Science fiction has always focussed primarily on imagining the future and coming up with inventions far beyond what was possible at the time. Whether science fiction directly inspired inventors or because writers were able to predict the future, several technologies first featured in fiction are now part of everyday life.

Science fiction first emerged as a genre in the late 19th century as a result of the Industrial Revolution. At the time, many people, including authors, were apprehensive about the rapid innovations of the industrial age and their effect on society.

In an email to The McGill Tribune, Jana Perkins, a recent master’s graduate in the Department of English at McGill, explained the early origins of science fiction.

“There were those for whom these changes were almost beyond comprehension,” Perkins wrote. “And so, at a time when relatively little had been achieved in the way of advanced technology, there was a lot of room for writers to be able to depict the possible futures that could be brought about by either the invention or the widespread adoption of a particular gadget they believed might one day exist.”

Recently, science fiction has pivoted away from discussing new technologies, with an updated goal of analyzing how technology affects society. In questioning technology’s existence, science fiction also asks how current innovations can be better put to use.

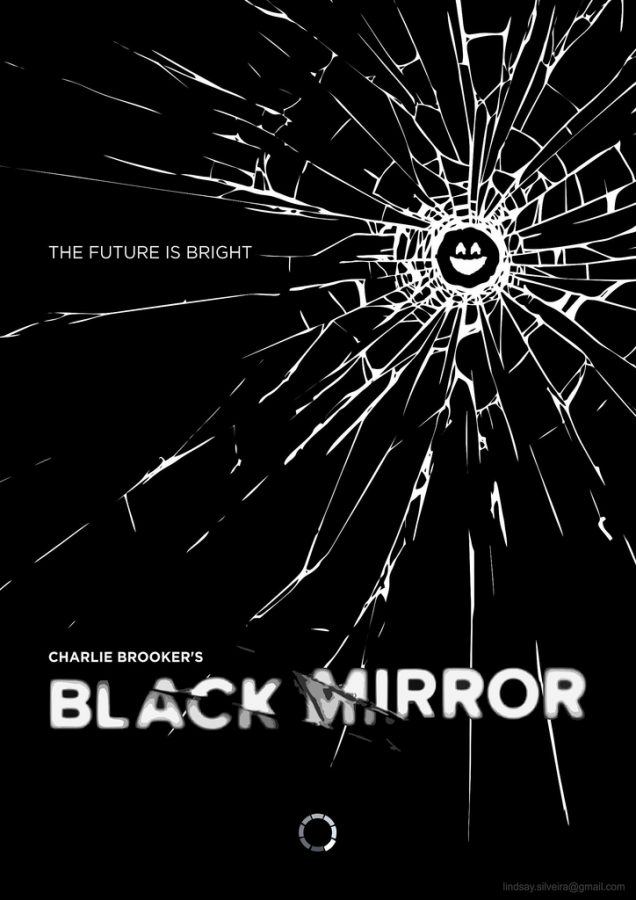

“Take, for example, a show like Black Mirror,” Perkins wrote. “An episode of Black Mirror isn’t seeking to wow audiences by introducing some never-before-imagined technology—it’s inviting viewers to explore the kinds of everyday challenges that would arise from even relatively minor improvements to existing technologies. It’s a shift in focus from the what to the why.”

While the approach of using the impacts of technology on society as a focal point has become increasingly popular, it is most certainly not new. The plots of classic sci-fi shows like Star Trek have largely followed the dynamics of crew members and their interactions with extraterrestrial beings, rather than highlighting futuristic space technology itself.

Another example is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which is often cited as the first science fiction novel and is thought to have inspired organ transplantation. As Dr. George Zogopoulos, assistant professor in McGill’s Department of Surgery, suggested, it is possible that Frankenstein merely reflected the goals of 19th-century medical practice.

“I have not considered the relationship of Mary Shelley’s classic novel with organ transplantation more than a myth,” Zogopoulos wrote in an email to the Tribune. “My impressions have been that representations of transplant and organ donation in popular culture […] reflect myths and societal challenges surrounding organ donation and transplantation.”

It should be noted that Shelley never delved into the scientific details of creating Frankenstein’s monster, leaving many plot holes that later movie adaptations attempted to fill in for themselves.

“Shelley seeks to address such moral questions as whether the ability to imbue inanimate matter with life is a technology that should exist,” Perkins wrote. “And so, for much of the novel, we’re presented with responses to this question from a variety of sources [….] It’s a brilliant narrative structure that expertly invites readers to examine the issue from every angle.”

It appears that fiction has long served to warn scientists about the consequences of technology, especially those in fields that regularly face ethical dilemmas, such as organ transplantation. Many of these warnings are merely a result of misplaced technophobia, inspired by baseless fears that humans could be enslaved by robots, for instance.

While the most terrifying of science fiction’s predictions have yet to materialize, some of their more realistic warnings have come true. A prime example is Gattaca, a 1997 dystopian film that predicted the use of genetic information to assess a person’s status in society. The film’s warnings have proved eerily relevant, with the rise of DNA testing companies and their decision to sell consumer data to insurance companies with malicious intent.

“I wouldn’t say that we necessarily take our cautionary tales from fiction, but fiction does serve to remind us perhaps of our limitations, and this is useful,” Dr. Steven Paraskevas, a transplant surgeon at McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) and assistant professor in McGill’s Department of Surgery, wrote in an email to the Tribune. “Sometimes, I think fiction may remind us of how public perception of what we do can be negative or misunderstanding. Life in a hospital isn’t exactly like it appears in ER or Grey’s Anatomy, but it’s informative to see how [physicians and scientists] are perceived.”

This dignified portrayal of scientists in the media has often inspired people to pursue STEM careers. Unfortunately, science fiction frequently portrays science incorrectly or completely ignores its basic laws in an attempt to stretch the realm of possibility.

“Fictionalized role models inspire people, and may lead young people to see themselves in a certain career,” Paraskevas wrote. “At the same time, I doubt people become disillusioned when things in reality don’t quite happen the way they do in a movie or novel, or worse, the 60-minute time frame of a series episode. The truth is, science and medicine are so much more complex than they are depicted in pop culture, and discovering this complexity is part of the fun.”

Careers in science are also often glamourized in fiction and popular media, omitting details about the gruellingly long hours, failures, or dead ends. This is partly because some science fiction writers have no background in STEM-related fields, along with the fact that the mundane aspects of scientific practice are less interesting to audiences.

The relationship between science and fiction is complex and oftentimes difficult to reconcile. Although science fiction does not foretell the future or directly influence the invention of new technologies, it can be an interesting reflection of society’s dreams and aspirations. Science in literature and film gives authors and audiences a chance to see beyond the current limits of their age and presents an outlet for non-scientists to express their concerns about technology.

In most cases, scientists’ aims do not revolve around the dreams of fiction writers of previous centuries. Rather, they invent because of an inherent curiosity to push the boundaries of science: To discover new and better ways to do the things humans already do, such as communication, travel, and the many jobs that have now been automated.

“I don’t think there is a conscious effort to bring fiction to life, as far as science is concerned,” Paraskevas wrote. “We don’t really develop or invent the worlds depicted in science fiction, so much as validate them [….] If we ever develop huge starships that travel at incredible speeds, it will not be because they were dreamed by 20th-century filmmakers, but rather because of the enduring wish to see what’s out there beyond our world.”

Thank you for a valuable experience, Jana!

I agree (if I understood you correctly): Implicit questions in shows like Black Mirror are like lifeboats to the future.