As far as infectious diseases go, Ebola is the new kid on the block. It was first identified in 1976, when two simultaneous outbreaks occurred in Western Africa along the Ebola River; 454 deaths occured that year. In contrast, the World Health Organization (WHO)’s report on the recent 2014 Ebola outbreak states that there have been a total of 3,069 suspected or confirmed cases of Ebola spread across four different countries.

According to WHO, the current Ebola outbreak can be traced back to a single patient—a toddler from a small village in southeastern Guinea, infected in December 2013. By March 24, 2014, the WHO and the Ministry of Health of Guinea declared an Ebola outbreak in four southeastern districts; 86 suspected cases and 59 deaths had been reported.

Kissidougu. Suspected cases (SCs) in Liberia and Sierra Leone. 86 cases, 59 deaths in Guinea.

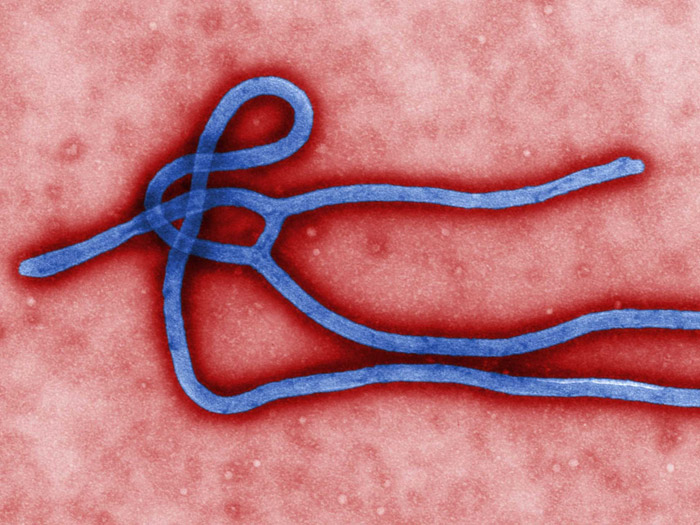

The genus Ebolavirus is comprised of five distinct species: Zaire (EBOV), Reston (RESTV), Sudan (SUDV), Bundibugyo (BDBV), Taï Forest (TAFV), plus one species of Marburgvirus.

Mortality rates for the different strains of Ebolavirus can reach 90 per cent; in contrast, the mortality rate for the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 was a paltry 2.5 per cent. Individuals infected with Ebola virus disease (EVD) often exhibit fever and hemorrhaging. Symptoms vary, but include muscle pain, vomiting, diarrhea, stomach pain, and unexplained bleeding or bruising. Usually, death occurs due to organ failure.

From Guinea, the disease quickly spread to Liberia, with two laboratory-confirmed infections reported as of Apri1, 2014. It continued to gain a foothold in Guinea; by April 17, 109 laboratory cases had been reported. On May 26, the WHO announced the first confirmed case of Ebola in Sierra Leone.

The total number of suspected and confirmed cases ballooned to 1,323 by the end of July. August marked a further rapid rise in infections. Cumulative suspected and confirmed cases surpassed 3,000, and the first confirmed case appeared in Nigeria on Aug. 13.

Luckily, Ebola becomes infectious only after symptoms appear, therefore making transmission difficult. Afflicted individuals are typically too ill to travel and are kept quarantined. Transmission occurs primarily due to unhygienic burial practices and contact with the bodily fluids of infected individuals, typically by family members or healthcare workers. Because fruit bats are suspected to be the Ebolavirus’ primary natural hosts, consumption of bushmeat in affected regions may also be a risk factor.

No specific treatments or vaccines for EVD exist yet. Patients admitted to hospitals are put into intensive care, where treatment focuses on symptoms, not infection. Patients are then treated using oxygen tanks and electrolyte solutions to maintain body salts and blood pressure.

However, a number of promising treatments of EVD are currently being explored. The National Institutes of Health in the U.S., in partnership with a British-based international consortium, recently declared that they would begin phase one trials for a new vaccine against EVD.

In a May 2010 study published in Lancet, macaque monkeys showed 100 per cent survival when exposed to high doses of siRNA (silencing RNA) treatment. This works by using benign RNA strands to ‘kickout’ segments of the Ebolavirus’ deadly genome.

Furthermore, Mapp Biopharmaceuticals Inc. has just released a new product called ZMapp. Using a combination of three monoclonal antibodies to help the immune system fight the Ebolavirus, it acts to induce immunity. The potential treatment is still in it’s experimental stages and has not been subject to randomized clinical trials. Until then, there’s no guarantee of efficacy or safety.

Presently, Canada is at low risk; however, if you’re planning any trips to West Africa, stay safe!