Indigenous communities all over the world, from the Cree of Waskaganish to the Sámi of Sápmi, differ greatly in language, history, and culture. However different they are from each other, a common belief that informs the traditional practices of many Indigenous Peoples is the interconnectedness of humans, animals, and the Earth. Yet, the colonial infrastructure of industrialization – and the adverse effects it has on Indigenous lands – are endangering the health and cultural practices of Indigenous communities worldwide.

Researchers from the University of Helsinki, in collaboration with the Department of Natural Resource Sciences at McGill, sought to better understand the effects of pollution on the health of Indigenous Peoples. The study draws data from close to 700 research articles, books, and government reports. They found that Indigenous Peoples across the globe are disproportionately affected by the adverse impacts of environmental pollution despite their continued resistance to resource exploitation. These effects include severe health ramifications, such as higher rates of cancer and diabetes, and social repercussions that lead to the deterioration of cultural traditions. These consequences are reinforced by physical changes to their lands.

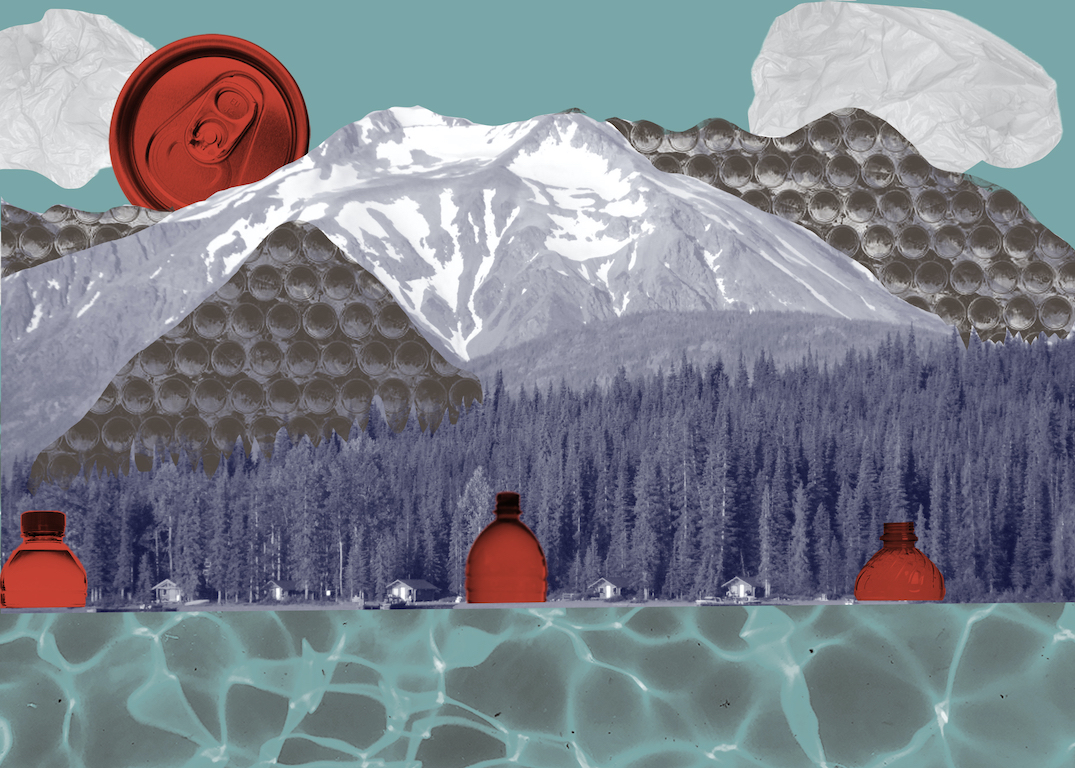

“Sadly, Indigenous lands represent to the global economy some of the remaining frontiers of resource extraction, and because of this, they are often the targets of operations that entail pollution risks,” Álvaro Fernández-Llamazares, lead author of the study and environmental scientist at the University of Helsinki, wrote in an email to The McGill Tribune. “Indigenous Peoples are among the populations at highest risk of impact by environmental pollution of water, land, and biota through both exposure and vulnerability.”

Abandoned mines, oil pipelines, and waste facilities are just some examples of environmental hazards to Indigenous Peoples that are a result of industrial development. In one case, the study found that oil spills from natural gas exploitation in the Peruvian Amazon had seeped into waterways vital to Indigenous Kukama communities, and were linked to an increase in blood mercury levels in children. Mercury poisoning can have toxic effects on the brain, kidneys, reproductive system, and cardiovascular system, and is especially harmful to pregnant women and young children.

Indigenous groups that rely on waterways for sustenance are especially affected by chemical contaminants. Many First Nations’ traditional fishing practices involve consuming all parts of fish, including fatty tissues where heavy metals accumulate. Consequently, river pollution not only presents an increased health risk, but also compromises the safety and longevity of First Nations dietary customs.

The impacts of pollution on Indigenous communities is a contributing factor to a larger human rights crisis, as Indigenous Peoples worldwide defend infringements upon their right to a clean environment. In many First Nations communities across Canada, such as the Neskantaga Ojibwe Nation, the Canadian government has allowed 20-year boil-water advisories to persist despite its obvious health hazards.

Niladru Basu, professor of Natural Resource Sciences at McGill and co-author of the study, advocates for an integrative approach to scientific research and community activism.

“The traditional way that we would study these issues from a Western scientific perspective is to measure exposures and to relate that epidemiologically to health outcomes,” Basu said in an interview with IEAM. “If we […] look at it holistically, there are other important dimensions from the Indigenous perspective concerning social wellbeing and cultural awareness.”

The deep connection between Indigenous Peoples and their traditional lands is sacred and inextricable. Any contamination inflicted upon their physical environment is also detrimental to the spiritual and social health of those communities and traditions. Therefore, the environmental knowledge of Indigenous Peoples must be held in utmost consideration of both scientists and policymakers.

“It is critical to educate and empower Indigenous Peoples and enable them to have their stories heard,” Basu wrote in an email to the Tribune. “As such, policymakers must ensure active and meaningful participation of community members in science-policy efforts.”