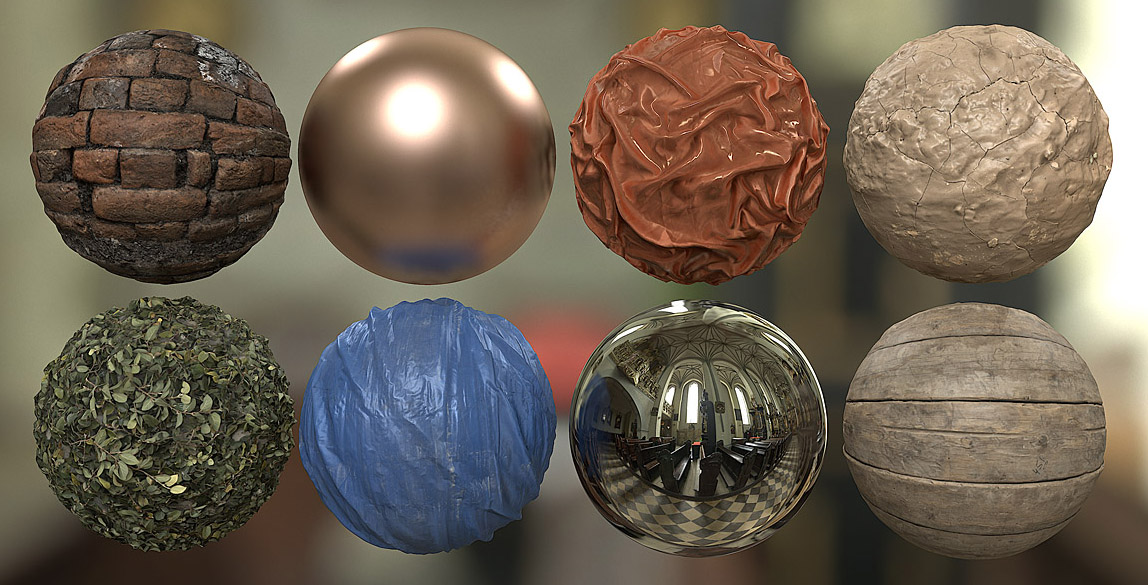

Today, a rendering technique called physically based rendering (PBR) allows advertisers to take further liberties when creating their ads. Rather than cheating customers by passing off one product as another, this rendering technology generates photorealistic images on a computer without relying upon expensive and unwieldy camera equipment. Open any product catalogue today, and it is likely that the images displayed never existed in real life.

PBR relies on physics to generate realistic depictions of objects. According to Derek Nowrouzezahrai, a professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, PBR attempts to create images that portray the physics of light as accurately as possible.

“[PBR] is about getting accurate physical models of the behaviour of light and how it transmits, scatters, reflects, and diffuses for different types of materials,” Nowrouzezahrai said. “Wood versus metal, versus plastic, versus hair, versus skin.”

In general, rendering takes a three-dimensional scene and attempts to output a two-dimensional picture that realistically portrays the original three-dimensional state. In AI and robotics, PBR gives computers sight through an inverse process, where computers input a two-dimensional scene and use it to figure out its three-dimensional surroundings.

“If I have a camera sensor on my car, and I’m taking a 2D picture of my scene, how much of the 3D world can I infer?” Nowrouzezahrai said. “This is the traditional computer vision problem.”

Images created through PBR strive to be as true as possible to real world physics. According to Nowrouzezahrai, this helps robots—especially autonomous vehicles, which take in a lot of natural light—to navigate the real world without incident.

The advertisement industry widely employs PBR technology, since it reduces the cost and time associated with setting up and capturing the ideal shot. PBR also allows directors to be more flexible when designing the scene by freeing them from the restraints of the physical world. As a prominent example, the furniture giant IKEA has entirely adopted PBR technology in the creation of their beautiful catalogues.

“It’s all fake,” Nowrouzezahrai said. “It’s been decades since they have taken a real picture of their product.”

Beyond product advertising and prototyping, PBR is also an integral part of the entertainment industry. In video games and films, PBR produces impressively realistic renderings, even scenes with floating artifacts and fantasy beasts that one would never encounter in real life.

PBR allows us to recreate more of our material world in the digital realm. At the same time, its realistic images also allow robots, born in the binary realm, to find their way into the physical world. Further research and applications for PBR include creating better simulations for humans and robots. For humans, such simulations come in the form of virtual reality experiences. Robots, on the other hand, might use simulations for training purposes before being allowed to operate in the real world.

Through research in PBR and other simulation technologies, visual media artists and machine learning scientists like Nowrouzezahrai have teamed up to find out how much our material world we can recreate realistically in the digital world, and what exactly can be done with the results.