In North America, insects are traditionally seen as pests rather than food. In certain communities in Africa and Southeast Asia, consuming insects for nutritional value is a part of a normal diet. In the western world, there are certainly plenty of candy shops that sell chocolate-covered grasshoppers—mainly as a novelty—but there has not been any real push to bring edible insects into the mainstream western food industry.

In May 2013, the United Nations (UN) Food and Agriculture Organization sought to change this norm by publishing Edible Insects: Future Prospects for Food and Feed Security, a report outlining the benefits of eating insects, especially as a solution to the problem of feeding a growing world population, which the UN predicts will reach 9.7 billion by 2050.

“The concentration of population growth in the poorest countries presents its own set of challenges,” Director of Population Division John Wilmoth explained in an interview with UN News Centre. “[This makes] it more difficult to eradicate poverty and inequality [and] to combat hunger and malnutrition.”

With greater pressure to increase food production, it seems only natural to look for an alternative food source. According to Arnold van Huis, entomologist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands and co-author of an insect cookbook, it takes 1.7 kg of feed for a group of crickets to gain 1 kg of body weight, in comparison to 2.5 kg of feed for a single chicken, 5 kg for a pig, and 10 kg for a cow. Farming insects also creates fewer greenhouse gases, like CO2, and uses less land. With 2,000 species of edible insects containing high levels of protein, iron, calcium, B vitamins, and omega-3 fatty acids, insects have enormous potential as a food source.

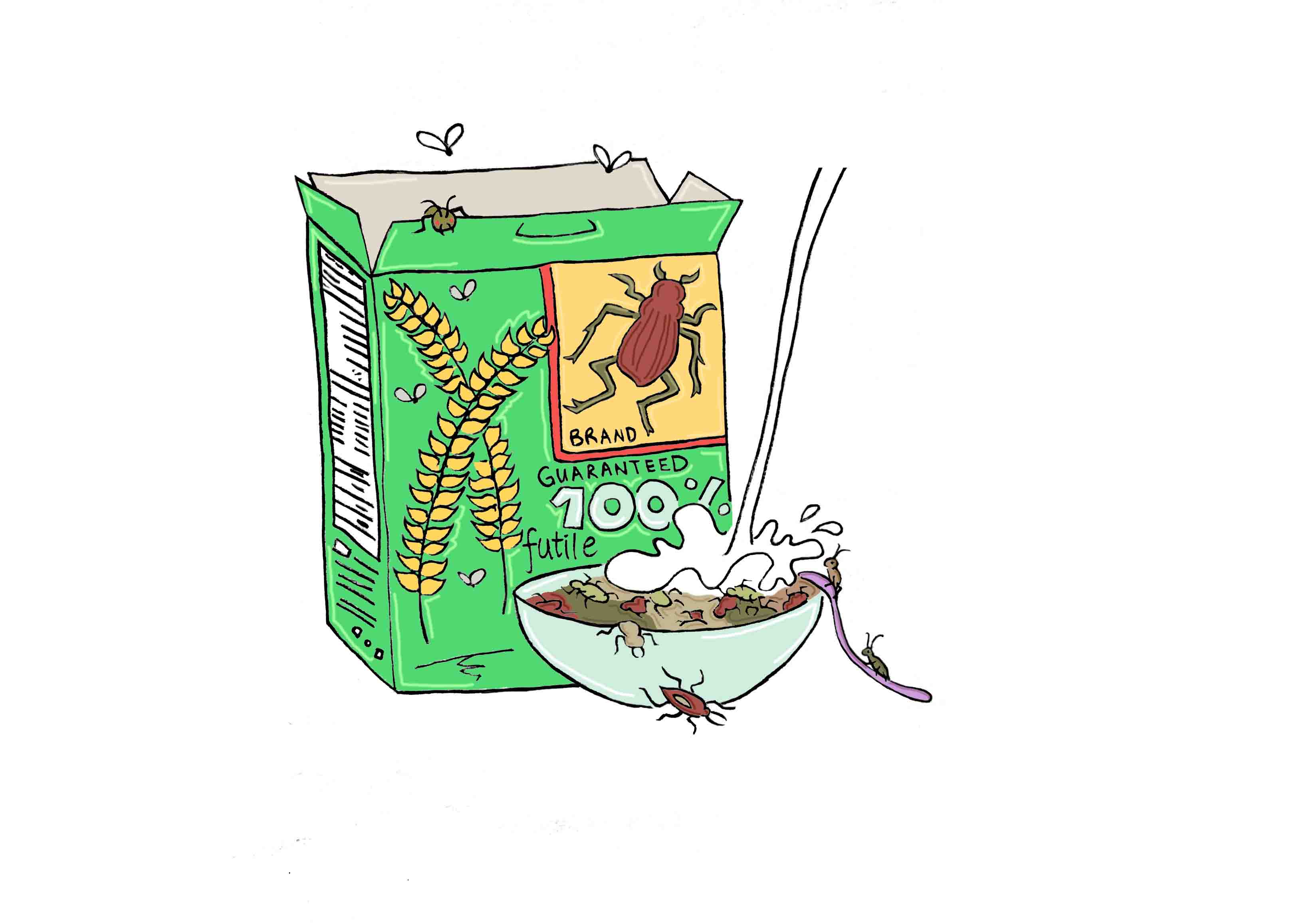

An article published in Psychology & Marketing this past February, looked to address this question by analyzing the psychological and sociological roots of prevailing western perceptions of insects. Indeed, there is a degree of unfamiliarity associated with the practice of eating bugs, often seen as ‘gross’ and ‘creepy.’ Because snacking on insects is thought to be unhygienic and even uncivilized—the latter of which supports the propagation of negative stereotypes—consumers are discouraged from choosing foods that may reflect poorly on their character or social status.

The presentation of the product influences consumer behaviour, so a simple way to circumvent any feelings of discomfort or self-consciousness about entomophagy—the scientific term for eating bugs—is to disguise their appearance to better resemble something closer to western notions of food. Cricket and mealworm flours are available as well, in both powder form for baking and as an ingredient in protein bars.

The case for edible insects continues to be strong, although the challenge in convincing Western consumers to rid any lingering hang-ups they may have about finding fried crickets—which, apparently, have a shrimp-like taste—on their plates remains. With the summer fast approaching, it might be time to throw a mealworm on the barbecue.