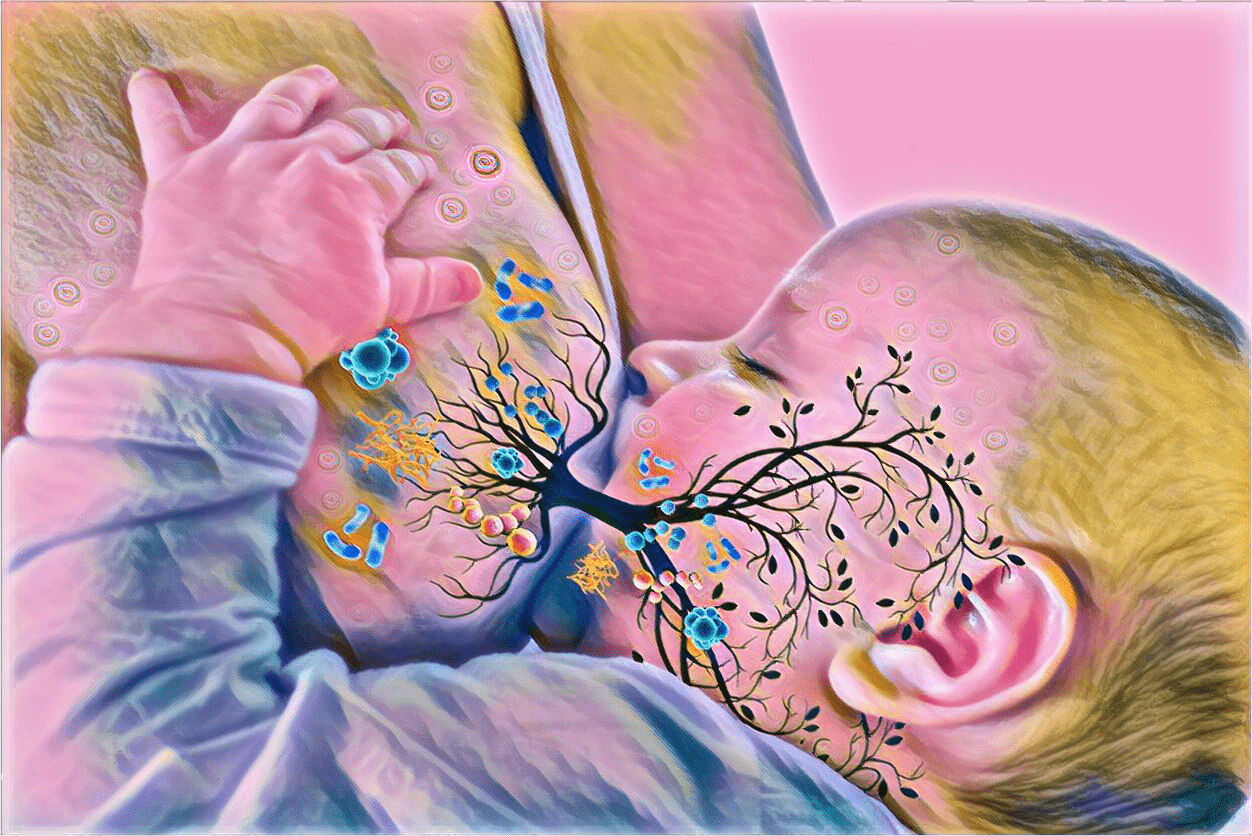

Until recently, scientists presumed that breast milk—the primary source of infant nutrition— was microbe-free. However, recent studies have found that breast milk contains a healthy dose of good bacteria. These microbes originate from the mother’s gut microbiota—the harmless micro-organisms that colonize the human digestive system. The microbiome performs diverse functions like warning the immune system of pathogens, strengthening intestine walls, and regulating metabolism.

Infants, however, are not exposed to bacteria in the womb and only begin to establish their gut microbiota after birth. Breastfeeding is one way infants develop their immune systems.

A new study published in Frontiers in Microbiology by researchers at McGill and the Center for Studies of Sensory Impairment, Aging and Metabolism (CeSSIAM) reported significant differences in the bacterial composition of breast milk when comparing the initial and later months of infant development.

“We observed several common bacteria over both samples of breast milk, but found some more aggressive bacteria in late-stage milk [breast milk at six months],” Dr. Emmanuel Gonzalez, co-author and metagenomic specialist with the McGill Interdisciplinary Initiative in Infection and Immunity (MI4), said in an interview with The McGill Tribune.

Using high-resolution imaging technology, the researchers characterized distinct bacterial colonies found in breast milk. The most common commensal bacterial species found in early milk were Staphylococcus and Streptococcus, which are known to inhabit nasal passages and skin in adults. Sphingobium yanoikuyae, a bacterial species found in late milk stages, is also critical to soil bioremediation and can degrade hydrocarbons like oil and caffeine in the environment.

In their study, the researchers recruited Guatemalan mothers who breastfed for at least six months and evaluated the long-term changes in the bacteria present in their breast milk. They also identified breastfeeding patterns common among low-income countries that are underrepresented in research. Cultural and economic disparities among countries also influence breastfeeding habits: Only four per cent of babies in low- to middle-income countries are never breastfed, compared to 21 per cent of babies in North America.

“When we consistently pick participants from the same environment, we create biases in our results that can prevent us from understanding how much our own ecosystem is having an effect,” Gonzalez said.

The World Health Organization recommends breastfeeding for six months after birth. However, the organization reported that globally, only 41 per cent of mothers adhere to these guidelines, whereas in North America, only 26 per cent of mothers breastfeed long term. This disparity is primarily due to increased maternal employment in North America, where only 10 per cent of full-time working mothers breastfeed for a full six months.

“Our next steps to understand the complexity of breast milk is to look for other types of microbes like fungi, worms, and viruses, which can provide insight into the stability of the microbiome,” Gonzalez said. “In previous studies on pain and its relationship with microbiota, we know that bacteria can sense and react to human hormones, which could be a potential factor that influences these changes.”

While the benefits of breastfeeding are fiercely debated, breast milk does provide high nutritional value for babies, as it contains easily digestible vitamins, proteins, and fats, in addition to healthy bacteria. Immediately after birth, breast milk provides a source of microbial antigens that cause the immune system to produce defensive antibodies. A recent study on maternal microbiota reported that Lactobacillus reuteri, a common probiotic, can prime the most abundant antibody, Immunoglobulin A (IgA), for defence in infant mice. These results suggest that IgA is critical in preventing infections.

Future directions for this research include developing artificial breast milk alternatives supplemented with probiotics to improve infant health.

“Just as billions of humans inhabit this planet, there are several millions of organisms inhabiting their own world [inside of] a human,” Gonzalez said. “A small portion of this world exists within human milk as well, which is shared from one human to another.”