In her novel Light in my darkness Hellen Keller wrote, “There is no better way to thank God for your sight than by giving a helping hand to someone in the dark.”

Robert MacLaren, a surgeon and professor at the University of Oxford, has set out to do just that by using gene therapy to treat certain types of blindness with hopes that, in the future, the technique could be used to effectively combat this impairment.

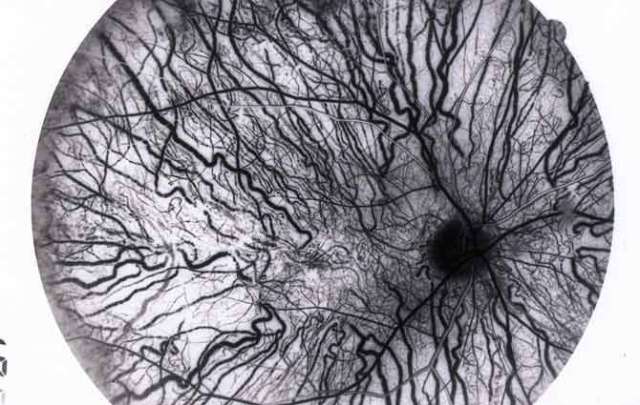

The results for the patients of this experimental gene therapy were published in The Lancet medical journal and have the potential to encourage further research in this area. The trials focused on nine patients who suffered from a particular type of blindness called choroideremia, an inherited disease resulting in progressive blindness. Choroideremia is due to a genetic defect that causes the light-sensitive cells at the back of the eye to degenerate. As these cells die, the retina begins to shrink, leading to the gradual loss of vision.

The therapy involved surgery to inject the missing gene responsible for the choroidermia disease. The gene piggybacked on a virus that acted as a vehicle of delivery, helping the gene navigate right to the retina. Since the initial surgery, the results have been very inspiring—every one of the patients showed an improvement in vision, ranging from higher perception in dim light, to being able to read more lines on the eye chart.

“This [treatment] has huge implications for anyone with a genetic retinal disease such as age-related macular degeneration or retinitis pigmentosa, because it has for the first time shown that gene therapy can be applied safely before the onset of vision loss,” MacLaren said in an interview with the University of Oxford News.

One of the first trials was conducted with a 63-year-old man, Jonathan Wyatt, who at the time of the surgery had very minimal vision. Since undergoing treatment, he has experienced a significant improvement in sight.

“Now when I watch football on TV, if I look at the screen with my left eye alone, it is as if someone has switched on the floodlights,” Wyatt said in an interview with the University of Oxford News. “The green of the pitch is brighter, and the numbers on the shirts are much clearer.”

Another patient, Wayne Thomson, had a similar experience.

“I’ve lived the last 25 years with the certainty that I am going to go blind; and now, [after the operation] there is the possibility that I will hang on to my sight,” he said.

Since choroidermia is a degenerative disease, it may be premature to have very high hopes for the treatment. MacLaren’s paper consists of data for only six months past the surgeries. Therefore, it is still uncertain if the efficacy of the treatment is permanent or transient.

Regardless, MacLaren’s study has sparked optimism among other researchers. Jean Bennett from the University of Pennsylvania applauded these efforts, saying that the technique could be helpful in fighting against other causes of blindness like macular degeneration. However, Bennett is cautious to jump to conclusions.

“We can do as much work as we can in the laboratory and try to sort out all the variables, but there are always surprises,” she said in an interview with ABC News.

The researchers remain optimistic and look forward to the future results of the study.

“I am incredibly excited to see what will happen,” MacLaren said. “The difficult bits are done. We know the virus carrying the gene therapy gets into the cells and the retina recovers after the surgery. Now it’s just waiting to see how the patients progress.”