Faced with the sharp shifts of climate change and continuous human expansion, animals must adapt to survive—an ability that depends largely on a species’ genetic diversity. Professor Ioannis Ragoussis, head of genome sciences at the McGill Genome Centre, is studying this diversity by sequencing the genome of species native to Canada, including the lake trout.

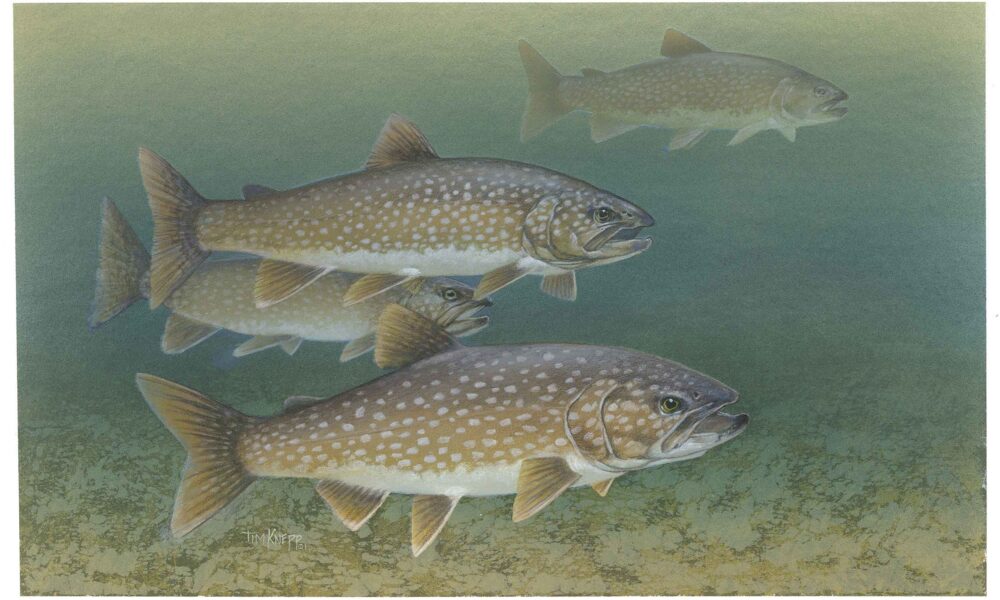

The lake trout is a glacial relic that has commanded a widespread presence in North America since the Wisconsin glaciation event ended 11,000 years ago. Flourishing in deep, cold waters from Alaska to New England, the trout is the top predator of the Great Lakes. Its abundance made it a major food source for many Indigenous communities, from Inuit in Northern Quebec to the First Nations in Yukon.

Throughout the 19th century, overfishing by colonial powers, corporate pollution, and invasive species predation devastated the trout population. By the 1960s, the lake trout population had plummeted in many lakes it had previously thrived in. A significant consequence of this major decrease in population size was a loss of genetic diversity.

“Fish and other organisms try to maintain some form of genetic diversity that will allow them to adapt to different conditions,” Ragoussis said in an interview with The McGill Tribune. “If the genetic diversity is lost, then the ecological diversity is lost at the same time [and] they don’t have the tools to adapt to a changing environment.”

Genetic diversity allows species to adapt to changing conditions, like the increasing global average temperature and ecosystem perturbations caused by climate change. Greater variety within the gene pool is crucial for repopulation and also helps ensure that individuals can survive in many different conditions—if a disaster arises and all the fish are genetically similar, then the population is at greater risk of extinction.

Genome sequencing serves as an essential tool for the many hatcheries working toward lake trout repopulation. A species’ genome can also provide insight into its evolution and serve important strategic purposes.

“Once we establish the required diversity using science, we can make a much better argument to governments and environmental organizations [about] the need for maintaining certain numbers of species,” Ragoussis said. “It will be a tool that will allow us to have a better leverage in establishing environmental protection and conservation efforts in Canada.”

The lake trout genome was sequenced as part of CanSeq150, a collaborative initiative by the Canadian Genomics Enterprise to assemble the genomes of 150 species through a network of Canadian research centres. Following the initial success of this program, the Canadian BioGenome Project seeks to sequence the genomes of 400 species crucial for biodiversity and conservation in conjunction with the Earth BioGenome Project. The work will be shared by McGill Genome Centre, the Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre in Vancouver, and the Centre for Applied Genomics at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

“There are committees that are deciding who will go into Noah’s Ark, but due to the financial pressure, this time it can only include 400 species,” Ragoussis said. “We want to select the ones that are more threatened or very important to Indigenous communities. There is priority given to the needs of Indigenous populations and communities, like the sequencing of the genome of the muskoxen.”

The interdependence of ecosystems places great importance on the survival of each of its members. This project will sequence the genome of species from every level of animal life, from insects and fungi to fish and mammals. Understanding and preserving the genetic diversity of the animal kingdom will be crucial for a future of prosperous and resilient natural environments.